Entertainment

Unwrapping 'Masters of Sex' With Its Creator

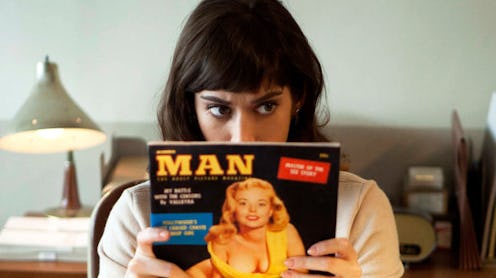

The presentation of women on television has a longstanding history of one dimensionality. Though, thankfully — albeit slowly — that tide is beginning to turn. Women on television have become just as varied, alluring, confusing, loved, hated, complex, and fully realized as the men. And nowhere is that more evident than in Masters of Sex , the Showtime series (and book by Thomas Maier) recently nominated for a Golden Globe and heading into its season finale on Sunday. The drama is often heralded as a Mad Men for the sexy science set, but its biggest draw is in its star, Virginia Johnson (played expertly by Lizzy Caplan). She's the most complicated woman on TV, and bringing her to life is no small feat.

Perhaps it's because in many ways, Virginia Johnson is not like most women we see on television. Which is fairly easy to say about, well, most women but hers is a special sort of unique. Johnson was no open book, despite misconceptions from undiscerning and/or misogynist eyes out there, given her fluid and carefree attitude about sex. She was ambitious, determined, and cavalier about her lovelife. She wanted more than anything to be in command of her own ship, metaphorically speaking. This drive pushed her into a series of jobs and unfinished college programs — from an insurance agency, to band singer, to business writer — before landing her on the secretarial desk of Dr. William Masters. She's a character you have to really think about, making for many a conversation between the show's creator Michelle Ashford and her writers' room.

"People have spent a lot of time thinking about her," explained Ashford in a phone interview with Bustle. Writers "are required to sit down and really deeply think about her and what was really going on with her for a very long time."

Johnson was, in many ways, a product of her own circumstances and environment. At the time of her interviews with Maier, Johnson was well past 70 and looking to make sense of her own life trajectory — from Masters to her children and even the man she lost her virginity to, Gordon Garrett — and through this, many discrepancies and disjointed intentions arose. From whether or not she loved Bill to how she could separate sex and love, she ebbed and flowed along the path of uncertainty, unable to fully understand her own machinations in life and love.

"This is what I mean about her," explained Ashford. "We have the greatest affection and fondness for her but we do have the sense that there was a curious sort of agenda, whether intentional or not, about giving an interview with Thomas Maier at that point in her life."

And that's where the show brilliantly fills in the blanks, bringing a conflicted, incomplete, constantly-evolving, and fully-realized woman to life. Virginia Johnson is far from perfect, but she's required viewing for anyone interested in seeing how far we've come in defining women's roles on television.

Now might be a good time to note that there will be some moderately sized plot spoilers ahead for those unfamiliar with the life and times of Masters and Johnson outside of the series. Turn away now if you prefer to be blissfully unaware.

JOHNSON AND SEX

Though the two began as colleagues, they quickly entrenched themselves in the study — evolving into sexual partners in the name of science — and much later, husband and wife. Though she was friendly with Masters' wife the whole time, Johnson, at least outwardly, showed few outward signs of remorse regarding the duo's arrangement pre- and post- the Masters' divorce. "I knew her well and we liked one another in a way," Johnson explained to Maier. "I think we would have been pleased to conspire against him, but she didn't quite have the sophistication to do that."

When speaking with Ashford about the same quote, the frustratingly human aspects of Johnson's behavior become clear.

"One of the things I struggle with most, considering she was very friendly with Libby, is what was she saying to herself about what she was doing? ... There’s lots to be discovered about what Virginia Johnson was telling herself about her physical relationship with Masters while she was friends with Masters’ wife. That’s one of the most complicated trials, ever. What is really fun is looking at that quote and going 'Hmm…what was really going on in her head when she said something like that?' and 'What is she trying to cover up in an era she felt sort of vulnerable in?' and 'what of this is revisionist history here?'"

Their unconventional relationship cannot be stressed enough: these were two people with very high opinions of themselves, who refused to be easily defined by broad-stated declaratives, or the methodology behind their own thoughts and actions. While writing his 2009 book on which the series is based, author Thomas Maier got to see a side of Johnson that contained equal parts fan dance and reflective thoughtfulness about her life. Johnson was keenly aware of not only her own duality, but its inherent presence in others (whether they accepted it or not).

"She understood people as a mess of varying emotions and contradictions, and Bill Masters was the science; he was the other side of the coin," explained Maier.

But Johnson's own farm-raised upbringing lent to her straightforward views on sexual relations, perhaps being more in tune with the animalistic nature of it than most. "She said, 'I grew up on a farm, I know all the aspects of animal husbandry,'" explained Maier.

At the same time, Johnson was the one to convince people to take their clothes off, to hop on the table, to strap on the camera/dildo Ulysses, or take part in a couples-based sexual encounter. She was charismatic and intuitive, and drove the entire ship given that she was able to coalesce people in a way that Masters' scientific breeding made impossible.

JOHNSON AND LOVE

And even though she made astute observations on the mental and emotional states of those around her, her own understanding of love was still a mystery, even years later. Following the release of Masters of Sex in 2009, Maier once again found himself entrenched in Johnson's seemingly never-ending dissection of her feelings towards Bill, who divorced Johnson in 1992 in order to marry the "love of his life," a childhood sweetheart named Dody. She was 67-years-old and had dedicated her entire life to this man.

But she was adamant throughout most of the interviews that preceded the book that she never really loved Masters. "I think it was a marriage of business," explained Torrey Foster, the Masters and Johnson clinic's first attorney — and a sharp critic of Johnson's from the get-go. "I don't think they really had a close, intimate husband-wife relationship. It was more contractual."

They were only married, after all, as a way for Masters to ensure their partnership continued after Johnson was tempted away by a Philadelphia-based suitor. But still, after looking back on things, Johnson changed her tune. "I talked to Virginia about [the book] and she said, ‘You know, I guess I did love him.’" But Maier wasn't wholly convinced she accepted the thought herself. "It wasn’t particularly convincing, the way she said it, but to this day we’re still scratching our heads."

But theirs may not have been a love in the traditional sense. "Of course they loved each other, on some level — they were fascinated by each other."

Here is a woman who would not allow society to define her but in doing so, made herself a target of a lot of criticism (sometimes rightly so); her relationship with Bill Masters being the biggest example of this. Friends with Masters' wife throughout the whole of her scientifically excused affair, many were quick to dismiss Johnson as a nothing more than a determined mistress. "There’s a whole camp of people who were essentially Libby’s friends and family who felt that Virginia, from day one, wanted to break up Bill’s marriage and she wanted Bill for herself. [Virginia] certainly denied that," explained Maier.

"But even people like Bill’s friend Dr. Kolodny, who often butted heads with Virginia on a lot of matters), said 'Oh no, she wasn’t plotting to break up his marriage, it was a lot more complicated than that,'" according to Maier.

JOHNSON AND TV

So how do you bring that character onto the small screen, when it presses so hard against the tropes and easily digestible stereotypes people prefer their on-screen women to embody? When the only definitive work on her life is a jumble of unconventional relationship structures and the subject's own what-may-have-been, what-could-have-been, and what-I-wish-had-been? Coupled, no less, with the decidedly unkind attitude society had towards all women during the 40s and 50s?

You get someone like Michelle Ashford, keenly aware of the limitations and opportunities presented in portraying this woman on-screen. In her own right, Ashford is as wary to accept her work as a groundbreaking effort as Johnson was to be considered a feminist. Both women simply see and do, well, themselves. They do not want labels, nor lofty ambitious pressures shoved upon their helms — so much can change or become distorted when such ideals are imposed on anyone. At any point, if anything they do contradicts these so-called ideals that they didn't ask for, it's rallied against with a high-octane fervor. Which is where the dimensionality comes in.

And, as Caplan put it in a recent interview, "everything [Johnson] does is a series of contradictions." And indeed she was. Johnson's was a life of dual existence: she was sexually liberated, twice-divorced, a single mother, and emotionally short-sighted in her own romantic endeavors throughout the lot of it. For her, the line between head and heart was one that should be thoughtfully measured, and kept separate at all costs. With such a pragmatic attitude it's no wonder she quickly became Masters' most invaluable asset.

But if you're expecting Ashford to answer those questions Johnson could not, you're just as mistaken as those that feel she can be pegged.

"We’re not going to have her life end where she’s resolved and happy and content and sure of her place in the universe and it all works out and is great for her," explained Ashford. "And I think when you read that book it shows you that you have to be faithful to at least some kind of second-thinking, regret — anything along those lines in terms of how this played out and her choices in her life."

Perhaps that's because Johnson, more than anything, was a bit of a trigger. To herself and the world around her. She was outspoken and progressive; she was determined and unconventional, and she was highly, highly ambitious — all things that were considered garish and unwelcome to the modern '50s woman's arsenal.

And while it may make for a less-than-shiny picture of a very important woman, it's a more complex and interesting picture of working-through-it femininity than we've really ever seen on television. And a necessary one to boot.

Image: Showtime [3]; George Tames/New York Times [1]