Health

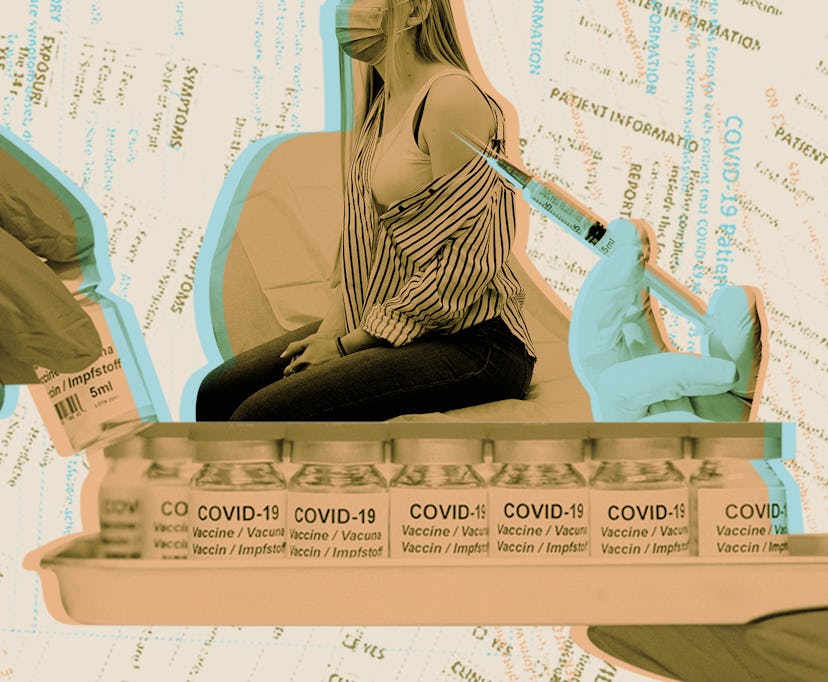

What It’s Like To Be In A COVID-19 Vaccine Trial

Two injections, some side effects, and major peace of mind.

Amanda has never tested positive for COVID-19, but she’s had symptoms two separate times since the coronavirus pandemic first hit the United States this spring. Both times, in April and June, she had incredible chest pains, fatigue, night sweats, and diarrhea — all known COVID symptoms. Both times, she lost her sense of taste and smell, and got pinkeye. She even had two brain strokes, a possible complication of COVID reported by up to 6% of patients.

But even at her sickest, the south Florida resident felt it didn’t compare to the severe cases of COVID she’d read about, especially fatal ones. “I just felt so guilty,” Amanda tells Bustle. “I felt like I was given another chance at life and had to do something to acknowledge that it was a miracle to still be here today.”

That’s why the 28-year-old law student decided to become one of the 44,000 participants volunteering to stop the pandemic as we know it by taking part in Pfizer’s Phase 3 clinical trial for their COVID-19 vaccine. Since she tested negative each time she got sick, and has tested negative for antibodies, she was able to participate. The pharmaceutical company is one of many racing to get the first FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccine to market. Like its closest competitors Moderna and AstraZeneca, Pfizer has promised not to submit the vaccine for review until its safety and efficacy have been proven in a clinical trial. Already, AstraZeneca's and Johnson & Johnson's trials had to restart after participants got sick — a sign that safety concerns are of the utmost importance through this process.

If Pfizer's vaccine is safe and prevents or reduces the severity of COVID infections in at least half of participants — a process that involves comparing cases of COVID among the people who received the vaccine and those who got the placebo — it could request emergency FDA approval. Already, the company is manufacturing the vaccine to have 100 million doses ready by the end of 2020, in case it works.

What The COVID Vaccine Trial Is Like

Having spent a few years pursuing pharmacy school before shifting towards law, Amanda still thinks of herself as a “scientist,” and felt excited to be part of a significant public health effort. Still, she says she wouldn’t have felt comfortable participating until Phase 3, citing fears that the government has pressured companies to fast-track vaccine development. The way Pfizer’s CEO has publicly pushed back against politicizing the vaccine race set her at ease.

Phase 3 clinical trials are double-blind, so Amanda doesn’t know if the two shots she’s received were vaccine or placebo. Before receiving each of her injections, she had to take a COVID test and a pregnancy test, and she’s supposed to stay on birth control through the duration of the trial. Volunteers need to be 12 or older, not pregnant, "in good general health," and not previously diagnosed with COVID in order to qualify. On top of seven in-person check-ups, she completes a monthly survey about her general health through an app, and will do so for 14 months after her appointments end. She was instructed to proceed with her life as she had before the clinical trial — to continue to take “every precaution” against getting the virus, since she wouldn’t know if she’d gotten the vaccine or not.

Of getting the shots themselves, Amanda says the process is intense. “You’re not allowed to look at it,” she says. “You can’t see the color. You can’t see how much is in it. You can’t see the size of the needle. You can’t see anything.” Once the injections were administered, the team sat with Amanda for two minutes to observe any reactions, and then were replaced by a separate team, who waited with her for another 30 minutes.

One Vaccine Trial Volunteer's Side Effects

So far, Amanda would describe her participation as a minor inconvenience, though she’s dealt with some side effects. After her first injection, on Sept. 11, she says her eyes went bloodshot within minutes of receiving it. Then, she felt like she tasted and smelled cardboard. While Amanda was in her car, preparing to make the 45-minute drive back home, her chest broke out in a blotchy, warm rash, the left side of her throat swelled, and her ears turned red and hot. Ten minutes later, she says,“it all went away like it never even happened.” That night, she got hit with a wave of chills and exhaustion, then was fine the next morning. Four days later, she woke up in the middle of the night with “the worst explosive diarrhea” she’s ever had.

In the two weeks between the first and second injection, she says she didn’t have any other symptoms. The second time around, she said she felt exhausted the day of the shot, but that was about it. A few days later, she got another wave of diarrhea that resolved the next morning. She says she contacted Pfizer through the symptom-tracker app about her intense diarrhea, and was told to rest, but to notify them if things worsened or if she also developed a fever. By the next day, her diarrhea was done, and a fever never came. Pfizer’s preliminary reported side effects are fever, chills, headaches, and joint pain, which are already commonly associated with vaccination.

Her compensation for going through all this? If it turns out she actually got the placebo, she’ll get the vaccine for free once it’s deemed safe. She also gets paid $120 for each of the in-person appointments she has to attend, and an additional $5 a month for completing Pfizer’s symptom survey online.

But the financial benefits matter less to Amanda than the peace of mind she now feels. Though Amanda won’t know for sure whether she got the vaccine or the placebo until the final product is out, she thinks that already, she’s been protected from contracting COVID for what she believes would be a third time. She learned she had been exposed to COVID again after going to her apartment complex's pool with a number of people who had active COVID cases, but then tested negative once again.

“I was perfectly fine,” Amanda says. She felt so emboldened, she says, that a few weekends later, she went to the beach and out to bars with friends. “I think it actually works.”

This article was originally published on