Life

The Times Square Kiss Woman Has Passed Away

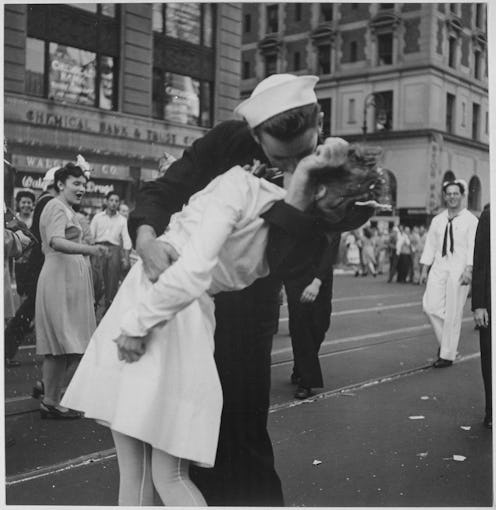

You may not know her name, but you’ve certainly seen her picture: Greta Zimmer Friedman, who passed away Sept. 8 at the age of 92, was said to have been the woman famously kissed in Times Square in 1945, a moment captured in one of the most famous photographs in history, Alfred Eisenstaedt’s “V-J Day in Times Square.” If you don’t recognize the title, you’ll surely recognize the image: Taken on Aug. 14, 1945, the photograph shows a young woman in a white uniform being soundly kissed by a sailor in Times Square, in celebration of “Victory Over Japan Day,” the day that Japan surrendered to the United States, effectively ending World War II. The photograph has since become an iconic symbol of jubilation at the end of the war.

There are two versions of the kiss photo. The most famous is the one by Eisenstaedt (pictured below), though there was another taken from a slightly different angle by Navy photojournalist Victor Jorgensen (above). A full page of the Eisenstaedt version appeared in Life shortly after being taken, and as the photo rose in fame, so did speculation about whom the two “kissers” were. (Neither Eisenstaedt nor Jorgensen recorded their subjects’ names.) Three different women and almost a dozen men have claimed to be the photo’s subjects. Friedman found out about the photo many years after it was taken, but when she contacted Life to identify herself, she was told that another woman had already come forward. “I didn't believe that because I knew it happened to me,” she said in a 2005 interview for the Veterans History Project. “It's exactly my figure, and what I wore, and my hair-do especially.” In 1980, Life reunited Friedman with George Mendonsa, the man suspected to be the guy in the photo (though there is continuing debate about that), in Times Square.

Although some people mistakenly assume that the photo shows a reunion between sweethearts or an otherwise passionate moment, by Friedman’s account, the kiss wasn’t at all romantic. In the 2005 interview, she recounted leaving work as a 21-year-old dental assistant to find people celebrating: It had just been announced that the long war was over. “Suddenly, I was grabbed by a sailor,” she said. “It wasn't that much of a kiss. It was more of a jubilant act that he didn't have to go back.” She added:

I felt that he was very strong. He was just holding me tight. I'm not sure about the kiss ... it was just somebody celebrating. It wasn't a romantic event. It was just an event of ‘thank god the war is over.’

Although many women would strongly object to being manhandled by a random stranger — and there is thought-provoking conversation to be had about whether an image’s symbolic life can be divorced from the circumstances under which it was taken (and, indeed, some have argued that the photograph is less an image of joyful relief than a depiction of a physical assault) — Friedman herself seems to have taken the sailor’s behavior in stride. Speaking about Times Square on V-J Day, Friedman described a scene of intense happiness. “It was like New Year's Eve, only better!” she said. The war had deeply affected everyone, she explained:

Everyone was very happy; people on the street were friendly and smiled at each other. It was a day that everyone celebrated, because everybody had somebody in the war, and they were coming home. The women were happy, their boyfriends and husbands would come home. It was a wonderful gift finally, to end this war. It was a long war, and it cost a lot.

She also recognized why that random kiss made a good photograph. “It was a black and white shot, and as a photographer, [Eisenstaedt] just knew that he had a good picture,” she said. “It was an opportunity and that's the job of a good photographer ... to recognize a good opportunity.”

“V-J Day in Times Square” shows only a (literal) snapshot from a long, full life. The New York Times reports that Friedman was born in Austria in 1924. Her parents sent her and two of her sisters to the United States when she was only 15, due to increasingly dangerous circumstances for Jews during the Nazi occupation of Austria. Her son told the Times that his mother’s parents were killed in the Holocaust.

In the United States, Friedman had a varied career. She worked a dental assistant for a few years (the white uniform in the photo is that of a dental assistant, not a nurse, as some people suppose). She was involved in theater, designed doll clothes for a time, and took college courses over a number of years, ultimately graduating the same year as her two children. She was also a book restorer and artist.

The Times reports that, according to her son, “Friedman did not shy away from the photo or her role in it.” In her 2005 interview, she acknowledges that she was part of something “very symbolic at the end of a bad period.” She said, “[I]t was a wonderful coincidence [of] a man in a sailor's uniform and a woman in a white dress... and a great photographer at the right time.”

Image: Victor Jorgensen/ U.S. National Archives (via Wikimedia)