News

Why Voting Rights Are In Jeopardy For All of Us

You might have missed the small victory for voting rights that happened last week: Ruling that two of North Carolina’s sweeping new voter restrictions would have a disproportionate impact on people of color, the Fourth Circuit of Appeals voted 2-1 to mandate that the state allow same-day registration and out-of-precinct votes during this year’s general election. This case in North Carolina is at the forefront of today’s struggle over voting rights for minority communities. If the Supreme Court decides to take it, the challenge to the state’s harsh voter restrictions could set a precedent nationally for how the weakened Voting Rights Act will be interpreted by the courts going forward.

We need the strong protections of the Voting Rights Act, the bill congress passed in 1965 banning racial discrimination in electoral administration or voting. The statute became law following an upswell of popular activism against laws that essentially kept African Americans from casting ballots. But last summer, almost 50 years after lawmakers realized how essential this law is to our democracy, the Supreme Court decided 5-4 in Shelby Co. v Holder to negate the most effective tool in the Act's anti-discrimination arsenal: the preclearance requirement in Section 5 of the statute.

Without that requirement— which mandated that the Justice Department review any electoral changes for potential discrimination before they could go into effect — marginalized communities will have a serious uphill battle when trying to claim their fundamental rights in federal courts.

We are already seeing the impact of the Court's reckless decision. State legislatures across the country are passing laws that make it harder for people of color, the poor, the elderly, students and the differently abled to register and cast their ballots. In 2013, a conservative majority in North Carolina's state legislature deliberately waited until after the Supreme Court's decision in Shelby to push through HB 589, which would revoke or scale down the ballot access initiatives. The day after the ruling, State Senator Tom Apodaca was quite candid: "So, now we can go through with the full bill."

All eyes are on North Carolina and HB 589, which has been characterized as the worst voter suppression law seen since the Jim Crow era. If the challenge to North Carolina’s law ultimately fails when it goes to a full trial next summer, election law experts warn that more state legislators could be emboldened to follow suit across the country.

North Carolina’s story matters: It makes a textbook case for the full restoration of the Voting Rights Act.

For a state with a fraught history of voter discrimination and suppression, North Carolina had turned a corner in the past decade and made a concerted effort to expand access to the ballot for minorities through same-day registration, early voting, and out-of-precinct voting. And it worked. Although North Carolina had hovered in the bottom 12 states nationwide for voter participation for most of the 20th century, it had climbed to 19th by the 2008 election, in large part due to the new reforms.

And now North Carolina voters find themselves with an election four weeks away and little clarity as to how they will be able to legitimately cast their ballots. Thanks to Shelby and HB 589, the likelihood that some voters will be disenfranchised is high. Already with the new rules in effect during the May primary, more than 450 voters were blocked from casting ballots, according to a study from Democracy North Carolina, a nonpartisan organization that uses research, organizing, and advocacy to increase voter participation.

There is no question: If the Justice Department still had the authority to vet the state’s electoral changes in advance, North Carolinians would not be in this predicament.

Last week, North Carolina voters got a bit of a reprieve when the Fourth Circuit ordered state officials to count out-of-precinct ballots and to allow same-day registration during the upcoming election. But North Carolina has appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, which could reverse the decision and roll back voter access.

When the Supreme Court’s conservative majority effectively negated the VRA’s pre-clearance requirement in its Shelby Co. decision last summer, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg authored a biting dissent:

Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet…The sad irony of today's decision lies in its utter failure to grasp why the VRA has proven effective.

If conservative state legislatures had their way, today's forecast would be rain, rain, and more rain in North Carolina, Texas, Wisconsin, Ohio, Arkansas. Without an umbrella, the burden falls instead to minority communities — the very people who are still struggling with centuries of political and economical marginalization — to gather the resources, the advocates, and the expertise to challenge these new electoral schemes in federal courts.

These legal challenges aren’t guaranteed to be successful under a hobbled Voting Rights Act. Current lawsuits filed against electoral changes under Section 2 of the VRA, which bars any “standard, practice, or procedure” that “results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color,” are seeing only limited success.

In a brief ruling on Sept. 29, the Supreme Court allowed Ohio to cut back on a week of early voting and eliminate same-day registration this fall. Texas is awaiting a decision from a federal court as to whether or not its photo ID requirement places an unconstitutional burden on the more than 608,000 registered voters estimated not to have valid identification for this year’s vote. Wisconsin, in turn, is now scrambling to roll out its photo ID requirement in eight weeks after the Seventh Circuit gave the state the go-ahead, and the state supreme court in Arkansas heard arguments over the constitutionality of a similar photo ID law last Thursday.

But all eyes are on North Carolina and HB 589, which has been characterized as the worst voter suppression law seen since the Jim Crow era. If the challenge to North Carolina’s law ultimately fails when it goes to a full trial next summer, election law experts warn that more state legislators could be emboldened to follow suit across the country.

The legal challenge to HB 589 could have profound political implications during this year’s election especially. In a state where partisan voting patterns are increasingly racial ones, the law threatens to disenfranchise minority voters during the tight current U.S. Senate contest between N.C. House Speaker Thom Tillis (R) and incumbent Sen. Kay Hagan (D) — a race that could decide which party controls the U.S. Senate.

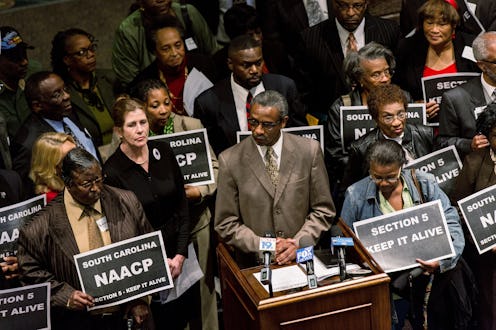

Led by the North Carolina NAACP, Advancement Project, ACLU, and other voting-rights groups, the lawsuit against North Carolina’s voter suppression law hinges on Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Plaintiffs claim that HB 589 violates Section 2 by encouraging vigilante poll monitors, instituting a strict photo ID requirement beginning in 2016 and ending same-day registration, early voting, out-of-precinct voting, and pre-registration for 16- and 17-year-olds — all of which disproportionately impact people of color.

Even though African Americans constitute only 22 percent of the electorate in North Carolina, they cast 34 percent of same-day registration ballots for new voters, 30 percent of out-of-precinct ballots, and 29 percent of ballots during early voting in 2012, according to Democracy North Carolina. More than 70 percent of African American voters relied on early voting in the 2008 and 2012 elections. Tellingly, African Americans make up 34 percent of the registered voters without an adequate photo ID.

Whether or not the state legislature or election officials are intentionally targeting African American voters with these standards, practices, or procedures is still a matter of debate. But with the cases in Wisconsin, Texas, and Arkansas slowly working their way through the courts, a cluster of contrary and opposing opinions are building up at the appellate level — any of which could spark a broad ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court on how to define Section 2. Given the unfriendly stance of the Court’s conservative majority towards robust voter protections, the celebrations in North Carolina’s voting rights community could very well be short-lived.

“History did not end in 1965,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, explaining the Court’s decision to get rid of the VRA's preclearance coverage in Shelby. The law had been designed as an extraordinary measure to counteract an extraordinary time, he reasoned, but its design had not changed to reflect the contemporary context.

I am not sure what contemporary context Chief Justice Roberts and his colleagues were thinking about in their decision. History certainly did not end in 1965. Political and economic inequities continue to disadvantage and marginalize communities of color in the U.S. today. Eight years ago — in 2006 — Congress recognized the persistence of these historical inequalities when it voted 98-0 in the Senate and 390-33 in the House to reauthorize the Voting Rights Act.

Redressing centuries of dispossession, discrimination, neglect, and violence toward African Americans and other minorities takes a proactive and serious commitment to guarding against electoral schemes that place a disproportionate burden on minority voters. Justice Roberts and his colleagues on the Court forget that the fundamental right to vote requires more of the state than the literal dispensation: "You may vote."

Our constitutionally guaranteed right to vote places a positive duty on state governments to spend resources, time, and expertise providing people of all colors, classes, genders, and abilities with equal opportunities to cast a ballot. Early voting, same-day registration, out-of-precinct ballots, pre-registration — all of these initiatives expand ballot access in ways that encourage and support the participation of all, and they should be championed.

At minimum, the voting rights struggle today demands a broad interpretation of Section 2, one that will guard against states curtailing the minority franchise. But even winning on Section 2 will not undo the disastrous legacy of Shelby. If we are truly to protect the voices of people of color in the political process, we need to mobilize a popular campaign for a full restoration of the Section 5 preclearance requirement and, in turn, for robust voter protections from state legislatures.