Life

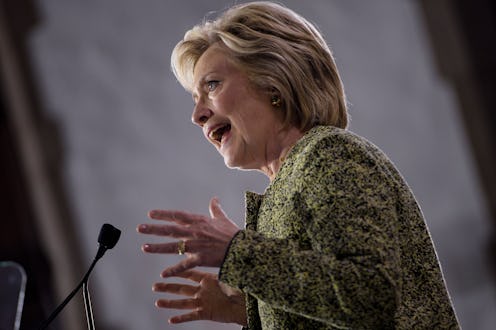

Hillary & The Psychology Of Disliking Older Women

What's age got to do with it? For Hillary Clinton, plenty. The rhetoric of age suddenly surrounded her presidential campaign pretty vociferously when it was revealed she had pneumonia; but Clinton, purely by virtue of being a 68-year-old woman who is aiming for the top job in America, is working against a lot of powerful societal prejudices against women "of a certain age." It's not a great world out there for ladies of middle age or older; the Harvard Business Review reported in March that many women in their 50s and 60s are being "forced out" of the American workforce because of preconceptions that they're no longer capable or on top of their workload. But is there any underlying societal prejudice against middle-aged and elderly women, and what's the rationale behind it?

"Old" is a very relative term, and when it comes to women it's more relative than you might think. According to a much-quoted study from 1976, people are likely to identify "transitional stages" earlier in life for women than for men; they're seen as reaching both middle age and elderly status faster (though this doesn't hold true for older women, who tend to set the ages a bit more equally).

At 68, Clinton is facing the idea of "elderly" more than Trump (though she is younger than him, and he would actually be the oldest president ever elected) because of preconceptions about female age. But age in and of itself isn't necessarily the issue. For women in Western society, the notion of aging women is historically not one that's been met with great relish, and distaste for Clinton on those grounds has a very, very long history. Let's look at the conditions that have created the idea that women over 50 are over-the-hill, disgusting, or generally a bad idea.

Western History Has Been Unkind To Aging Women

A large part of our societal distrust for, or simple ignoring of, middle-aged and elderly women is cultural. I've discussed the plight of middle-aged and elderly women in Western art and history before, but you can sum it up pretty clearly: it's not entirely kind. The ancient Greeks thought old women ridiculous and fearful figures, and many other cultures followed suit. For every depiction of elderly women as wise or benevolent, characterizations of them as unsightly hags, gossips, threats to society, and burdens to families abound. (And even wise-woman status was no protection against the stain of reputation; elderly women who lived outside the boundaries of families and had herbal knowledge were highly likely to be targeted as witches in certain periods of medieval European history.) We may believe we're all modern and enlightened folk, but cultural roots go down a long way.

The crucial role of women over childbearing age in many cultural folkloric traditions, from Japanese to Russian, is often noted by scholars; and, notably, they're often villainous or threatening. The expert Maria Tatar told NPR that it was "quite dreadful," but that evil characterization was often paired with power. Baba Yaga and her ilk are, in other words, fearful figures because of their survival ability and potential for havoc. Many of us bear ancient cultural histories of middle-aged and elderly women as terrifying, humorous, dangerous or difficult to please. And popular imagination has not fully replaced these models of women of a certain age with more nuanced pictures. The line between Hillary Clinton and Baba Yaga is, regretfully, much shorter than it really should be.

We Perceive Women As Losing Value After Menopause

Most women will be entirely aware of this phenomenon, but it's worth noting that it's been confirmed by science: a study in 2014 confirmed that the aging of male faces was seen as increasing power, while the aging of female faces was merely associated with declining attractiveness. The scientists behind it suggest that this is a part of evolutionary theory: that we're conditioned to look at aging women as less valuable because they've fulfilled their primary role for the advancement of the species, having kids, and can't do it any more. They're kaput, have no role, and therefore have no value. But part of this is surely also societal; the notion of a woman as accruing significant social power has been the exception rather than the rule in many societies throughout human history. Without precedents that identify an aging female face as the face of a potential president, we may not tie it to power.

The power of this devaluation shouldn't be underestimated. In Jean Lau Chin's The Psychology Of Prejudice And Discrimination, the attitude towards women past menopause in Western society is summed up as "dried up, useless, old hags." It's the "useless" bit that's interesting; women who could no long bear children or do as much effective manual labor because of increased age are seen as having little societal utility. This is, obviously, complete nonsense, but it doesn't stop it being powerful.

Interestingly, the loss of value doesn't uniformly create negative perception problems. Research in the UK, U.S., Sweden and China find that young people often have quite positive views of older people in general, particularly older women, perceiving them as "warm, sincere, kind, and motherly." And this may be an issue for Clinton: if what we value in older women is motherly charm rather than attractiveness or societal utility, her perception as highly competent, driven and capable of running a country rather than giving everybody hugs and tea goes against the grain, and makes us value her less.

Hillary Isn't Grey For A Reason

An interesting element of the obvious-female-aging debate is hair: women's grey hair, specifically. Notably, Clinton's husband Bill is white-haired and has been since before he was first elected president. Clinton, meanwhile, despite being 68 and thoroughly deserving a few hard-earned white hairs, rocks a beautiful blonde on the campaign trail. (Interestingly, so does Trump, who at 70 is equally prone to grey hairs; as we'll see, this may be a mistake when it comes to looking distinguished as a male candidate.) The famous British historian Mary Beard, who mounted a documentary called Glad To Be Grey after sustained abuse about her own white locks, pointed out something astute about the tie between this obvious signal of age and perceptions of competence. “It goes back to well-mown issues where the white-haired craggy male talking about politics on [TV] is fine, whereas the wrinkled, white-haired lady isn’t. With men the signals of aging suggest authority, but with women they don’t," she said.

It is intriguing that some of the most powerful women in Western political history have chosen to remain non-grey throughout their extensive careers. Madeline Albright (pictured), Margaret Thatcher, Michelle Bachelet and others among the most elite political cohort have remained elegantly colored rather than venturing into the arena of white hair. Our associations between white hair and the competence of candidates may be, superficially, undermining our perceptions.

Clinton's age may not work against her in some areas; it's been discovered that women's voices as they age are perceived to carry more authority, because they drop in pitch. But as a presidential candidate, she's not just fighting a glass ceiling for women in general; she's also dismantling prejudices against women who are middle-aged and older, whose value has diminished in the eyes of the world.

Images: Bernardo Strozzi; Bustle; QuickMeme