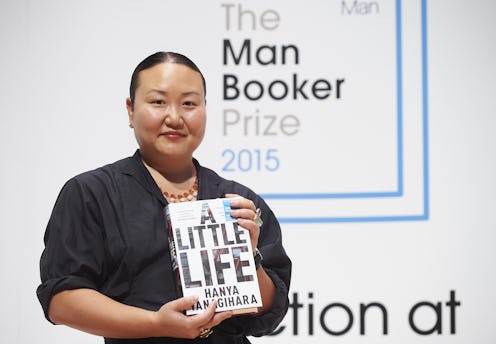

New York Review of Books critic Daniel Mendelsohn excoriated the Booker-nominated novel A Little Life, likening its "guilty pleasures" to "a teenaged rap session." Now author Hanya Yanagihara's editor has hit back with a letter to the NYRB editor. Doubleday's Gerald Howard defended Yanagihara and her novel from the Goldfinching critic's assertion that A Little Life "duped many into confusing anguish and ecstasy, pleasure and pain" with its treatment of protagonist Jude.

Mendelsohn's claims that Yanagihara has "duped" her readers stem from his opposition to the abuse Jude endures throughout his fictional life in this ugly world. The argument is that, to read about such torment, any reader cannot help but feel emotional attachment to the character's situation. This, he believes, is fraudulent storytelling.

In his letter to the editor, Howard reminds Mendelsohn that "art is at the bottom of an elaborate con game," one designed to give us emotional and aesthetic experiences that "justif[y] the con." He asks, referencing a handful of male authors writing about difficult character experiences:

When I have felt like crying while reading a novel by Charles Dickens (take your pick) or, to cite a book in a wildly different register, John Williams’s Stoner, have I been “duped” by those authors? If so, I look forward to being duped in similar fashion many, many times in the future.

Mendelsohn asserts in his answer to Howard that "Yanagihara achieves her effects dishonestly" by giving Jude a hard life. In an attempt to discredit Howard's stance, Mendelsohn reminds Howard of his own quote in Kirkus piece, in which the editor expresses his discomfort with Yanagihara's treatment of her protagonist Jude: "This is just too hard for anybody to take."

But the critic's reply does not hold up to the undressing Howard gives him. Howard's concerns with A Little Life appears to be the same as Mendelsohn's, on a fundamental level. However, the difference lies in the two men's disparate treatments of the issue: Howard argues that Jude would break underneath the events of his life; Mendelsohn claims that the author has somehow "cheated" or "pandered to" her readers with her abuse-survivor protagonist.

In what might appear to be a winning zing, Mendelsohn expresses his "wishes that [Howard] had imposed as stringent an editorial oversight on his author as he would do on her reviewers." But the sting of this jab disappears in light of one statement from Howard — made, rather ironically, in the very Kirkus article the critic pulled out in his own defense.

As he recounts his experiences editing Yanagihara's novel, Howard mentions that the "[o]ne thing you better get used to as an editor is losing these arguments" over which passages to cut from a manuscript. He then observes: "I lost a whole lot of them with David Foster Wallace when I was working with him, and that worked out pretty well."

Mendelsohn's omission of this statement — his refusal to compare Howard's experiences with both writers, Yanagihara and Foster Wallace, even in passing — is unsurprising. This, after all, is a critic who believes "young people are increasingly encouraged to see themselves not as agents in life but as potential victims." His foregoing a crafted argument in favor of testy one-liners is all we can really expect.