Books

Why This Author Believes Her Memoir About Sexual Abuse & Mental Illness Is A "Conjuring"

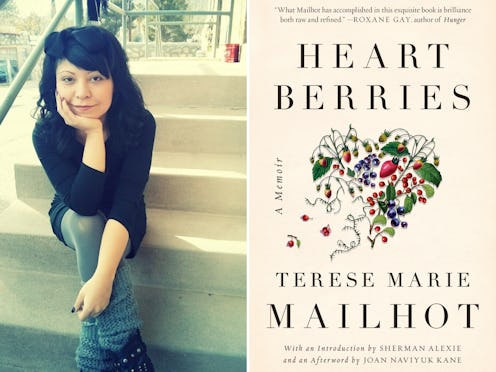

It took Terese Marie Mailhot four years to finish writing a single line about her father’s death. That line — "My father died at the Thunderbird Hotel on Flood Hope Road..." — can be found in her debut memoir, Heart Berries, published by Counterpoint Press. Written in the tradition of authors like Mary Karr and Jeannette Walls, Heart Berries is a poetic, coming-of-age memoir told through essays that explore everything from motherhood and daughterhood, to love and loss, to family and identity, to the intersections of art and mental illness, and more. Above all, perhaps, it is a story about women telling stories — the power of women speaking (or writing) hard truths about their lives.

Readers meet Mailhot in the wake of her hospitalization — after growing up in a family rife with dysfunction, grappling with an alcoholic father who molested her — she’s facing a dual diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder and bipolar II disorder. While hospitalized, Mailhot is allowed a notebook; and it is here that she begins to explore art and illness, what power writing one’s way out of trauma can have.

“I wanted to be at the apex of my story,” Mailhot tells Bustle. “For a long time, it felt as though things were happening to me. I felt as though I had no agency.” Despite Mailhot’s description of her experiences, she writers her narrator — herself — as the central actor in the memoir, rather than one who is being acted upon. Despite the predominant themes in Heart Berries: abuse, mental illness, destructive relationships — readers will have no doubt that Mailhot is a woman in charge of her own story. And it’s a story she, as evidenced on the page, isn’t afraid of.

Heart Berries: A Memoir by Terese Marie Mailhot, $15, Amazon

In one of Mailhot’s essays, "Indian Condition," she writes: "…I can name my pain so well that people are afraid of the consequences and power." It’s a theme that resonates with our current moment: from the #MeToo movement to Times Up, women are naming their pain (and subsequent power) in ways like never before.

"I wanted to be at the apex of my story,” Mailhot tells Bustle. “For a long time, it felt as though things were happening to me..."

“Naming it sometimes takes a lifetime,” says Mailhot. “I started [the essay] "Indian Sick" believing the problem was men, and then I realized it was something much larger. Naming the issue I had with being loved helped me understand where that really came from. Naming my issues with [my partner in the memoir] Casey helped me see that my real issue was I simply never told him I am scared he’ll leave me — I’m scared he doesn’t love me. I’m scared of abandonment, and saying I had abandonment issues felt like such a cliché, but it satisfied me.”

"Naming the issue I had with being loved helped me understand where that really came from."

Transforming that pain into art, however, can be a different story, as Mailhot explains. “Turning those revelations into art was a whole other thing,” she says. “I did it, though — and that helped me realize my power, beyond the pain. Being able to illustrate those experiences for readers was a triumph, because it took everything to resist all the urges I have as a human being to present myself as good, or healed, or undamaged. I had to work against myself to make the memoir, and I ended up more empowered than I ever thought I could be.”

It's worth nothing that Mailhot is wary of the word “resilience.” In the introduction to Heart Berries, fellow author Sherman Alexie writes about her resistance to the term. Later, in the essay "Indian Sick," Mailhot writes: "I believe we carry pain until we can reconcile with it through ceremony." I ask her about this.

“Resilience is one’s ability to endure and recover, and I don’t place much value on the word resilience. So many people did not survive, and they’re no less extraordinary. Ceremony is my mother holding up her hands in gratitude at my woman’s ceremony. It’s her hands in the air — telling our ancestors to witness me. It’s the healing that comes without much effort, but some practice — it feels immediate and confounds me.”

"I had to work against myself to make the memoir, and I ended up more empowered than I ever thought I could be.”

I wonder whether or not Heart Berries is a kind of ceremony to Mailhot’s experience, then. “I think Heart Berries is a conjuring,” she says. “It’s some type of incantation, where my mother becomes a god and the men who hurt me fall away. I laid it down and now the pain is lessened. Now my life has begun in a major way, somehow. It’s healing, and, while it took so long to hone, and craft, and speak — it felt powerful the whole time. I still receive a lot of power when I read the passages about my mother.”

Mailhot's mother and grandmother, and their own respective pain, feature prominently in Heart Berries, which has been described as a memorial to her mother — a social worker and activist herself. "My mother couldn’t really talk about what happened to her," Mailhot says. "It came out when she was angry. My grandmother could only combat what they did with grace and charity. I feel like these women gave me the dynamism I carry. And I carry them with me — my triumph is theirs, really."

“I think Heart Berries is a conjuring,” she says. “It’s some type of incantation, where my mother becomes a god and the men who hurt me fall away."

Heart Berries speaks not only to the pain and power of womanhood, but the unique experience of voicing one’s pain as a woman of color. Mailhot, who grew up on the Seabird Island Indian Reservation in the Pacific Northwest, writes not only as a woman, but as a woman of Native heritage as well.

“People are scared when Indian women name our culprits. People are so scared they have threatened to take jobs from women I love, because those women spoke up," she says. "People are hiding in the dark and we’re here just basking in the truth — and it’s frightening, but our fear is pure. It’s remarkable how we push ourselves through fear, and their shame is probably so heavy. People are scared to reconcile with the light — they’re scared to face what they’ve done to us. They’re so scared they’re sick — you can see it in their faces.”

In Heart Berries, Mailhot cites a creative writing professor who requested the class “not to write about abortions or car wrecks.” I ask her if “don’t write about this…” is perhaps just one more way to censor and silence women — and whether readers (and for example, critics of the #MeToo movement, and others) are actually finding these stories repetitive and stale, or whether they’re simply afraid of them?

“It’s weird. They either find these stories stale, or they’re so scared they can’t just say: ‘I’m scared of this content and it will hurt me to read it.’ Or, they could say, ‘I won’t be able to grapple with these experiences, or look at your work as art, because it’s too personal,’” Mailhot, now an instructor herself, says. “It’s nonfiction, buddy. What are we doing if we’re not interrogating the self, even when we write about something unrelated? It’s all deeply personal, even when it’s coming from someone who assumes they’re removed from the subject. It’s weird, because many students are eager to talk about their lives. They want to talk about the car wreck, or the abortion, or the sexual violence they experienced. We should be helping them speak their stories. We shouldn’t be trying to steer them towards anything else, even if we believe they could benefit from writing outside of what they know. I don’t believe it’s our job as instructors to tell them what should inspire them — it’s our job to give them the tools to outdo themselves — to help them communicate something.”

Heart Berries: A Memoir by Terese Marie Mailhot, $15, Amazon