1990: I am five years old, and David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” is playing on the radio. I am in the car with my father, who explains the story of the song to me: It’s a conversation between an astronaut in space and the people in the control room on Earth, but then the astronaut goes “space crazy" and chooses to drift off into eternity.

This is a thing my father does often — explain the stories told in songs, particularly the tunes that play on our local classic rock station while we are in the car driving somewhere. The stories are how he introduces my brother and me to new music: He shows us the Beatles movies Help!, A Hard Days’ Night, and Yellow Submarine; he and my mother take us to see the musical theatre version of The Who’s Tommy when the touring production arrives in Boston; he tells us about the context for Pink Floyd’s “The Wall, Part 2,” which my brother and I mostly like because of the inclusion of the children’s voices. (We are forbidden from watching the movie of The Wall until we are much older). After the success with “The Wall,” he attempts to play “Dark Side of the Moon” for us, but the unhinged laughter at the end of the track terrifies me and I make him turn it off. It will be roughly 10 years before I revisit it.

Starting with Bowie, my father and I will continue to share music throughout my entire life. He plays the guitar for me regularly, until he develops carpal tunnel syndrome and has to stop; then I start playing the piano for him instead. We trade new bands as we stumble upon them — Dream Theater, The Decemberists, and more — and sometimes, when my father picks me up from school, heavy guitar riffs can be heard from the car as I open the door. “Your dad listens to that?” my classmates say in awe.

There are two common themes in the music we share: The relative complexity of it, and the fact that it is so frequently story-driven.

I will spend my life as a storyteller, although the medium in which I operate will change repeatedly as the years go by. But this is the beginning: Bowie and my father teach me that stories can be told however you want them to be, and in whichever way you see fit.

1998: I am 13 years old, and Jakob Dylan’s band The Wallflowers covers Bowie's “Heroes” for the soundtrack to the Roland Emmerich Godzilla movie starring Matthew Broderick. The movie is not remembered fondly, but the song plays frequently on the radio. This is a time in which I still listen to the radio, mostly as an attempt to “fit in.” Looking back as an adult, I realize the irony in the situation: A Top 40 radio station geared exclusively towards popular music incessantly spinning a re-do of a song by Bowie, an artist who spoke so strongly to people who didn’t fit in.

That was me — someone who didn’t fit in, but tried hard to do so anyway. I was never bullied — or if I was, I simply didn’t register it — and I had friends, but I was far from popular. I was kind of a weird kid; I grew into a weird adult, too, but I’m at peace with my weirdness now (it’s actually one of the things I like most about myself). But in my pre-adolescent and teen years, I was aware that I was weird, and aware that weirdness was socially undesirable. I had unruly hair and big glasses and braces, and I was short; I was interested in nerdy things at a time when “geek chic” hadn’t yet become de rigueur. I was uncomfortable in my body, and rarely felt “pretty” — “pretty,” of course, being a Thing Girls Were Supposed To Be. I tried to be tough instead, outfitting myself in combat boots and black t-shirts and red bandanas. I rarely wore dresses or skirts, and I put up a fight whenever I had to dress “nice” for something.

The one time I asked my mother to take me shopping at a popular clothing store that was the place from which to fill your wardrobe, she humored me, and I walked away with items that looked like The Things People Wore. When I wore them, however, they felt like a costume — and I didn’t feel at home in it. My combat boots and black t-shirts and red bandanas were costume pieces, too, but at least they felt like something I could live in. So I left The Things People Wore hanging in the back of my closet and ignored them.

I regret this venture — not the ignoring of the clothes, but the acquisition of them in the first place.

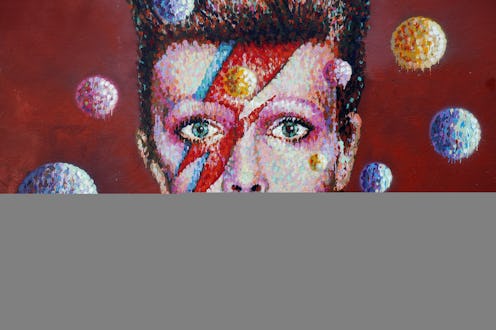

But that was why we had Bowie. Bowie was for the oddballs. Bowie was for the people who felt like they were performing all the time. Bowie created characters, costumed them, made them live and breathe, and made it OK to try on different identities. Bowie had a realistic idea of fame — that is, that it “doesn’t really afford you anything more than a good seat in a restaurant.” Bowie’s music said, you think you’re weird? Well, we’re all weird, so come on in, the water’s fine.

So perhaps the whole “Heroes” thing makes more sense than I’d initially thought. Godzilla tried so hard to fit in, outfitting itself with snazzy special effects and a Top 40 soundtrack, but ultimately, it never quite got there.

And you know what? That’s OK.

The Early 2000s: Sometime in high school, I realize I don’t hate disco music. I mean, I don’t actively seek it out — but I don’t mind it terribly much if I happen to encounter it in the wild . I make this discovery when I observe that the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive” is actually a pretty decent song. My dad agrees with me, and reminds me about Bowie’s “Fame.” “That’s technically a disco song,” he tells me, before blowing my mind with the fact that John Lennon worked on the tune with Bowie. (In a pre-Wikipedia era, this kind of trivia is much harder to come by.)

This is when I realize that, contrary to my previously held belief (and yes, I know now how pretentious this belief was — ah, the callowness of youth), just because something is popular doesn’t mean that it’s mindless. Working within a familiar frame, there’s still plenty of room to play; it is possible to make something that has both popular appeal and artistic merit. Bowie did it all the time; it's one of the things that made his work so successful.

This is one of the most important lessons about art that I will ever learn.

The Mid-2000s: I am in college in New York, and for the first time in my life, I do fit in. More important than that, though, are the people I fit in with. We share interests, but are also diverse enough to broaden each other’s horizons. We are patient with each other, and kind, and generous. These are friendships unlike any others I have ever had, and they will remain some of the most important relationships in my life.

We have a fondness for cheesy ‘80s fantasy movies, and we watch Labyrinth together repeatedly, Bowie-as-Jareth the Goblin King’s codpiece a never-ending source of amusement. He is our mascot. While bopping along to “Magic Dance” during one such viewing, one of us solemnly looks at the others and intones not “Dance, magic dance,” but “Pants, magic pants.”

She is still one of my closest friends, and my phone still rings with “Magic Dance” whenever she calls me.

2006: I am 20 years old, and studying abroad at a drama school in London. The soundtrack to these six months of my life is The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust — already my favorite Bowie album, but given new meaning, with new memories draped off of each song, as my flatmates and I drink in everything the city has to offer. I go clubbing in London — not a thing I ever do in New York — but the kinds of places we go dancing are the kinds of places that play Bowie. In the months prior to my arriving in the UK, I had begun to feel stagnant, both as an artist and as a person; in London, I learn how to risk again. All the children boogie, so to speak, and this is the most confident I will ever feel in my life.

Late 2006 – Early 2007: I am 21 years old, and I find a Bowie t-shirt somewhere — one from the era of The Man Who Sold the World. I wear it frequently. I still have it; it’s one of my favorite articles of clothing. It is not a costume.

2015: I am 30 years old, and thanks to its prominent inclusion in the soundtrack for Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, “The Man Who Sold the World” can be heard frequently in my partner’s and my home.

I am no longer working in the theatre, but somehow, I have become a writer. My life is good — very good — and yet I still can’t shake the feeling that I am somehow not good enough, that I have not achieved everything I should have, that I am a disappointment. I know there is term for this feeling — “imposter syndrome” — but knowing about it does not make it any easier to cope with.

“The Man Who Sold the World” makes more sense to me now than it ever has before.

January 11, 2016: I will be turning 31 in two months, and I’m in the shower. My partner, with whom I am now planning a wedding, pokes his head in the door and says, “Brace yourself for bad media news.” “What happened?” I ask. “David Bowie died,” he replies.

I am not surprised. Many of the artists I have long since admired in many different arenas — music, film, theatre, television, literature — are officially Old, and since no one lives forever, many of them are now dying. But although I am not surprised — and, indeed, have almost come to expect it, given the sheer number of artists who have passed within the last year — I still feel my heart drop like a stone into the pit of my stomach.

What strikes me the most as each person passes is that they will no longer be around to create art.

People rarely like to pay artists for their work; the overarching mindset seems to be that because it is creatively fulfilling, and yet seemingly of no “practical” value, the creation of art is not worthy of monetary compensation. If artists become “stars,” then they are deemed worthy of making a living off of the art they create. It is a broken system, and it is why Bowie was frequently uncomfortable with his fame — but it does highlight one important thing: The world is better for the existence of art and artists, and if artists can survive, then they can create universes upon universes.

I think about what the world would be like without art. I think of all the beauty, and the strangeness, and the wonderfulness that simply wouldn’t exist. I think about how we wouldn’t even know what we were missing if it had never existed in the first place. I think about the people art inspires, the lessons we learn from it, the lessons we can continue to apply to our lives even if we do not make art ourselves; we would not learn these lessons without it. I think about the people with whom we would not share art if it did not exist, and I think about how such an important element of my father's and my relationship would be absent without it.

I think about all the oddballs who would never feel like there was anyone out there who understood them — who would never know whether there was life on the Mars they happened to be inhabiting.

I think about Bowie, and I’m glad that we had him for the brief time that we did.