Books

What Reading Sunil Yapa Means To Me As An Activist

I attended my first protest a week after my 19th birthday: a die-in at Abbott Laboratories — the Chicago-based pharmaceutical company which was, at the time, threatening to withhold AIDS, arthritis, and blood pressure medications from Thailand because the Thai government had expressed the desire to produce a version of their own, less expensive, AIDS medication. I stood in a plaza outside the company’s annual shareholders meeting, wearing a hospital gown and surrounded by a small group of fellow activists, medical students, and Thai citizens, and on cue I feigned dying in the street while another activist drew a chalk outline around my body. The protest appeared just once on the local news. But I was hooked. I was going to change the world.

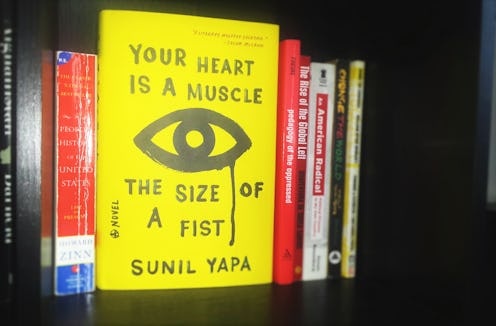

It is in a similar space of emerging activism that readers meet Victor, the central character in Sunil Yapa’s debut novel, Your Heart Is A Muscle The Size Of A Fist , published by Lee Boudreaux Books earlier this year. The novel tells the story of just one day — the November 30, 1999 World Trade Organization protest in Seattle, Washington — as experienced by seven different characters whose impossibly disparate narratives converge on one another throughout the text, as kaleidoscopically as protesters themselves.

Your Heart is a Muscle the Size of a Fist by Sunil Yapa, $9, Amazon

Victor is a homeless, bi-racial 19-year-old, squatting in a tent under a highway overpass just miles from the house where his father lives. Victor has recently returned to his hometown after three years of wandering the world, and he plans to sell pot to the WTO protesters in order to make enough money to leave Seattle again, for good. His plan goes awry almost immediately when he realizes the activists are more serious about their mission than a bunch of stoned hippies. His money-making scheme unsuccessful, Victor’s plan quickly changes, and he suddenly finds himself volunteering for one of the most dangerous roles in the entire direct action — being locked to other activists through interlinking PVC pipes as part of an immovable human blockade designed to separate the WTO delegates from their meetings.

Yapa’s other characters, in many ways, border almost on caricature — the good cop and bad cop; the idealistic protestor and the violent revolutionary; the Sri Lankan delegate desperate for his country to gain admission into the WTO and the white, upper-middle-class activist who believes he’s attended the protest to protect countries like Sri Lanka; the well-intentioned but world-weary police chief and his radical, prodigal son. But there’s truth to them. I recognize each of these characters. I’ve known them all. And I recognize parts of myself — and the selves I used to be — in more than a few as well.

Like Victor, I spent my late teens and early 20s in a fervid, answer-seeking trek across the world. I saw sweatshops in Mexico, and dug trenches for water lines in Honduras, and attended anti-globalization rallies in Brazil, and visited women-run arts and crafts co-ops in Kenya, and backpacked across Morocco at the end of Arab Spring, and protested the torturing and killing of los desaparecidos outside Fort Benning, Georgia. After college I moved into an old convent in East Los Angles, with a bunch of kids who planned to live together, work together, and change the world together — a place where I thought I could take my activism off of main street and Wall Street, and into the world I believed I might change.

“Wearing a pair of sweatshop shoes to a sweatshop protest — well, he wanted to say, what the fuck do you think you’re wearing? I wear my Nikes and they remind me I am small and the world is large and who are you to judge me for a thing like that? The world is large and I am small.” — Sunil Yapa, Your Heart Is A Muscle The Size Of A Fist

Like another of Yapa's characters, Kingfisher — a student of militant nonviolence who begins to question her teachings just as the Battle of Seattle reaches critical mass — I devoured activist literature like Manufacturing Consent and If They Come In The Morning, and still others: A People’s History of the United States, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, the Catholic Worker newspaper, and anything with Saul Alinsky's name on it. And like Kingfisher, I found myself caught in the paradox of believing so wholly in the power of direct action, while knowing from experience that all the activist theory in the world couldn’t prepare me for what I’d actually encounter in the streets — not the streets of protest, but the streets where the people I’d taken it upon myself to protest for lived. But the activists I spent so much of my time with, who were so very high from the adrenaline of marching in the street, rarely talked about what happened when a movement failed to make change.

And ultimately, like Yapa’s seasoned protester John Henry, and his Sri Lankan delegate Dr. Charles Wickramsinghe, I had little idea what to make of a world that I found so beautiful, and loved so much, but that seemed to be on the verge of imploding with all the wrongness that existed within it.

Prior to reading Your Heart Is A Muscle The Size Of A Fist I had never encountered a book that made so explicit the fact that it’s OK to be conflicted about the work one does as an activist; that it’s natural to be skeptical at times. No one had ever said to me that sometimes protest doesn’t work, sometimes direct action incites nothing but doubt in one's cause, and there will be nights when the community you’re working for so deeply breaks your heart you want to quit altogether. I thought the problem was just me — that it was my fault the world wasn't changing fast enough. All my studies had given me confidence, but no resilience; tactics, but no practical applications.

“That they felt they had the power to do something about it. That was what made it so American. That they felt they had the power to do something — they assumed they had that power. They had been born with it — the ability to change the world — and had never questioned its existence.” — Sunil Yapa, Your Heart Is A Muscle The Size Of A Fist

Because ultimately, if I’m going to be honest with myself, what sustained me through my young life of protest was the anonymity. I didn’t have to be much of anything other than, as Yapa wrote: just another “high-fructose face” lost in the horde of assembly. Nobody was looking at me in particular to do anything. I could simply march and march, and chant and chant, could believe in justice and rightness so fully my heart might have burst into pieces, and as long as enough people marched and chanted and believed alongside me, we would change the world. Maybe even Tom Morello would show up.

So when I took the lessons I’d learned in protest, and tried to apply them to the work I was attempting in the communities that I believed I was protesting for, and the world failed to change, all my once-unrelenting belief came crashing down around me. Nobody had ever laid so bare for me the complex dynamics of organized direct action quite like Your Heart Is A Muscle The Size Of A Fist did. I was only 11 years old at the time of the 1999 WTO protest, but I’d studied it in college as the greatest example of American activism in my lifetime — something to aspire to. Yapa’s depiction — one that's idealism left room to include the realities of hypocritical protesters, uncertain activists, and confused delegates — was hardly so black-and-white.

“What if they knew what a real revolutionary was? How bloody is a real revolution. He looked around, suddenly feeling the need to sit, and saw nothing but their faces, their round wet faces staring back at him. What a violence of the spirit to not know the world.” — Sunil Yapa, Your Heart Is A Muscle The Size Of A Fist

Nobody had told me that loving the world was just as important — more important — than trying to fix it. And until reading Your Heart Is A Muscle The Size Of A Fist, I didn't know that's exactly what I'd been hoping to learn all along. In school my textbooks and professors expressed the importance of anger as a stepping stone to action, to liberation — and as both a young woman and a millennial, I hear my generation critiqued for not being angry enough about our world. But anger only works if it inspires action, and for me anger, which has never been a motivating force, only led to inaction. What Yapa’s characters all have in common, no matter how different they each may be from one another, is a desperate, sustaining love for the work that they do, and the world that they do it in. Even the bad cop.

The last protest I attended (for now, anyway) was in May of 2013, an International Workers Day march in Chicago, my hometown. There, a cameraman filming clips for a Peruvian news website noticed my fair-trade African patterned skirt, my Che Guevara t-shirt, my tie-dyed bandanna, and pulled me aside, pressing a microphone into my face and asking me to tell his viewers why I was protesting that day. Because a boy I love is off fighting a useless war in the Middle East, I should have said. Because one fall my friend was gunned down in the streets of this city for no reason. Because hardworking immigrants are being deported, and 12-year-olds are being held in detention centers for years for carrying baggies of weed in their pockets, and my peers are graduating college with $100,000 in debt as Wells Fargo gets bailed out, and California is on fire, and my student health insurance doesn’t cover birth control, and every time I buy a cup of coffee I wonder how many injustices were committed between where it began in Ethiopia and my purchasing it in Chicago.

“He heard them in the streets saying, ‘Another world is possible,’ and beneath his ribs broken and healed and twice broken and healed and thrice broken and healed, he shuddered and thought, God help us. We are mad with hope. Here we come.” — Sunil Yapa, Your Heart Is A Muscle The Size Of A Fist

What I should have said was: People over profit, and si se puede, and conscientious objection, and manufactured consent, and nonviolent revolution, and the water is being poisoned, and the war won’t ever end. At the very least I could have said: I'm here because this is just somewhere to stand for a little while, in a world where I have no idea where to stand. But I was nervous in front of the camera, in front of this Quechua-speaking journalist with his impossible question and his eager face, so I adjusted my bandanna, smiled, and said the first thing that came to mind: “Because this is the greatest city on Earth.” And though I sensed that I was failing the world — yet again — with such ignorant hope, damn if I believed it; if belief was enough.

Images: E. Ce Miller