News

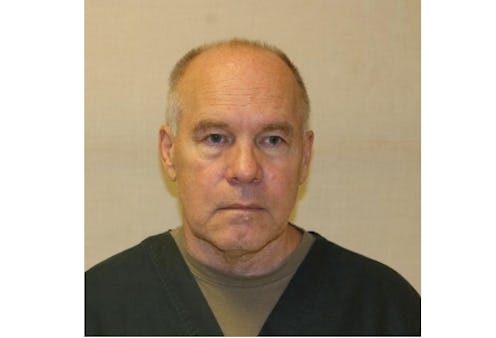

Gregory Allen Is Eligible For Parole In October

There's no question that Making a Murderer thrust Steven Avery's life into the national spotlight. But what doesn't often make it into the conversation about the Netflix docuseries or Avery is the sequence of events the documentary recounts in its very first episode. Avery's wrongful conviction for the 1985 sexual assault of Penny Beernsten, and the eventual imprisonment of the actual rapist, Gregory Allen, brings a whole new dimension to the conversation around Avery's innocence. And like the narrative around Avery's 2005 murder charge, the story of Allen's conviction isn't over yet. So when could Gregory Allen get out of prison?

The man convicted for the crime which first sent Avery to prison for 18 years is up for a parole in a matter of months. Based on information published on the State of Wisconsin's Offender Database, the Green Bay Press Gazette reports that Allen is eligible for a parole hearing beginning Oct. 24 of this year. Allen, however, is not currently serving time for the crime that originally put Avery behind bars. Allen is nearly two decades into a 60-year sentence for kidnapping and sexual assault — a crime that took place ten years after Beernsten's rape.

And Allen's criminal record doesn't stop there; the man was incarcerated several times prior to this six-decade sentence, for crimes which included violent drug-related felonies, sexual assault, and indecent exposure. So while it's unlikely any request he makes for parole will receive serious consideration, there are a few bits of information concerning the parole process that are worth keeping in mind.

Before Allen has the chance to present his argument as to why he should receive parole, a parole examiner will review his case. At the end of the hearing, the examiner will make a recommendation as to whether or not parole should be permitted. Then, once a parole hearing takes place, there is usually a wait of about 21 days before the offender receives a Notice of Action, which announces the U.S. Parole Commission Office's official decision.

If the request is denied, Allen can appeal the decision. If the appeal is denied, then he will have more opportunities for hearings later on in his sentence. But because Allen's sentence is longer than seven years, he won't be granted another such hearing until two years have passed since the previous one.

By law, the U.S. Parole Commission must grant Allen parole when he has served two-thirds of his sentence, unless it finds that he has regularly violated the rules or there is reasonable probability that he will commit another crime upon release. With Allen's lengthy history of criminal activity, there could be a long road of parole hearings ahead, with little chance of him leaving prison.