Books

Shock

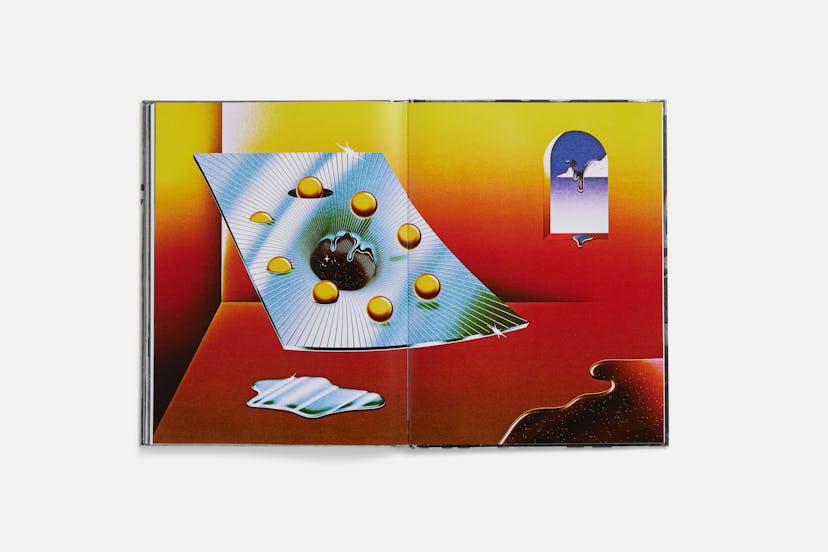

A new short story from the acclaimed author of The Collected Schizophrenias, written for A24’s companion book to Everything Everywhere All at Once.

For the companion book to their new film Everything Everywhere All at Once, directors Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert edited a collection of essays, short stories, poems, illustrations, and comics, all inspired by theories of the multiverse. Below is Esmé Weijun Wang’s story for the book — one of three original stories included in the tome that begins with the words “It was only broken in two places,” in a nod to the many-worlds hypothesis.

It was only broken in two places.

Ryder kept repeating the fact, like a poisonous mantra, as she and Charlie hurtled toward the hospital. Charlie thought he would punch his wife if she said it again, and yet Ryder kept saying it. After every instance, bringing up the notion of a still more tragic fate for their son, Charlie flinched—as an indoor kid, he had never broken a bone, but Ryder was a former gymnast. Being an athlete made life fundamentally different. Hadn’t Kerri Strug proven that in the 1996 Summer Olympics? But their twenty-year-old son wasn’t an athlete; moreover, Jonathan had jumped out of a window. That was the fundamental difference.

“He could’ve died,” Charlie finally snapped. They were close to the hospital now; he recognized the neighborhood as the one he visited to pick up Jon’s medications.

Ryder replied, “He could’ve, but he didn’t. I’m just saying that it could have been worse.”

“Very optimistic of you.”

“A broken leg will heal. He’s alive, and now he falls under the 5150.”

This was true. They hadn’t been able to force Jon into the psychiatric ward, but now that he had actively attempted suicide, he could finally be committed. Charlie’s fist loosened a fraction. He scratched absently at his face.

At the hospital’s front desk, the receptionist took their names and made calls until she reached someone who was able to report that, because Jon was still in the ER and waiting to be transferred to the proper ward, they could not see him until he was transferred.

“Is he in restraints? I know that’s why we can’t see him,” said Charlie.

“It’s fine. We’re not going to throw a shit fit about restraints.”

“What he means,” Ryder quickly said, “is that we know the drill.”

The nurse stared at them. “I’m sorry,” she said, “but that’s the policy.”

“Well, when is he going to be transferred? How are we supposed to know when he’s been transferred?” Charlie asked.

“They’ll call you,” said the nurse.

Charlie and Ryder returned to the waiting area. The land of plastic orange seats was far from full—a weekday night, Charlie supposed, would lead to fewer medical emergencies—and some of those who were waiting seemed to be in agony. An elderly man moaned to himself as he curled forward, like a tender fern, over his knees. A woman held a screaming baby to her chest. Everyone looked raw and in need of care.

“I don’t think they have our phone numbers,” Charlie said.

Ryder said, “They’ll just call our names, babe.”

“Fuck,” Charlie said, and the tears came in spite of himself. Ryder wrapped her arms around him, her hand rubbing his back in a manner not dissimilar to how she had rubbed Jon’s back when he was a baby, when she bounced him up and down in her arms. Engulfed, Charlie could smell the deodorant she used—something apricot-scented and sweet. Before they had Jon, he had never cried in public, and now, with Jon in his early twenties, Charlie had cried in public and private far more than he felt was appropriate.

Ryder, on the other hand, seemed to have hardened in response to distress. If one of them was upset, the other had to compensate by being stoic. It was an unspoken rule in their marriage, as sacred as any vow made in the Catholic church Ryder had insisted on for their wedding, and for years, neither of them had broken the covenant. But they were trapped now—calcified: Ryder was strong, while Charlie couldn’t help but crumble. Now she pulled away from him. He shrugged, embarrassed.

•

When they finally saw Jon hours later, he seemed less like their son and more like a Jon who had been eviscerated and stuffed with straw. They met in a corner of the ward during visiting hours—Charlie and Ryder had been made to wait, so as to not disturb the other patients’ routines—and Jon, their beloved, clever son, had been dulled at the edges. Charlie wanted badly to hug him, but he and Ryder had been told at the out-set that touching wasn’t allowed, so instead, Charlie clapped his hands together, soundlessly and repetitively, to give himself something to do.

“I’m sorry you had to come out here,” he said.

“No, baby,” Ryder said. Her hand rose to his shoulder, hovered, and then swiftly withdrew. “You don’t have to apologize.”

Charlie couldn’t stop staring at Jon’s leg, which was partially why it had taken so long to get him into the ward. Because of the nature of the breaks—multiple and compound—he had required surgery to implant an internal fixation device, which they would remove after six to eight weeks. It looked monstrous, with its metal scaffolding and screws. “Does it hurt?” Charlie asked, gesturing.

“My leg...” Jon slowly looked down.

He was on Zyprexa, which always made him robotic; Ryder would fight for him to be transitioned to another drug. “It’s broken.”

“It seems pretty bad,” said Ryder. Her hand came up again, and this time, she quickly squeezed Jon on the shoulder before returning her hand to her lap.

I should’ve thought of that, Charlie thought. Just be fast.

“You’ll be here for a bit,” she continued. “Until some things get straightened out. They’ll help you.”

Silence. Both Jon and Charlie were still gazing at the broken leg.

“I can’t be helped.”

“What?” Charlie’s head jerked up, as if controlled by string.

“It’s true.”

“It’s not true,” Ryder said, and her hand came up again until a loud voice asserted, “No touching,” and her hand dropped without any of them turning to look at the nurse who had said it.

“Mom’s right. You’ll get better,” Charlie said.

“No,” Jon said, “I won’t.”

•

Ryder stood at the kitchen counter, stirring her tea with a spoon. She’d used three bags of PG Tips tea to make it extra strong. She dripped honey into the cup. She had showered to get the scent of sex off. Rubbing deodorant into her armpits and blow-drying her short hair, she was still exhausted from the afternoon’s exertions, and Charlie would be home in a few hours, which required a certain amount of alertness. He would be tired and grumpy. She would cheer him up. That was how their marriage operated. It was stupid, really, to want anything else but a casual fuck now and again; like Jon, Ryder required an occasional shock in order to return her to life. Someone had told her—one of the other mothers in the PTA, someone whose name she couldn’t remember—that having Jon would be the best thing she ever did. She pressed her mouth hard to the mug’s rim. The liquid scorched her lips and she kept them there.

From the book A VAST, POINTLESS GYRATION OF RADIOACTIVE ROCKS AND GAS IN WHICH YOU HAPPEN TO OCCUR: A TRIP THROUGH THE MULTIVERSE, EDITED BY DANIEL KWAN AND DANIEL SCHEINERT. Copyright © 2022 by A24. Reprinted by permission.