Books

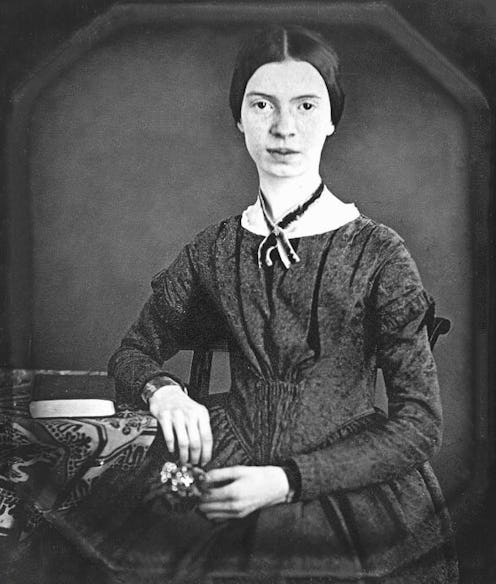

How The Obsession With Emily Dickinson's Virginity Exposes Innate Literary Sexism

She’s been called mysterious and a rebel, dubbed a “virgin recluse” and a “scandalous spinster”, and ranked among literature’s most-noteworthy virgins. She’s also written some of the most striking, passionate, visceral, and erotic poetry in the history of English literature. So what does our obsession with Emily Dickinson’s virginity say about the way we value her — and perhaps all women writers? Especially when it’s practically impossible to find a male writer whose own erotic life (or, lack thereof) bears the same scrutiny?

Admittedly, the details of Dickinson’s life are compelling — if conflicting, depending on who you ask. Scholars tend to divide into two camps: those who believe the narrative of Dickinson as a virgin recluse whose innate talent and imagination led to her erotic poetic passions, and those who believe there was a bit more going on between Ms. Dickinson’s sheets than previously known. Rumors of thwarted engagements, gentleman callers, lesbian love affairs, and lusty love letters abound. Her isolation from the world has been blamed on everything from a dominating, Christian father to Dickinson’s own increasing eccentricities later in life. The significance of her tradition of wearing all-white dress has been questioned. And her writing — over 1800 poems that were rebellious, erotic, blasphemous rants against God, and more — was largely stored in a locked box in her room and only discovered after her death.

Though I discovered the anthologized Dickinson in high school, it wasn’t until a college seminar on Dickinson that I truly began to dive in — and discovered that one of the only things college students have heard about Emily Dickinson is that she was a virgin, and one of first things they want to know is if it’s true. A poem of particular interest, both to new readers and more seasoned Dickinson scholars alike, is Wild Nights! Wild Nights!, noteworthy not only for the verse itself, but for being the poem that gave Dickinson’s posthumous editor pause: “One poem only I dread a little to print — that wonderful 'Wild Nights,' — lest the malignant read into it more than that virgin recluse ever dreamed of putting there,” Colonel Higginson once wrote to his co-editor, while compiling the 1891 edition of Dickinson’s poems.

The controversial poem reads:

"Wild nights! Wild nights!

Were I with thee,

Wild nights should be

Our luxury!

Futile the winds

To a heart in port,

Done with the compass,

Done with the chart.

Rowing in Eden!

Ah! the sea!

Might I but moor

To-night in thee!"

In Lea Bertani Vozar Newman’s book, Emily Dickinson "Virgin Recluse" and Rebel: 36 Poems, Their Backstories, Her Life — the product of seven years of research into the life, times, and writing of Dickinson — Newman uses the author’s own poetry to explore the facts behind the myths. She writes:

"Scholars differ on how much attention we should pay to Dickinson's life when reading her poetry. Some believe it is her interior life and her genius as a poet that is most significant… As the facts clearly reveal, what Emily wanted most in life was to write poetry. To do that, she chose the life of an eccentric and celibate recluse. Relieved of the obligations and distractions that went with marriage, or an active social life, or travel — and thanks to the support of a caring and affluent family — she was free to devote her time and energy to her poetry. She hid from the world in order to write poetry that boldly confronted it."

In Newman’s book, the scholar uses Dickinson’s poetry to address the dominating questions of poet’s life, rather than the other way around. But still, the question remains: do readers’ fascination with Dickinson’s virginity distract from her poetry itself, and do we consider the erotic lives of male writers in the same way?

There’s a well-documented tradition of regarding the writing of women differently than the writing of men (male writers are hardly ever deemed “confessional”, female novelists are far more frequently suspected of writing “thinly veiled memoir” than their male peers, etc.). Dickinson is arguably no different — if she’s written vividly about sex, that means she must have been having some. (And if she’s having some, it must have been scandalous.) Never mind the fact that when the first writings about space travel and underwater odysseys were published — much of which was composed by men, and predates Dickinson’s poetry, sometimes by centuries — few questioned whether those writers had flown into space or walked on the bottom of the ocean.

But not all readers, nor fellow writers, consider Dickinson’s scandalized sex life an affront to the poet, or a way of detracting from the merits of her work. In a 2010 article, "A Bomb in Her Bosom: Emily Dickinson's Secret Life", published in The Guardian, Lyndall Gordon writes: “Stillness was not a retreat from life (as legend would have it) but her form of control. Far from the helplessness she played up at times, she was uncompromising…”

To explore this further, I reached out to fellow writer and reader Erin Bealmear, who recently adopted Emily Dickinson as her online dating persona, for the Electric Lit article "I Pretended to Be Emily Dickinson on an Online Dating Site." In the article (which may have a companion piece in the works — stay tuned!) Bealmear writes:

"Emily Dickinson has long been my go-to gal amongst my single lady heroes. She was a virgin, unmarried, and a recluse, but, man, was she talented. I began to wonder: How would Ms. Dickinson fare in the world of online dating? Would a lovelorn poet, obsessed with death and privacy, be able to woo a modern man?"

So, I asked Bealmear her thoughts: Do readers’ interest in Dickinson’s sex life (or lack thereof) detract from or enhance their interest in her writing? “Personally, I think her single status, her probable virginity, are appealing to women, particularly feminists, because it allows us to see her as an independent person, free from the chains of marriage and motherhood that bound most women at that time,” Bealmear says. “She wasn’t a typical nineteenth-century woman, and her single status, her virginity, are part of that. That said, I do think there is too much focus on her sex life, too much debate. Her accomplishments stand on their own. What she was doing or not doing in her bedroom shouldn't really matter.”

When given the choice, I’ll sooner take the feminist, self-determined Dickinson who chose her art over all else, over the timid recluse hiding romantic romps from her father and scribbling about them in her attic hideout later.

Perhaps it’s best to let Ms. Dickinson herself have the last word, with a poem that is often considered her poetic manifesto:

"Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth's superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —"