Books

True Crime Books Like 'Burned' Reveal The Flaws In The Criminal Justice System

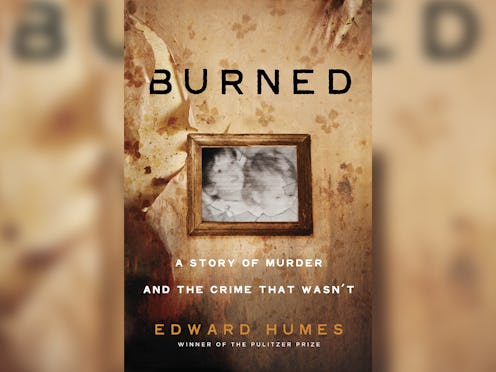

True crime has become a cornerstone of American culture. Viewers can't stop watching documentaries about serial killers, listeners can't get enough of podcasts about unsolved murders, and readers can't seem to scratch that true crime itch, no matter how many books about the topic come out every year. On the surface, this obsession with murder and mayhem can seem dark, disturbing, and maybe even a little distasteful. But underneath what appears to be not much more than a morbid form of entertainment is actually a very valuable teaching tool, one that continues to open up the public's eyes to the many flaws in our justice system. Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist Edward Humes's new book Burned — which explores the case of JoAnn Parks, a mother convicted of three counts of first-degree murder in the wake of a 1989 house fire — reveals how true crime can reveal the limits of forensic science, the biases at the heart of our legal systems, and the cultural myths that continue to stand in the way of real justice in the United States.

Just after midnight on April 9, 1989, JoAnn Parks appeared on her neighbors' doorstep in Southern California crying for help. Across the street, her own home was engulfed in flames. Trapped inside were her three small children. Despite efforts from neighbors, police, and firefighters to save them, both of Parks' daughters and her four-year-old son died. It was a tragedy that shook the community and changed the Parks family forever, but not just because of the loss of their children — because, two and a half years after the fire, JoAnn Paks would be charged, tried, and found guilty of intentionally setting her house on fire and murdering her own kids.

In 1993, the state of California found Parks guilty of three counts of first-degree murder and sentenced her to life in prison without the possibility of parole. During the trial, investigators testified that the fire was started intentionally by a human and not, as they originally thought in the days immediately following the incident, on accident by an electrical source. They also presented evidence that showed Parks' son was trapped in the closet by a hamper.

At the heart of the case against Parks is what Humes calls "fire mythology," a set of ideas about fires — what causes them, how they burn, and how they spread — that have been accepted as fact for decades without every being scientifically proven. As Humes explains, "Distinguishing accidental fires from intentional blazes remains one of the toughest challenges of forensic investigation, as arson is the one criminal act that consumes rather than creates vital trace evidence."

A year and a half after the tragedy at the Parks' apartment, a former police forensics expert John Lentini authored a report based on the devastating 1991 Oakland firestorm that made clear "Indicators of arson that had been passed on across generations of fire investigators, and that had been used to send people to prison for decades, were wrong. The same supposedly suspicious indicators occurred in accidental fires, too." And yet, fire mythology persists and even played a key role in sending Parks to prison for life.

Perhaps even more nefarious than the fire myth was the mother narrative the prosecution deployed during Parks's trial. Our country has a strict set of cultural norms that set good parents apart from bad ones, and according to the prosecution, Parks was a card carrying member of the latter group. One prosecutor even named her "one of the most evil defendants in Los Angeles history," but why? Not because she was a murder, but because she was, by their account, a bad mother.

"The prosecutor had spent considerable effort portraying her as a poor parent, heartless, selfish, untruthful, and, most of all, unmotherly," writes Humes. "A big part of the government's case boiled down to a claim that Parks hadn't 'acted right' during the fire and in its aftermath — as if there is any correct response to fire, trauma, deaths and loss. The allegations varied: She wasn't emotional enough. Or her emotions were an act. She didn't try very hard to turn back into the house and allowed herself to be restrained too easily."

According to Humes and legal experts, this kind of attack is "uniquely deployed against women in criminal trials" and often transforms fact-based cases into something that depends on "innuendo and personal smear tactics." It is also just one of a seemingly never-ending list of biases everyone from investigators and prosecutors to judges and juries to the media and the masses buy into over and over again. According to Burned, it was this subjectivity, bias, and the perceived value of acceptable narratives over complex facts — things that plague the entire justice system — that doomed Parks from the start.

Readers of Burned, be warned: it will be frustrating to learn about Parks' case — to see so clearly how flimsy and inaccurate the forensics evidence is, to read how biased just about every branch of the justice system is in not just this case but so many others — and to learn the woman still sits behind bars as of this writing. Raquel Cohen of the California Innocence Project, whose tireless work provided Humes with ample research material for this book, has taken up her case and continues to fight for Parks' freedom.

At the end of Burned, readers will walk away with clearer picture of the flaws of the American criminal justice system, and a glimmer of hope from the people working every day to fix it.