News

The Major Problem With Wrongful Convictions

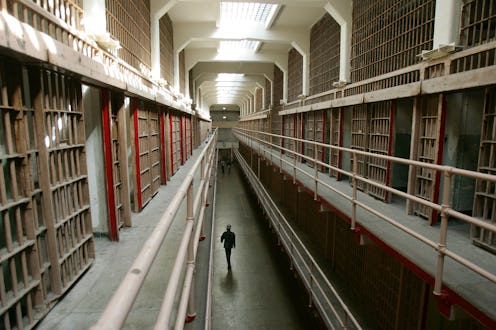

The hit Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer has made viewers skeptical of America's criminal justice system and concerned about men and women wrongfully convicted of felony offenses. The show's main subject, 53-year-old Steven Avery, was convicted of a violent sexual assault in 1985, but was exonerated by DNA evidence in 2003, after spending 18 years in prison. Because people who spend time behind bars for crimes they didn't commit are robbed of those years, it makes you wonder what states do for the wrongfully convicted once they're exonerated and released.

In case you're Netflix-less or forgot the early details in your rush to finish the series, Avery was freed after DNA technology proved that a hair found on the victim didn't come from him, but from Gregory Allen, a man already convicted of sex crimes who looked similar to Avery. The series then follows Avery as he's accused and convicted of a 2005 murder, which he claims he also didn't commit.

When Avery was released in 2003, Wisconsin law only allowed a maximum of $5,000 per year in prison or a total of $25,000 to be paid to those wrongfully imprisoned, and the state still has the same standards today. In December, the state assembly and senate held hearings for a bipartisan bill that would increase compensation to $50,000 per year, with a maximum of $1 million, and also provide health care for exonerees.

Wisconsin isn't the only state that currently offers minimal help for those wrongfully convicted. According to the Innocence Project, 20 states don't have any compensation statutes on the books. People in Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Wyoming aren't entitled to anything if their name is cleared.

The Innocence Project, which helped get Avery exonerated, writes on its website:

Deprived for years of family and friends and the ability to establish oneself professionally, the nightmare does not end upon release. With no money, housing, transportation, health services or insurance, and a criminal record that is rarely cleared despite innocence, the punishment lingers long after innocence has been proven. States have a responsibility to restore the lives of the wrongfully convicted to the best of their abilities.

With no guaranteed help, exonerees often have to sue a state or city in order to get the money to rebuild their lives, which forces them to enter lengthy lawsuit and court proceedings. This also means that they could be without a place to live or basic necessities when they get out of jail, as money from a lawsuit wouldn't be in their possession for months or years.

Even many states with existing compensation laws fall short, failing to provide heath care, counseling, affordable housing, or assistance in reentering the workforce. The Innocence Project also points out that many deny payments to people who "contributed" to their own wrongful conviction by confessing or pleading guilty to the crimes they were empirically proven to have not committed, whether they were coerced or not. Additionally, some exonerees are denied because they have previous, unrelated felonies. If passed, Wisconsin's bill would be a major step toward adequately assisting people who are wrongfully convicted. But the rest of the nation has a ways to go, as compensation laws — or a lack thereof — differ widely from state to state.