Fashion

The Fight To End HIV/AIDS Stigma In Fashion

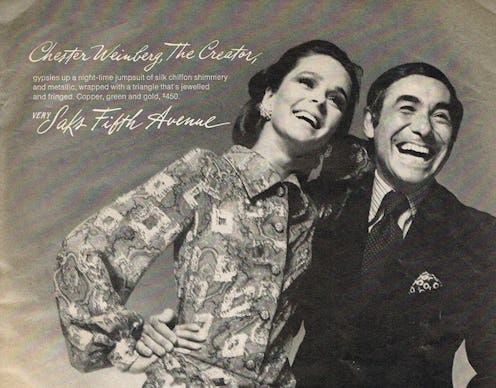

You may have never heard fashion designer Chester Weinberg's name before, but his work in the fashion industry has probably touched your life in some way. He dressed famous celebrities, was a luminary to his peers, and his name was on the tongue of the average American at a time before social media and the Internet. He mentored Marc Jacobs, Donna Karan, and Isaac Mizrahi.

You've probably never heard of Chester Weinberg because the fashion industry all but wrote him out of fashion history. As The Atlantic reports, Chester Weinberg died of AIDS on April 24th, 1985. While the fashion and beauty industries seem like extremely supportive contributors to the fight against HIV and AIDS today, it wasn't always that way. It's hard to imagine a time before things like MAC's Viva Glam campaign, Project RED, all of Kenneth Cole's AIDS initiatives, or H&M's "Designers Against AIDS" collab. But in the extremely homophobic '80s, being out as gay was considered a "liability" for fashion houses.

While a segment of the gay community has had a storied history with the fashion industry, or as "out" designer Rudi Gernreich told The Advocate, "All the good [designers], I mean the men," were gay, in the recession during the '70s and '80s, designers hid their gay identities to help their brands survive. AIDS was, and still remains, fairly mysterious to the vast majority of the population and was/is often perceived to be a "gay disease." Meaning that along with the stigma against being gay, the stigma against having AIDS — whether the designer actually had it or not — would likely follow.

Fashion publicist Barry Van Lenten told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1986, "It's the fear that nobody would want to buy a blouse or underwear because it came from a designer who, in the mind of mass America, probably stitched each of those garments with his own diseased hands."

Weinberg was considered by many to be one of Seventh Avenue's first loss to HIV, but due to the stigma and the silence around having HIV — or being gay — it's hard to know for sure how many were lost to HIV and AIDS before Weinberg's more public passing. Designer Bill Haire has said that people were sick and dying but no one wanted to address it. "They'd get sick, then they'd disappear. You'd ask, 'Where's so-and-so?' The answer would be, 'Oh, he went back to Omaha,' or 'He went back to his family.'"

It wasn't until designer Roy Halston Frowick, with all of his prestige and his high profile, passed away from AIDS in 1990 that the fashion industry was truly forced to address the epidemic in their community.

While things have certainly trended towards being more open and accepting, there are still many misconceptions about HIV and AIDS out there. I'm not just talking about the fashion and entertainment industries, but the wider realm of society as well. As a sexual health educator, I had a vague idea about what HIV was and how it was spread for most of my adult life, but until I started working at an HIV clinic, I was woefully uneducated — as many Millennials and our parents honestly are.

AIDS is still seen by many as a "gay disease," or something that only affects developing nations or the cringe-worthy pan-continental "Africa." At the worst, we see it as something that only "junkies" or "promiscuous" people get, and at best, we actually have no idea how you can get it.

In reality, HIV is a disease that affects people of all genders who have all kinds of sex with all kinds of different people. It affects people who share needles: Not just for injecting drugs, but for getting tattoos, being pierced, or injecting insulin. Whenever people come into contact with blood, breastmilk, semen, vaginal fluid, or anal fluid of someone with HIV, there is a chance that they, too, could get HIV. (Including a child in a mother's womb.)

Things have changed marginally since the death of Chester Weinberg, but we still have so much further to go when it comes to the understanding and acceptance of HIV and people living with the disease. Heck, we need more people to just understand the difference between AIDS and HIV. We need to know how to prevent it. It's not just for the legacy justice on behalf of Weinberg — it's for all people who are living with and who will die of HIV.

HIV doesn't need to be a death sentence anymore: Many people with HIV are living long lives with care and treatment. But we need to end stigma around HIV for good, as we have with many other chronic illnesses, like diabetes. Lack of access to care is an issue, especially in the developing world; but with HIV cases in North America, often people are scared to get tested or receive treatment because of the stigma surrounding even entering an HIV clinic. HIV doesn't have to be a killer, but stigma takes lives when it doesn't need to. While not all of us can be HIV researchers, stigma is something that we can all work to end.

Images: Shillmans/Flickr; Vintage Saks Fifth Avenue/Chester Weinberg; vintagedress/Twitter