News

Senate Rule 19 Has A Violent History Among Dems

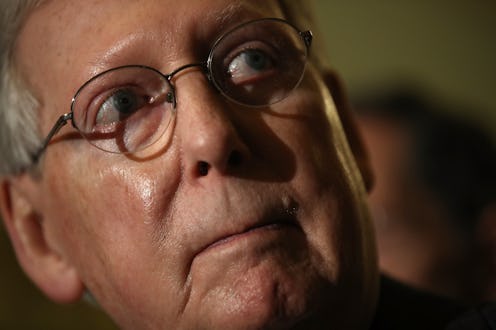

If you're a Democrat or a progressive, there's a great chance you've heard what just happened. In the midst of the ongoing Senate debate over President Trump's nominee for attorney general, Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions, Majority Leader Mitch McConnell invoked an arcane rule. The invocation of Senate Rule XIX stopped Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren from reading a 1986 letter by Coretta Scott King opposing Session's bid for a federal judgeship. Which raises the question: Why was Senate Rule XIX created, and what purpose does it serve?

It's actually a rather dark and peculiar story, as many have pointed out. The rule dates back to when a physical fight broke out between a pair of senators back in 1902, both of them hailing from the Palmetto State. Benjamin Tillman was South Carolina's senior senator, while John McLaurin was the junior senator; both of them were Democrats.

It's important to remember, the early 1900s were still a time in which the Democratic Party was strong throughout the American south, in no small part thanks to its indulgence of racist and white supremacist politics. It would take decades for the roles of the two major parties to flip, with the Democrats becoming a more northern, coastal-oriented party that favored civil rights, and the Republicans becoming the party far more in touch with, and catering to, white racism and animus.

As Derek Hawkins of The Washington Post detailed, Tillman and McLaurin came to blows. Tillman had excoriated the absent McLaurin until he arrived on the Senate floor, and angrily accused Tillman of spreading a "malicious" lie against him. That led Tillman to attack McLaurin, setting off a melee that also embroiled other members of the Senate, and which ultimately spurred the passage of Rule XIX. In other words, the whole idea was to prevent violent physical conflict by imposing a minimum standard of decorum.

It's worth noting that there are some strange and unsettling historical echoes at work here, too. After the rule was invoked against Warren ― for reading aloud concerns about Sessions' attitudes toward civil rights and black people from the widow of Dr. Martin Luther King, no less ― Ben Mathis-Lilley noted for Slate that Tillman, the man whose violent outburst necessitated the rule, was a monstrous racist of the highest order, and an open supporter of lynching.

As a blunt example, when President Theodore Roosevelt welcomed Booker T. Washington to the White House for dinner in 1901, Tillman's response was about as disgusting an expression of violent white supremacy as it gets. As quoted in Born to Rebel, the autobiography of civil rights leader and minister Benjamin Mays, Tillman called for a thousand lynchings across the south to teach black people their place.

The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that n***** will necessitate our killing a thousand n*****s in the South before they learn their place again.

In other words, Rule XIX was created in direct response to a violent outburst by a genocidal white supremacist. And on Tuesday night, it was used to effectively silence the posthumous concerns of Mrs. King, the wife of the most famous civil rights icon in American history, about Sessions' views on race, civil rights, and voting rights. You really couldn't dream up a more unsettling arc of history for a Senate rule than that.

The origin of the rule also highlights the absurdity of invoking it against Warren in the manner in which McConnell did, unless he somehow knew Sessions was about to burst through the wall and put her in a suplex. While the desire for comity and restraint between senators makes sense, there was no hint of physical antagonism or threat to Warren's remarks, and they were delivered in the context of a cabinet confirmation debate. The fact that Warren was flagged for speaking ill of a colleague who's vying to leave the senate, amid a debate about that colleague's fitness to be attorney general, is more than a little absurd, and plainly not the rule's intent.

As these things often go, however, McConnell's heavy-handed approach has surely sparked more attention and awareness than there would otherwise be, both on Warren's opposition to Sessions and on King's letter denouncing him back in 1986. In other words, a supreme backfire that never should've happened, but one that the Democrats are entirely pleased about.