Books

Does Robinson's 'Lila' Live Up to the Hype?

Lila (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), the final chapter in Pulitzer Prize-winning author Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead trilogy, was released on October 7 to palpable excitement and rampant expectation. Returning to the fictional town of Gilead, Iowa, Lila entered the world like the prodigal son — delivered unto our shelves like manna from heaven, seemingly predestined to be regarded as flawless before a single book spine had been cracked.

For those of us who revel in Robinson’s spare, piercing prose and defiantly honest characters, five years has been a long time to wait, and we have grown restless. Critics also seemed barely able to contain themselves, rushing forward to anoint Lila with a National Book Award nomination after less than a week in circulation.

The storm of praise surrounding Lila was so thick, it was almost hard to find a way through the clouds. Michiko Kakutani of The New York Times called Lila "powerful and deeply affecting" on September 28, days before Brian Woolley of the Dallas Morning News declared Lila "a dark, powerful, uplifting, unforgettable novel... a great achievement in American fiction." There was also Casey Cep's widely quoted New Republic review, which declared that "Marilynne Robinson is one of the great religious novelists, not only of our age, but any age ... Not even gorgeous is a strong enough word for what grandeur charges the pages of Lila."

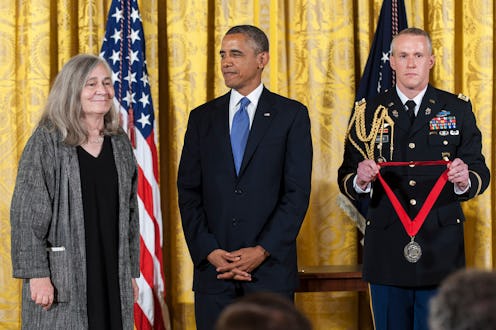

Robinson is a genius — award-winning and widely praised for the quiet, personal fiction so often overlooked in the critical marketplace. Profiles of the author bordering closely on worship litter the annals of journalism, and Robinson's students at Iowa Writer's Workshop have personally conveyed utter and complete incredulity at her staggering intellect and literary dedication.

Amidst this cyclone of critical praise and popular expectation, I turn to Lila — a slight, 262-page novel that takes up the story of the second wife of John Ames, the preacher who narrates Gilead (2004), which takes the form of a letter from Ames to his young son. How can Lila, a spindly, quiet thing not unlike the eponymous protagonist herself, possibly succeed in a world of such glaring expectations and over-ready praise? The answer offered by the text itself is delivered as swiftly and defiantly as Lila would render it in the words of her surrogate mother Doll: “Don’t want what you don’t need and you’ll be fine.”

And if there is anything Robinson does not need, it's public approval — the work, as always, speaks for itself.

Lila takes as its setting the curious space of the human mind, wandering close to stream of consciousness through a tightly wrought third-person narration. At the outset of the novel we meet Lila herself "just there on the stoop in the dark, hugging herself against the cold, all cried out and nearly sleeping," utterly unloved and alone. Through a perilous act of abduction Lila becomes the ward of the tough, self-reliant Doll, and from then until her first experience of abandonment on the steps of a church years later, Lila remains "Doll's girl." Wandering the countryside with a band of migrant laborers, Lila stays close to Doll and struggles through no small amount of pain and confusion until the crash of the late 1920s shatters what little calm she had scraped together, sending her spinning off into a shame-filled adolescence shaped by the suffering of the Great Depression.

Years later we meet Lila again, steeped in loneliness and shuddering at the margins of civilization, holed up in a shack on the outskirts of the fictional town of Gilead, nursing an irrepressible and untrustworthy longing for “the old man” of the previous novels, the preacher John Ames.

Conceived in misery, and shot through with defiant almost hostile self-reliance, Lila’s world is painted in the palette of the dust bowl itself, all greens and browns and greys with the occasional shock of color from a potted geranium or a sweet carrot straight from the ground, mousy and humble, earthy, rich and often barren. And although Robinson doesn’t privilege Lila with the first-person narration awarded John Ames in Gilead, the spiritual connection we feel with Lila as we breathe her air brings us closer, perhaps, than self-disclosure ever could; for Lila, as she repeats over and over to the adoring preacher, “don’t trust nobody.”

And yet Robinson clearly trusts her characters, leaving them raw, open, and exposed to the psychic torment brought about by the sheer act of living. Leaving the traditional conceits of plot, character and prose to swirl in the grit of the dustbowl, Robinson remains relentlessly focused on the “heroics of the soul.”

Unsurprisingly, Lila is at its best when Robinson focuses on the excruciating detail of Lila’s inner life, and the broad, sweeping questions of good and evil that shape our social narrative; such that if Robinson occasionally slips into a flowery and sentimental description when trying to squeeze just a bit to much explication out of Lila, surely she can be forgiven. Just as the reader will be forgiven for the hiccups in understanding brought about by Robinson’s forceful and exquisite manipulation of time.

As the early days and the current moment are condensed, warped, abridged, and re-aligned, Lila’s past and present are married in the rapturous revelation of personhood as it wages an ongoing war with itself. Never one to shy away from complexity, Robinson wholeheartedly embraces the imbalance this structure brings to the novel, the shuddering, shaking, tension that builds as scenes from a tortured past play out again and again, giving way only occasionally to the ecstasy of what Freud would have called a breakthrough.

Were Robinson a novelist with slightly less integrity, this narrative easily could have fallen flat, sagging under the weight of expectation — peopled by flaccid caricatures fulfilling prescriptive destinies; yet, ultimately, Robinson’s literary triumph echoes the spiritual victories of her characters, and Lila succeeds primarily because it so wholeheartedly resists our demands and holds off our inquiries. With brutal honesty and unwavering faith, Robinson travels to the bleaker realms of the human psyche in search of salvation, and brings us, if not answers, at least the comfort of hard questions.

And if I had to guess, I'd wager she hasn't even read the reviews, for whatever that's worth.