How I Learned Gender

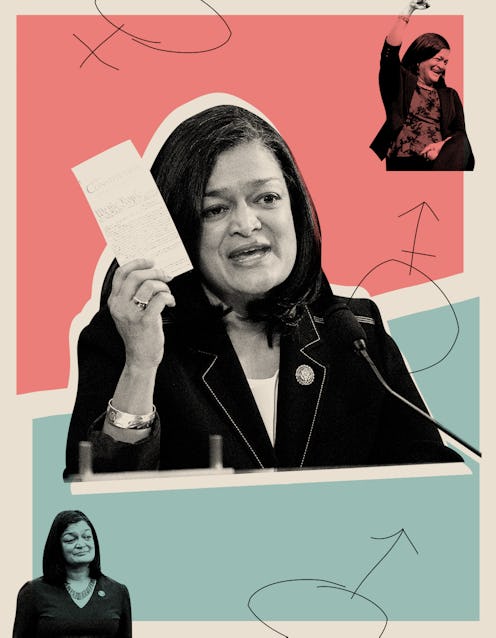

“They’ve Shifted Everything”: Pramila Jayapal On Raising A Nonbinary Child

The Democratic congresswoman unpacks her understanding of gender.

In “How I Learned Gender,” Bustle talks to cultural hotshots about their journeys with gender identity, expectations, fluidity, and the ways that pink and blue blankets inevitably shape our lives. First up is Washington Rep. Pramila Jayapal, a stalwart progressive who's serving her second term in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Eight months into Pramila Jayapal's first term in the U.S. House of Representatives, she was referred to as a "young lady" on the House floor. The offender was 84-year-old Republican Rep. Don Young from Alaska, who then told the Seattle congresswoman, his peer, that she didn't "know a d*mn thing." She was 51 years old, with a 22-year-old child, in 2017. Jayapal responded in stride, invoking a House procedural policy, and asked Speaker Nancy Pelosi for Young's words be "taken down."

"People underestimate me because I’m brown, and I’m a woman, and I’m an immigrant," she tells Bustle — and at their own peril, honestly. Since entering Congress, she's sparred with Amazon, mentored younger progressives like Reps. Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and has been anointed co-chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. In her new book, Use the Power You Have: A Brown Woman’s Guide to Politics and Political Change, the veteran activist writes about her childhood in India and Indonesia, moving stateside at 16, and raising a nonbinary child. She talks to Bustle about her ongoing journey with gender.

How were you initially taught gender?

It was unquestioned that I was a girl. I was in India [and] Indonesia, places where there was no fluid concept of gender. My mom and dad were happy to have girls. And while I knew that, my sister would say, “A little boy is coming!” when my mom was pregnant with me, because the cultural pressure was so strong.

And what about what’s expected of girls and boys? When did that crystallize?

At a very early age. It’s hard to be in India and not see that. My grandmother was beloved by me and her grandchildren, but we saw how my grandfather treated her. She was expected to be in the house, to make the meals. He would get angry with her when something was out of place on the table. My dad had similar tendencies with my mother.

Your book made me think about my own family. My grandparents were Holocaust survivors who wanted me to be a doctor or lawyer — but also said a woman couldn’t be president. They could hold both truths at once. You write about your family similarly.

It was less about gender and more about class. There was always this pride that I was going to work in investment banking, even though it wasn’t what I wanted to do. Doing nonprofit or social-justice work was seen as voluntary, and it was gendered. That was what housewives did with their free time, not what someone who’d crossed the ocean with their family’s remaining savings would do. Men worked in finance, men were successful, men were CEOs. If you wanted to be successful, you had to choose that path.

And obviously you didn’t. Did anything surprise you when you joined Congress, in terms of representation?

It just cemented how much work we have to do. I think I’m the only member out — if that’s the right word — about having a nonbinary child. I think there are other members who have nonbinary kids, but they’re not talking about it publicly.

How has having a nonbinary child, Janak, changed how you understand gender?

They’ve shifted everything. I was an early supporter of LGBTQ rights, but I didn’t understand gender fluidity. When they told me they were nonbinary, it [opened] a door into a new set of gender politics for me. My mother is a therapist, and she works with LGBTQ folks. Many therapists in India don’t. When Janak came out, she took a six-week course on trans and nonbinary people. She is really trying! It’s hard to find the right words when you’re 80 years old.

Did you ever question the gender binary before Janak?

Ursula Le Guin was a dear friend and writing mentor of mine. A lot of her books eschew any sense of traditional gender. When I was in my early 30s, I started to wonder, “Why do we have these genders anyway?” At that time I still understood it to be a binary, but Ursula’s writing made me question what was real, what was science, and what was possible.

Her work often leans on, and then plays with, gender stereotypes. In your book, you talk about needing to regulate your emotions because of how they'll be perceived. Can you explain that?

I think it’s tied to stereotypes, this idea of intellectual versus emotional. And it’s deep. If you display or express emotion, which is something women have been trained to do, you are not seen as smart or analytical.

That’s one thing I hear from women I mentor: “I’m tired of managing these things.” Being the first woman in any context is challenging — and this is also true when you’re the first nonbinary person, the first trans person, the first person of color. Because you’re operating in a world that’s not yours. You’re trying to change it as you come in the door.

Has holding multiple marginalized identities affected your work?

When I came to Congress, one of the senior staff said to me, “You work on so many issues and everything’s a priority for you. Most members have more success when they just pick one.” I remember looking at him and saying, “I just can’t.” I need to lead on as many of these things as I can handle. It’s like when I wrote the abortion op-ed, and in it wrote about “pregnant people” and not “women.” People were furious because they felt I was trying to strip away at a critical women’s issue. Other people wrote thanking me for understanding that this is an issue that doesn’t just impact women. That’s the tension.

And a final question: What’s the most critical thing Americans should focus on right now?

Right now, we’re being called to confront a quadruple pandemic: COVID-19, economic devastation, police brutality, and anti-Blackness — and Donald Trump, who is an egotistical, xenophobic, misogynistic, and corrupt president. It isn’t possible to focus on one thing. Those supremacies all encompass gender within them. That’s how we need to approach the world.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.