Books

What 'Radio Girls' Can Teach Us About Smart Voting

One of the more striking headlines after the British referendum read: "After Brexit Vote, Britain Asks Google “'What Is The EU?'” A vote had happened, but plenty of voters went to the polls under-informed, and now face unnerving consequences.

A fear of foreigners and the realization that a lack of good information could lead to disaster were driving forces in the programming decisions of Hilda Matheson, the BBC’s first Director of Talks, who began her tenure in 1926. As she wrote in her 1933 book, Broadcasting (the first authoritative book on the subject):

“Broadcasting and other forms of electrical communications have sprung up to meet the urgent requirements of a world which must perish unless it can devise an organization capable of expressing its human and economic unity. [Broadcasting answers] the need for rapid interchange of news and views, for familiarizing each country with the ideas and habits of all other countries, and above all the need for an education which may fit men and women, literate and illiterate, for the complicated world of tomorrow.”

Radio was almost new when Ms. Matheson took the reins at Talks, and she saw what no one else had discovered its true capacity. She wielded her wide-ranging connections and called on the top men and women in every field to come speak to the nation about their work and world events. She vetted their scripts and rehearsed them (or “bullied,” as she often put it) so that they spoke as though they were talking to a friend, rather than lecturing. This soon made Talks one of the BBC’s most popular programs, and, Ms. Matheson believed, was key to growing understanding and helping people shape informed opinions.

Her devotion to the power of broadcasting to educate and inspire led her to regularly schedule broadcasters like Vernon Bartlett, MP to the League of Nations, an institution she hoped would prevent further wars in Europe. On the passing of the Equal Franchise Act in 1928, she created Questions for Women Voters and, later, The Week in Westminster (still airing today) to provide civics lessons for freshly minted members of the electorate.

She was also devoted to free speech and exchange of ideas, regularly scheduling debates on a huge range of subjects, all in the service of helping listeners shape informed opinions.

Committed to the emphasis of fact over propaganda, Ms. Matheson wanted listeners to know the difference and be able to guard against the sway of voices railing against the dangers of foreign immigrants, among other 1920s concerns. She knew firsthand what propaganda could achieve, having set up MI5’s Rome office in 1918 and been there when, in an effort to revive Italy’s commitment to the war, they hired a brilliant journalist with a flair for propaganda named Benito Mussolini.

Seeing what had become of the free press in Italy, and knowing the power of radio, Ms. Matheson was determined to build an institution that would inspire trust. The tabloids could yowl about Bolshevism run amok, or insist Britain was right to demand heavy reparations from Germany, but the BBC, used correctly, was a tool to forge global unity. “Broadcasting may spread the worst features of our age as effectively as the best;” she wrote. “It is only stimulating, constructive and valuable in so far as it can stiffen individuality and inoculate those who listen with some capacity to think, feel, and understand.”

Her insistence on avoiding an echo chamber, building trust, and providing challenging programming was ultimately what forced her out of the BBC in 1932. The global economic downturn led to a wave of conservatism, which in turn prompted a shying away of “controversy” at the BBC. Ms. Matheson’s penchant for programming that engendered understanding of the complexities of world events and people was curtailed, right when it was needed most.

Since her time, we’ve seen a gradual erosion of trust in both experts and institutions. Propaganda, like insisting that the money Britain gives the EU would instead be given to the NHS, and that European immigrants are the source of most British economic woe, won over fact.

American media in particular can use the example of the lack of information in Brexit to heed Hilda Matheson’s lessons. Respect for expertise, for reason, for fact can inform the public and prevent short-sighted catastrophe. She saw in 1933 that “If we have the sense to give [broadcasting] freedom and intelligent direction, if we save it from exploitation by vested interests of money or power, its influence may even redress the balance in favour of the individual.” We’d do well not to forget that.

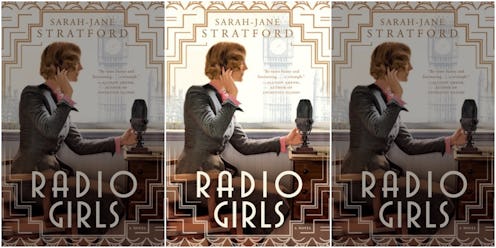

Sarah-Jane Stratford is the author of Radio Girls, a fictional account of Maisie, an American girl who lands a job as secretary at the British Broadcasting Company, where the use of radio has just begun to become popular. Hilda Matheson, her boss, helps Maisie find her talent, passion, and ambition. The two women also find themselves caught up in a conspiracy — and the use of radio can help them spread the true story.