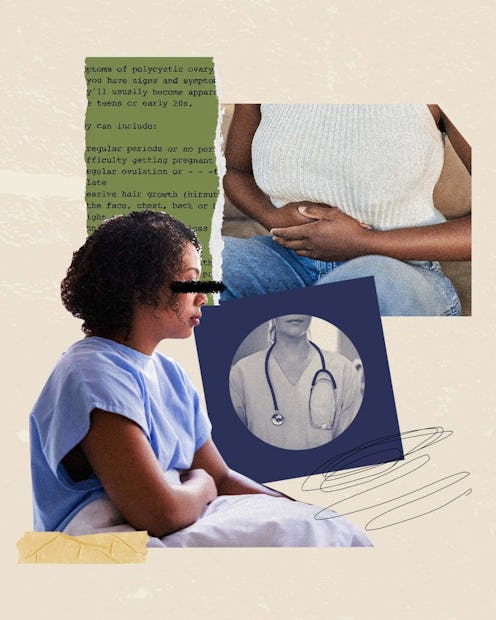

Health

The Lessons I Learnt Trying To Get My PCOS Diagnosis As A Black Woman

Navigating the UK healthcare system as a woman is hard. Navigating it as a Black woman is even harder.

The first lesson came very early on: don’t fall down a Google rabbit hole.

It’s late and, once again, I’m spending hours scrolling through countless, illegitimate medical websites, jumping to the worst possible conclusions. Months of confusion and pain have led me here. Pain that has made it hard to be anywhere but bed every time my period hits. Confusion about why, at 21, I am living with worse acne than I did as a teenager and why I need to shave my legs practically daily. I am desperate for answers and I can’t stop searching.

I am increasingly terrified reading about all of the things that could possibly be wrong with me, seeing words such as “diabetes” and “heart disease” flash up on the screen. But then something on the NHS website catches my eye: polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS.

“Polycystic ovaries contain a large number of harmless follicles that are up to 8mm (approximately 0.3in) in size,” the site reads. “The follicles are underdeveloped sacs in which eggs develop. In PCOS, these sacs are often unable to release an egg, which means ovulation does not take place.”

Back then, these were simply words on a page – they held no meaning for me – and yet they still had the ability to send me into a state of panic. I continued reading and my anxiety skyrocketed as I learnt that one in ten women have PCOS and, according to the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Black women are affected more severely than others.

Maybe that’s where I should have stopped scrolling, gone to bed, and called my doctor the next day. But I didn’t. I scrolled deeper, learning that PCOS is one of the leading causes of infertility and can increase the risk of endometrial cancer. I couldn’t sleep at all after reading that.

A few weeks passed and I was entirely too petrified by my internet discoveries to even think about acting on them. I suppressed the thoughts and carried on with my life until my period came again and the worry caught up with me.

The next lesson was a nice one. I decided to speak to my friends about my concerns and learnt that the old saying is true: a worry shared really is a worry halved.

After sending a message in the group chat, my girls met my concerns with a perfect combination of comfort and rationality. They have somehow mastered the art of making stern advice feel like a warm hug. They let me know how sorry they were about what I was experiencing while also talking me down from my anxious state and advising me to reach out for help.

I listened to their advice, which led me to another nice lesson: a positive and proactive GP really does make all the difference. I called my doctor the next day to discuss my symptoms and she was everything I could hope for – a woman who didn’t make me feel as though I was being dramatic, listened to my concerns and calmed my worries. She suggested that I book a blood test as soon as possible.

I saw a nurse who took my blood and let me know I’d have some results by the next week. They were testing for hormonal imbalance, which would be one of the first indicators of PCOS. The results didn’t take long to come and I eventually learnt that my LH hormone levels were higher than my FSH hormone levels, an imbalance that often interferes with ovulation. From there, my GP put a request in for me to have an ultrasound of my ovaries, uterus, and bladder, which would confirm our concerns and, ultimately, lead to a diagnosis.

The next few months taught me another valuable lesson: the waiting is the worst part. While my GP was attentive as can be, the system she worked within wasn’t. Months went by and I didn’t hear a thing about my scan. With every day that passed, my concern grew. But all I could do was wait.

In the end, it took about three months to receive the call. This is where I learnt one of the hardest lessons of all: the medical system can reject you. It can literally reject you. The doctor on the other end of the line told me that my request for a scan had been denied. I didn’t even know that was a possibility. I was lucky enough to have little experience navigating the healthcare system but I didn’t expect to simply be told “no, we won’t help you.”

This hurt. All of a sudden, my anxieties about not being believed rushed to the surface. The doctor told me that they didn’t believe I have PCOS as, despite everything, my period still came monthly. But I knew from my research that bleeding doesn’t equate to ovulation. Instead, it can be “anovulation”.

Luckily, my GP wasn’t shaken. She calmly let me know she was going to make an appeal and, as a result of her perseverance, I was finally booked in for a scan.

The scan was two weeks later and, for those fourteen days I slipped back into my old Googling habits in an attempt to prepare myself for this invasive procedure. I was pretty petrified and the cartoon diagrams online did very little to assuage my fears.

On my arrival, I was checked in and shortly shown into a small room with two middle-aged white women. I expected a warm welcome, with two mum-like figures who would calm my nerves – but I couldn’t have been more wrong. The room felt cold and not due to the temperature. They gave me basic instructions on what I needed to do with no attempt to ease my nerves or to engage in small talk to lessen the too-close-for-comfort awkwardness of the procedure.

To my surprise, the scan itself didn’t make me uncomfortable, but the interaction with the nurses did. And so, I learnt another lesson: medical professionals aren’t always that professional. Or kind. Or helpful. Despite the relief that the scan itself only brought me only mild discomfort, I couldn’t shake the nurses’ treatment, which was even more hurtful when I heard them burst into bright conversation with one another after I left the room.

I immediately took to the group chat to share my experience. Once again, my friends were comforting but honest, attributing what happened to my Black skin. I knew about racism, I knew about medical racism, and yet I was horrified to think that this could have happened to me. I was aware of the reasons why Black women are so often disregarded by healthcare professionals and why they often suffered poorer outcomes than their white counterparts. It’s because we’re not perceived as fragile or vulnerable. Our fears and our pain is often undermined. We are simply “strong Black women” and so there is never much attempt to treat us with softness. However, knowing all that still didn’t prepare me for experiencing it first hand.

I suppose the final lesson was the biggest of them all, although it didn’t feel like it at the time. It came after the phone call that finally confirmed I had PCOS. “Yeah, I thought so” were the exact words I uttered when the doctor told me and, honestly, the main emotion I felt was relief. I was relieved to have an explanation for the horrible symptoms and some sort of conclusion after months of unanswered questions.

The lesson was to always trust myself. I was consoled by the fact I had been persistent enough to fight for a diagnosis despite the constant knock-backs that almost convinced me to stay silent. While the journey to my diagnosis – the waiting, the rejections, the gaslighting, the mistreatment – hurt more than it healed, finally I had an answer. I was proud of the fact that I hadn’t given up and had demanded the best for my body.