News

The Democratic Debate Touched On Race

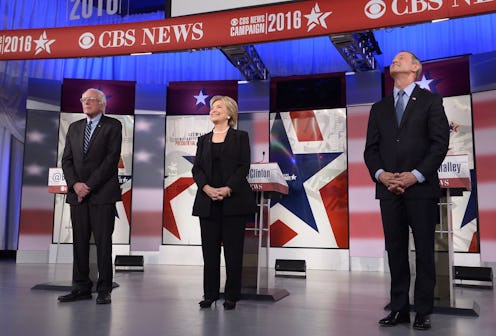

Well, the big night is all over and done with — the second Democratic presidential debate is now in the books, and it was a serious, policy-driven, and somewhat contentious affair. We finally got to see the candidates get a little more aggressive with another another, a sure sign that the primary season will soon be upon us, and they touched on an array of different issues, from terrorism, to economics, to the minimum wage, and yes, to the state of race and policing in America. Here's how the Democratic candidates answered on race, because racial justice is as vital and urgent an issue as any in the progressive movement.

The question was put to the trio by CBS' lead moderator John Dickerson, and it was the only time that race came up in the debate — it was also raised during the first Democratic debate on CNN, but it hasn't played as central a role so far as it could have.

After tackling health care policy, ISIS and terrorism, and Wall Street reform, Dickerson got the candidates on-the-record on racial justice. Here's what Dickerson asked each candidate, followed by how each of them replied — all credit to the Washington Post's transcript of the debate.

Martin O'Malley

Dickerson's first question was posed to O'Malley, referencing the so-called "Ferguson effect" invoked recently by FBI director James Comey.

Governor O'Malley, let me ask you a question. The head of the FBI recently said it might be possible that some police forces are not enforcing the law, because they're worried about being caught on camera. The acting head of the drug enforcement administration said a similar thing. Where are you on this question? And what would do you if you were president, and two top members of your administration were floating that idea?

O'Malley's response was as follows — despite ending by stating "black lives matter," he didn't actually directly answer Dickerson's question about Comey's remarks, or about the validity (or lack thereof) of the "Ferguson effect."

John, I think the -- I think the call of your question is how can we improve both public safety in America and race relations in America, understanding how very intertwined both of those issues are in a very, very difficult and painful way for us as a people. Look, the truth of the matter is that we should all feel a sense of responsibility as Americans to look for the things that actually work to save and redeem lives, and to do more of them, and to stop doing the things that don't.

For my part, that's what I have done in 15 years of experience as a mayor and as a governor. We restored voting rights to 52,000 people. We decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana. I repealed the death penalty. And we also put in place a civilian review board. We reported openly discourtesy, and lethal force and brutality complaints. This is something that -- and I put forward a new agenda for criminal justice reform that is informed by that experience.

So as president, I would lead these efforts, and I would do so with more experience and probably the attendance at more grave sites than any of the three of us on this stage when it comes to urban crime, loss of lives. And the truth is I have learned on a very daily basis that, yes, indeed, black lives matter.

Bernie Sanders

Next, Dickerson turned to Sanders, referencing a story told to him by one of and unnamed colleague of Sanders' in the U.S. Congress.

Senator Sanders, one of your former colleagues, an African- American member of Congress, said to me recently that a young African- American man had asked him where to find hope in life. And he said, "I just don't know what to tell him about being young and black in America today." What would you tell that young African-American man?

Considering some of the criticism Sanders has absorbed over his racial justice rhetoric — specifically, his habitual framing of economics at the center of questions about race — his response was pretty on-point. Namely, he specifically cited the need to hold the police accountable for their actions.

Well, this is what I would say, and the Congressman was right. According to the statistics that I'm familiar with, a black male baby born today stands a one in four chance of ending up in the criminal justice system. Fifty-one percent of high school African-American graduates are unemployed or underemployed. We have more people in jail today than any other country on earth. We're spending $80 billion locking people up, disproportionately Latino and African American.

We need, very clearly, major, major reform in a broken criminal justice system. From top to bottom. And that means when police officers out in a community do illegal activity -- kill people who are unarmed who should not be killed, they must be held accountable. It means that we end minimum sentencing for those people arrested. It means that we take marijuana out of the federal law as a crime and give states the freedom to go forward with legalizing marijuana.

Hillary Clinton

Finally, the issue of racial justice came around to the race's current frontrunner, Hillary Clinton. Dickerson asked her a slightly different question than the prior two, asking her about her strategic views on policy versus activism.

Secretary Clinton, you told some Black Lives Matter activists recently that there's a difference between rhetoric in activism and what you were trying to do, was -- get laws passed that would help what they were pushing for. But recently, at the University of Missouri, that activism was very, very effective. So would you suggest that kind of activism take place at other universities across the country?

Clinton's response was typically cagey — she didn't actually get much into the realm of policy, instead citing her youth as a politically minded college student, and detailed how she met with mothers of slain children, whether by the police, by racist aggressors among the general public, or gang-related violence.

Well, John, I come from the '60s, a long time ago. There was a lot of activism on campus -- Civil Rights activism, antiwar activism, women's rights activism -- and I do appreciate the way young people are standing up and speaking out. Obviously, I believe that on a college campus, there should be enough respect so people hear each other. But what happened at the university there, what's happening at other universities, I think reflects the deep sense of, you know, concern, even despair that so many young people, particularly of color, have...

You know, I recently met with a group of mothers who lost their children to either killings by police or random killings in their neighborhoods, and hearing their stories was so incredibly, profoundly heartbreaking. Each one of them, you know, described their child, had a picture. You know, the mother of the young man with his friends in the car who was playing loud music and, you know, some older white man pulled out a gun and shot him because they wouldn't turn the radio down. Or a young woman who had been performing at President Obama's second inauguration coming home, absolutely stellar young woman, hanging out with her friends in a park getting shot by a gang member.

And, of course, I met the mothers of Eric Garner and Tamir Rice, and Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin and so many of them who have lost their children. So, your original question is the right question. And it's not just a question for parents and grandparents to answer. It's really a question for all of us to answer, every single one of our children deserves the chance to live up to his or her god-given potential. And that's what we need to be doing to the best of our ability in our country.