With award-winning photographer Substantia Jones of The Adipositivity Project, Bustle is launching A Body Project. A Body Project aims to shed light on the reality that "body positivity" is not a button that, once pressed, will free an individual from being influenced or judged by toxic societal beauty standards. Even the most confident of humans has at least one body part that they struggle with. By bringing together self-identified body positive advocates, all of whom have experienced marginalization for their weight, race, gender identity, ability, sexuality, or otherwise, we hope to remind folks that it's OK to not feel confident 100 percent of the time, about 100 percent of your body. But that's no reason to stop trying.

A '90s playlist is ringing through the background, classic Jennifer Lopez and Christina Aguilera almost draping through the room. The sounds seem like the perfect accompaniment to Jacob Tobia, genderqueer advocate, writer, model, and host of NBC OUT's Queer 2.0 series. If '90s pop music was a manifestation of all things scandalous, kitschy, and sparkly, then Tobia — with their infectious laugh, boudoir-like violet robe, and bedazzled accessories — is the decade's revival incarnate.

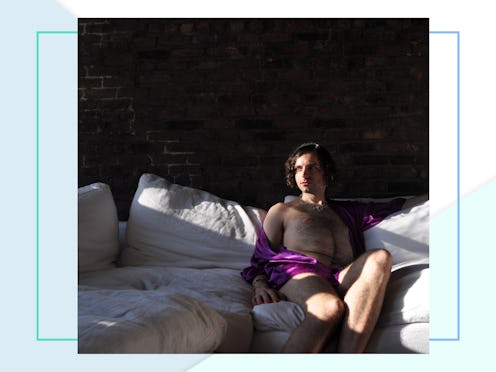

As the songs change, so does Tobia. They glide in front of the camera, experimenting with posing in a swing, beneath a furry rug, and in basic Jockey briefs alone. It's only their pink lipstick, stilettos, and jewels that remain constant.

Through it all, Tobia is striking to watch. The femininity of their movements, their choice of accessories, and their perfectly curled mane juxtaposes quite intensely with their body hair, which is thick, unapologetic, and tangibly masculine. Watching them is like watching binaristic ideas of gender decompose. They are not a boy, they are not a girl, they just are. And their body hair, in particular, feels like the perfect demonstration of that.

After the shoot, Tobia tells me that as an early bloomer and an Arab American, they began developing leg hair by the fourth grade, well before their peers. "It's funny, because since I was tall and hairy, I had the most traditionally masculine body of anyone in my elementary school class," they say. "But I was also the most feminine boy in my class by a long shot."

Despite being "femmey and a sissy," Tobia thinks it was their typically masculine physiology that most protected them from being bullied. But even if their body hair did act as a kind of shield on the playground, it became a more complex reminder of their identity as the years went on — a memento of their otherness.

"As soon as I started wearing skirts and heels, I had cis guys, cis girls, and trans people alike coming up to me and asking me why I didn't shave my legs," they tell me. "'You have great legs,' they'd say, 'But have you ever thought about shaving them?'"

Even if meant as compliments, such comments made something very clear to Tobia: "I could be so beautiful, so handsome if I would only conform to one end of the gender binary. If I 'fully' transitioned, got on hormones, and perhaps pursued surgical options, I could be a beautiful woman. Or, if I just butched it up a bit, cut my nails, and kept it consistently masculine, I could be a handsome man."

Sociocultural dogma, at large, still dictates that femininity and masculinity are neatly package-able concepts. The former often translates to dresses and frills adorning delicate features, clean-shaven bodies, and Eurocentric beauty representations, while the latter is reserved for the broad-chested, body hair-rocking, machismo-proclaiming dudes of the world. If you don't fit into such boxes, however, Tobia believes that achieving self-love has to start with a process of unlearning.

"We have to unlearn the lies that the world has told us about our bodies and ourselves," they tell me. But it's not always simple. For Tobia, this meant reevaluating not only their own body, but those of the people they are attracted to and the reasons behind their attraction. "In exploring my own desires, I've found that so many of them are based in body negativity and internalized transmisogyny, so I am trying to relearn how I am attracted," they add. "How can I ask others not to sexually neglect femmes if I can't learn to love other femmes too?"

Having a foundation of self-love can make all the difference when growing more tolerant and open-minded about the beauty of others, though. For Tobia, learning to love their body hair was about learning to let go of their gender dysphoria and their feeling of unease regarding owning their femininity while in a masculine body. One particular tool on this journey was actually getting rid of their dating apps, particularly Grindr.

"On gay dating apps, transmisogyny is everywhere and femme shaming is a daily routine," Tobia explains. "I realized that, if I were ever to love myself, I had to get out of the Grindr scene. It's a terrible app that hurts so many people and tells us that we're ugly, that we should be ashamed of our bodies."

This is not to say than Tobia has eschewed their sexuality, by any means. Instead, they have actually reclaimed it in its many incarnations. Their shoot with Substantia Jones was one expression of this. Through these images, Tobia believes they are claiming [their] right to be a sexual trans person. "I am claiming my right to have sexuality and sensuality, but to have them on my terms," they say. "I am reclaiming my body, away from the transphobic objectification that is often imposed on me. And I'm showing the world that I know I'm hot. As a gender nonbinary person, claiming my erotic selfhood and my sexuality, claiming self-knowledge of my own desirability, that is a profound action."

Tobia found great joy in capturing their "natural, authentic movement[s]" throughout the shoot, noting that learning to enjoy having your portrait taken (or taking selfies and other self-portraits) demands great levels of self-love. "You have to be able to look at the photos you've taken afterwards and be able to enjoy them, to luxuriate in your gorgeousness, which can be hard to do at first if you've grown up in a world that told you you were ugly," they tell me. Discovering little coincidences and small pleasures along the way — like their orange nails matching the orange tag on their underwear, in this case — can also make the experience just that little bit more enjoyable.

Although Tobia believes that society is generally "cycling back towards a more inclusive culture," referencing the "gender-affirming cultures [that] have already existed countless times over" in the past, this does not mean that there is still not a lot of work to do when it comes to deconstructing the gender binary at large. For them, combatting white supremicism feels like a crucial step in doing so.

"I want us to talk about the way that white supremacy, imperialism, and the gender binary go together," they tell me. "My transness and my brownness were erased by the same white masculine normativity. We can't talk about gender norms without talking about white supremacy, and we certainly can't create a body positive world without addressing both of those ideas with fervor."

Simply talking about these issues and their accompanying politics (and using our platforms online to further do so) can help. Discussing our intersectional identities — and actively celebrating those of others more marginalized to ourselves — can help. Even just reminding ourselves that our transness, brownness, queerness, fatness, hairiness, and otherness are beautiful and worthy of tolerance can help. "The more you practice affirming your beauty, the more real it will become for you," Tobia tells me. Because, sometimes, macro change starts with micro change.

Images: Substantia Jones/Bustle (8); With Editorial Oversight by Kara McGrath and Marie Southard Ospina