Nadesda Hagges, 37, will never forget leaving her home country of El Salvador during the state's brutal civil war. She was only a kid — around seven or eight, she thinks — as she gazed out the airplane window at vast expanses of green hills. El Salvador was all she had ever known. Her father was captured and murdered by government forces in 1981, when Naddy was only one years old, and she lived with her mother and younger siblings.

She remembers marching in the streets against state injustice with her mother, clad in her school uniform, chanting and singing songs about peace and love and liberty. Naddy also remembers the police — how they would come out and stop them, often with violence and nasty threats.

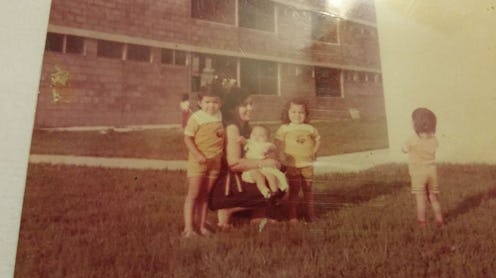

Eventually, Naddy's mother realized that for the sake of her daughters, they couldn't remain in El Salvador. Thanks to the help of a Baptist organization, they fled the war-torn country for Canada.

For Naddy, her family had no choice but to flee when they left El Salvador in 1988, a country ravaged by civil war between 1980 and 1992. She was also lucky. Today, the Northern Triangle — consisting of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala — remains some of the world's most dangerous countries, with El Salvador deemed the murder capital of the world in 2016 due to government corruption and high levels of organized crime among gangs. And, with Trump's stringent anti-immigration policies and promises to build a wall against undocumented immigrants, their odds of escaping violence continue to diminish as refuges are increasingly turned away or deported.

In 2014, tens of thousands of women and unaccompanied children journeyed from Central America to the U.S. to save their lives and seek asylum — an estimated 50,000 people cross into Mexico every year, mainly from this region, with over 68 percent of that population reporting they were victims of violence, according to a MSF report.

I had no idea what was going on, if I was ever going to see her again. I was being happy and smiley for my sisters during the day and then just weeping in bed.

Naddy remembers the threats she faced while in El Salvador in the 1980s. Her mother, who was involved with guerrilla forces, was eventually captured and jailed by the government, and Naddy went to live with her grandmother out in the countryside. She spent hours barefoot roaming the fields, snacking on mangos and oranges and papayas. When she'd return home in the evenings, her grandmother never understood why the young girl wasn't hungry for dinner.

Violence lurked even beyond the cities. Once, she was woken up after a bullet pierced through her grandmother's window. Naddy believes it was a warning to stay away. Her mother was eventually released and placed her daughters in a secluded orphanage for protection. There was little clothing or food and Naddy, around five years old at the time, was terrified. "I had no idea what was going on, if I was ever going to see her again," she recalls in an interview with Bustle. "I was being happy and smiley for my sisters during the day and then just weeping in bed."

El Salvador's civil war officially began in 1980, after years of state terror and the rise of leftist guerrilla movements that denounced state violence and demanded democratic reform. That year, Archbishop Oscar Romero, a beloved pastor and advocate of the poor, officially declared a martyr in 2015, was assassinated by right-wing death squads while delivering mass. In his final sermon, Romero, a vocal critic of state violence, pleaded, "In the name of this suffering people, I ask you, I beg you, I command you in the name of God: stop the repression!"

If someone risks their life to make a dangerous journey, there is a fear based upon reality. So, when the courts deny their asylum application there should be knowledge that some of those people will be killed when they're sent back.

Romero's death triggered over a decade of mass violence. The government and military, supported by the U.S., frequently used death squads, disappearances, and torture against the left. In total, around 75,000 were killed throughout the 12-year conflict, with a 1992 UN Truth Commission determining that over 90 percent of the crimes were committed by state forces. In the war's aftermath, the state passed an amnesty law to prevent prosecution of those responsible for the atrocities, while also denying access to justice or reparations for victims. In July 2016, decades later, El Salvador's Supreme Court finally struck down the amnesty law as unconstitutional.

"I don't think I'll ever come back to this country," Naddy thought as her plane flew into the clouds toward Canada, away from the only home she had ever known.

Between 2010 and 2015, the number of asylum applications from the Northern Triangle increased by 597 percent, according to the UNHCR. Yet, and in 2016, of the 8,519 people who applied for asylum status in the U.S. from the Northern Triangle, only 382 cases were ultimately approved.

"My experience is that most people want to stay in their homes. I've gotten a number of phone calls from people crying because they want to be back home and would be killed if they return," Elizabeth Kennedy, a social scientist at San Diego State University who researches youth and forced migrants and their families from the region, tells Bustle. "If someone risks their life to make a dangerous journey, there is a fear based upon reality. So, when the courts deny their asylum application there should be knowledge that some of those people will be killed when they're sent back."

In 2014, and based on Kennedy's research, she estimates that 83 people deported back to their home countries by the U.S. were ultimately murdered.

"We're repeating history," she explains to Bustle about today's refugee crisis. "With low-income populations, it seems to be that war has been declared on those groups even though they have the least responsibility in the problem. I feel like those who most like Trump say, 'don't think about those consequences because they are outside our borders,' and don't realize it also affects us in the long-run."

For Naddy, who now resides in Sumter, South Carolina with her husband and three children, fleeing was a matter of life or death. "There was a sense of peace that we could actually go to the grocery store without worrying someone was going to rob us or see something really tragic," she says about life in Canada. Thirteen years ago, she moved to South Carolina, where her husband works as a police officer. The breeze outside her bedroom window is calming and she frequently attends church and plays with her kids at the public pool.

"It was a new chance at life. My mother was able to go to school, raise her children in a safe atmosphere, we could go to the pool or the movies. We learned what it was like to have fun and create memories and have the freedom to walk down the streets without fear," she says.

A wall is never sufficient to keep people out when you're fleeing for your life.

In Trump's first 100 days of office, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers detained more than 41,000 undocumented immigrants — a 38 percent year-on-year increase. "When we encounter others who are in the country unlawfully, we will execute our sworn duty and enforce the law," ICE declared in a statement.

Yet, according to a Slate report, fewer than nine percent of the detainees whom ICE considers to be, "criminal aliens," were actually connected to violent crimes. Instead Trump's hardliner immigration policies, from pledging during his campaign to mass deport undocumented immigrants to his January Executive Order to hire thousands of more border patrol agents and build a "contiguous, physical wall or other similarly secure, contiguous, and impassable physical barrier," has targeted the very people often escaping for their lives.

On Trump's pledge to build a border wall, Kennedy acknowledges such a wall does already exist. During President Obama's tenure in office, deportations reached an all-time high, with over 400,000 people deported in 2012. But, they also declined in his last two years, and in 2014 he issued a memorandum to avoid deportations involving people with a status as victim or humanitarian factors like poor health or young children. "A wall is never sufficient to keep people out when you're fleeing for your life," Kennedy says. "Your only alternative is death so you'll do whatever to survive."

Naddy says she is grateful to have grown up in Canada. She escaped the violence of her home — a place of beautiful memories, like running through coffee bean fields and climbing mango trees, but of equally devastating political circumstances that tore her family apart.

"A lot of these people are leaving because there's no other way to live," Naddy says about today's migrant crisis. "I have aunts that still live in El Salvador and cousins, and they are wonderful, good kids trying to go to school and get an education and make a good life for themselves yet are walking to school with their backpacks clutched to their chests because they can get raped."

"There is a real fear going on in my country," she adds.