Rule Breakers

It's Thanksgiving. I Dare You To Start A Conversation About The Washington Football Team.

You might be surprised by what you don't know about the origins of its former name, the Redskins.

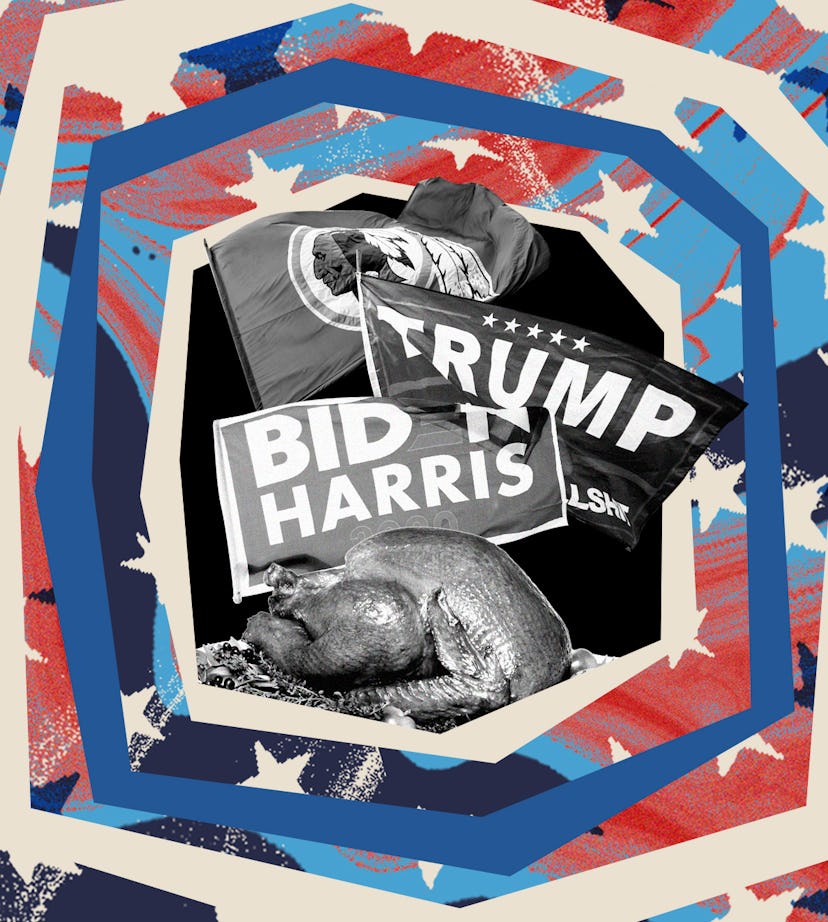

Hey ya’ll, it’s that time of year again. No, not the holiday. I’m talking about that brief post-election period when the liberal voters in blue dot cities gather together and talk about disowning their red-voting relatives. I understand the sentiment. Especially in a year in which we narrowly escaped Trump’s specifically racist and misogynist branding of the Republican Party. But as we bow our heads and give thanks for college educations, ethnically diverse friend groups, and news sources that aren’t Facebook feeds from fly-over states, I want you to remember one thing: people aren’t racist, misogynistic, queer- or xenophobic because they are unintelligent, backward, and cruel—whiteness is.

The distinction is important to make because the narrative that whiteness is the standard for what is good, wholesome, and protective of our nation is deeply ingrained in the United States history. When white voters on the left (and it is still majority white) become new champions in the fight against voters on the right (predominantly white, but not entirely), it is a continuation of the same old story, and not a progressive one. Progressing past the uglier parts of American history is not about disowning relatives you don’t agree with, but about recognizing how the same logic that makes them insufferable still lives in, and benefits, you. White supremacy thrives in America because white culture at-large rejects the parts of American history that make it look bad.

This is true for Republicans and Democrats, and a great example can be found in America’s favorite autumn pastime, football. This year, the Washington Redskins finally changed their name, which Indigenous nations have been protesting since the 1960s, to the Washington Football Team. Although liberals and conservatives might have had different reasons for looking the other way, it kind of all boiled down to their fandom being stronger than their allegiance to anything else. For decades, white culture wrote off changing the Washington team name as a gesture of political correctness, a position that — whether you were for it or against it — glossed over the term’s real historical role in the recruitment of average Americans to state-sanctioned genocide.

Progressing past the uglier parts of American history is not about disowning relatives you don’t agree with, but about recognizing how the same logic that makes them insufferable still lives in, and benefits, you.

As historian Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz, author of The Indigenous People’s History of the United States, described in a 2018 interview, the term “redskin” originated in the Massachusetts Bay Colony of the 1600s where officials first offered a bounty for collected Indian heads. “That’s what [the English] had done in the conquest of Ireland to terrify the people,” and those principles migrated to America by way of not only English and French settlers who warred with Indigenous people in skirmishes, but also merchants—like the Dutch East India Company—who wanted the land cleared of First Nations settlements without getting their hands dirty. Scalps became more popular to collect than heads because they were easier to carry and easy to trade as currency, which made scalping a booming business. “It’s very hard to tell with a scalp whether it’s a child, or an old person[, ...] so anyone can go and kill an Indian, scalp the person or cut their head off, and collect money for it,” she writes. Although some scholars have argued that “redskins” was a name “Indians” invented to differentiate themselves from white and Black people, or a reference to the red face paint certain tribes would wear during war, Dunbar-Ortiz puts it this way: Americans “called the bloody bodies that were left [behind from scalping], these corpses covered in blood because of that mutilation, ‘red-skins.’” Documentation of scalping bounties continued for 200 years—from the Phips Proclamation of 1755, all the way up through The Daily Republican newspaper of Winona, Minnesota in 1863, where an ad lists a price of $200 “for every red-skin sent to purgatory.”

Despite living on Indigenous land, people in the United States rarely give a second thought to the discrimination we still practice against them. The Senate, for example, has recognized the Iroquois Confederacy—the world’s oldest participatory democracy—as the model upon which the U.S. government was based since 1988 ... but I’ve never heard this mentioned in any bipartisan conversation about “our founding fathers” or American freedom. Aside from maybe a quick mention during this time of year, Americans are hush-emoji quiet about the “the Indian War”, the centuries of battles fought by white settlers against the 12,000 First Nation tribes that strengthened the U.S. military into a superpower. The coast-to-coast battles that whittled Indigenous people down from 60 million strong back in 1142, when “The Great League of Peace” was holding it down for democracy, to the current population of 2 million was a feat involving bioterrorism (the infamous small pox blankets), and government-incentivized murder.

In divisive times, there is power in relearning what we think we know about American culture. The past is a great reminder of how we ended up here in the present. No side is immune. We can’t speak up for justice while treating unfavorable aspects of American history and its people beneath us. We have to re-educate and redirect. But we can’t start with problematic family members, we have to start with us.