Bustle Exclusive

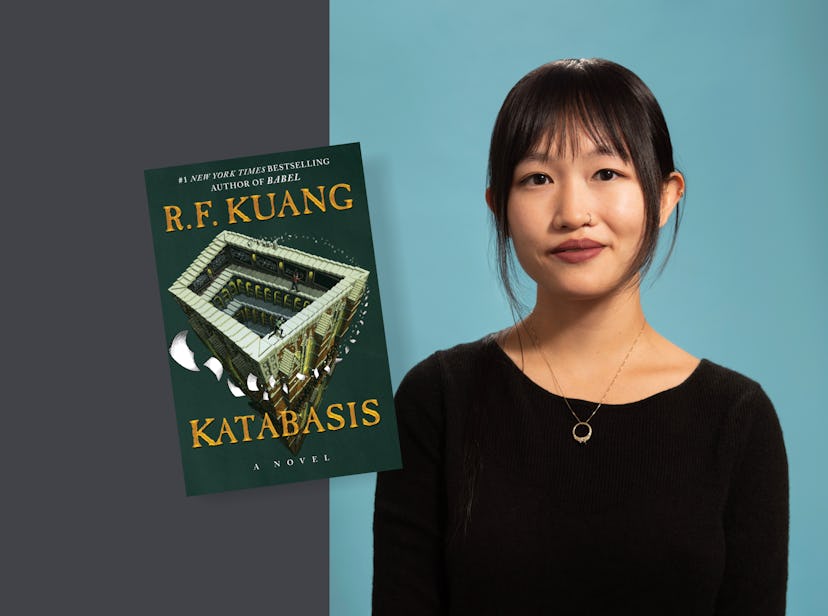

In Katabasis, R.F. Kuang Goes To Hell

Read an exclusive excerpt from the author’s new novel, in which a pair of magick students embark on a perilous journey to the underworld.

In 2023, author R.F. Kuang had literary circles and BookTok alike buzzing over Yellowface, her biting satire of the publishing industry. Two years later, she’s returning from her brief affair with literary fiction to the realm of fantasy, where she got her start with beloved novels like Babel and The Poppy War.

Kuang’s latest, titled Katabasis, follows two graduate-level magick students — Alice Law and Peter Murdoch, classmates and sometimes-rivals — as they journey into the underworld, with the hopes of retrieving their recently-deceased advisor.

Below, read the opening pages of Katabasis, in which Alice and Peter find themselves unexpectedly teaming up. To find out what happens next, pre-order the book, out on Aug. 26 from Harper Voyager.

Cambridge, Michaelmas Term, October. The wind bit, the sun hid, and on the first day of class, when she ought to have been lecturing undergraduates about the dangers of using the Cartesian severance spell to revise without pee breaks, Alice Law set out to rescue her advisor’s soul from the Eight Courts of Hell.

It was a terrible gruesome accident that killed Professor Jacob Grimes, and from a certain point of view it was her fault, and so for reasons of both moral obligation and self-interest — for without Professor Grimes she had no committee chair, and without a committee chair she could not defend her dissertation, graduate, or apply successfully for a tenure-track job in analytic magick — Alice found it necessary to beg for his life back from King Yama the Merciful, Ruler of the Underworld.

This was no small undertaking. Over the past month she had become a self-taught expert in Tartarology, which was not one of her subfields. These days it was not anyone’s subfield, as Tartarologists rarely survived to publish their work. Since Professor Grimes’s demise she had spent her every waking moment reading every monograph, paper, and shred of correspondence she could find on the journey to Hell and back. At least a dozen scholars had made the trip and lived to credibly tell the tale, but very few in the past century. All existing sources were unreliable to different degrees and devilishly tricky to translate besides. Dante’s account was so distracted with spiteful potshots that the reportage got lost within. T. S. Eliot had supplied some of the more recent and detailed landscape descriptions on record, but The Waste Land was so self-referential that its status as a sojourner’s account was under serious dispute. Orpheus’s notes, already in archaic Greek, were largely in shreds like the rest of him. And Aeneas — well, that was all Roman propaganda. Possibly there were more accounts in lesser-known languages — Alice could have spent decades poring through the archives — but her funding clock could not wait. Her progress review loomed at the end of the term, and without a living and breathing advisor, the best Alice could hope for was an extension of funding sufficient to last until she transferred elsewhere and found a new advisor.

But she didn’t want to transfer elsewhere, she wanted a Cambridge degree. And she didn’t want any advisor, she wanted Professor Jacob Grimes, department chair, Nobel Prize laureate, and twice-elected president of the Royal Academy of Magick. She wanted the golden recommendation letter that opened every door. She wanted to be at the top of every pile. This meant Alice had to go to Hell, and she had to go today.

She checked and double-checked her chalk inscriptions. She always left the closing of the circle to the end, when she was absolutely sure that uttering, and thereby activating, the pentagram wouldn’t kill her. One always had to be sure. Magick demanded precision. She glared at the neat white lines until they swam before her eyes. It was, she concluded, as good as it ever was going to be. Human minds were fallible, but hers less than most, and hers was now the only mind she could trust.

She gripped her chalk. One smooth stroke and the pentagram was finished.

She took a deep breath and stepped inside.

There was of course a price. No one traveled to Hell unscathed. But she’d resolved at the outset to pay it, for it seemed so trivial in the grand scheme of things. She only hoped it wouldn’t hurt.

“What are you doing?”

She knew that voice. She knew, before she turned around, whom she would find at the door.

Peter Murdoch: coat unbuttoned; shirt untucked; papers flapping from his satchel, threatening to tear away in the wind. Alice had always resented how Peter, who every day presented like he’d barely scooped himself out of bed, had still managed to become the darling of the department. Though this was no surprise: academia respected discipline, rewarded effort, but even more, it adored genius that didn’t have to try. Peter Murdoch and his bird’s-nest hair, scarecrow limbs balanced atop a rickety bicycle, looked like he’d never tried at anything in his life. He was simply born brilliant, all that knowledge poured by gods without spillage into his brain.

Alice couldn’t stand him.

“Leave me alone,” she said.

Peter trudged into her circle, which was very rude. One should always ask before entering another magician’s pentagram. “I know what you’re planning.”

“No, you don’t.”

“Tsu’s Basic Transportative Pentagram, with Setiya’s Modifications,” he said, which impressed Alice, since he’d only glanced briefly at the ground, and from across the room besides. “Ramanujan’s Summation with implications for the Casimir Effect to establish a psychic link to the target. Eight bars for eight courts.” A grin split his face. “Alice Law, you naughty girl. You’re trying to go to Hell.”

“Well, if you know that much,” Alice sniped, “you know there’s only room for one of us.”

Peter knelt, pushed his glasses up his nose, and with his own stick of chalk quickly etched some alterations into the pentagram. This was also very rude — one should always ask before altering another scholar’s work. But standards of etiquette did not apply to Peter Murdoch. Peter moved through life with an obliviousness that, again, was excused only by his genius. Alice had witnessed Peter spill chocolate syrup all over the master of the college’s robes at high table with no more rebuke than a shoulder clap and a laugh. When Peter erred it was cute. She had herself once spent all of dinner in the bathroom hyperventilating through her fingers because she’d knocked a bread basket onto the floor.

“One becomes two.” Peter waggled his fingers. “Abracadabra. Now there’s room.”

Alice double- checked his inscriptions and realized to her dismay that his work was perfect. She would have preferred he’d made an error that left him limbless. And she would have truly preferred that he did not then declare, “I’m coming with you.”

“No, you aren’t.”

Of all the people in Cambridge’s Department of Analytic Magick, Peter Murdoch was the last person with whom she wanted to sojourn in the underworld. Perfect, brilliant, infuriating Peter, who won the department’s top prizes at every milestone — Best First- Year Paper, Best Second- Year Paper, Dean’s Medals in logic and mathematics (which were Alice’s worst subfields, to be fair, but until she came to Cambridge she was not used to losing). Peter was one of those academics descended from a family of academics, a magician born to a physicist and a biologist, which meant he’d been steeped in the ivory tower’s unspoken rules since before he could walk. Peter already had every good thing in the world. He did not need Professor Grimes’s letter to get a job.

Worst of all was how Peter was so unfailingly nice. Always stumbling around with that blithe smile on his face, always offering to help his colleagues puzzle through hiccups in their research, always asking everyone else in seminar how their weekend had been when he knew very well they’d spent it sobbing over proofs that he could have done in his sleep. Peter never crowed or condescended, he was just guilelessly better than, and that made everyone feel so much worse.

No, Alice wanted to solve this problem herself. She did not want Peter Murdoch yapping over her shoulder the entire time, nitpicking her pentagrams because he was just trying to be helpful. And, should she return with Professor Grimes’s soul safely in tow, she especially did not want Peter sharing the credit.

“Hell’s lonely,” said Peter. “You’ll want company.”

“Hell is other people, I’ve heard.”

“Very funny. Come on. You’ll need help carrying supplies, at least.”

Alice had stashed in her bag a brand-new Perpetual Flask (an enchanted water bottle that wouldn’t run out for weeks) and Lembas Bread (stale, cardboard-y nutrition strips popular among graduate students because they took seconds to eat and kept one sated for hours. There was nothing enchanted about Lembas Bread; it was just the extracted protein of tons of peanuts and an ungodly percentage of sugar). She had flashlights, iodine, matches, rope, bandages, and a hypothermia blanket. She had a new, sparkling pack of Barkles’ Chalk and every reliable map of Hell she could find in the university library carefully reproduced in a laminated binder. (Alas, they all claimed different topographies — she figured she would get somewhere high up and choose a map when she arrived.) She had a switchblade and two sharp hunting knives. And she had a volume of Proust, in case at night she ever got bored. (To be honest she had never gotten round to trying Proust, but Cambridge had made her the kind of person who wanted to have read Proust, and she figured Hell was a good place to start.) “I’m all set.”

“You’ll still need help puzzling through the courts,” Peter said. “Hell’s very metaphysically tricky, you know. Anscombe claims the constant spatial reorientations alone—”

Alice rolled her eyes. “Please don’t insinuate I’m not clever enough to go to Hell.”

“Do you have a copy of Cleary’s?”

“Of course.” Alice wouldn’t forget Cleary’s Templates. She didn’t forget anything.

“Have you cross- checked all twelve authoritative versions of Orpheus’s journey?”

“Of course I did Orpheus, it’s the obvious place to start—”

“Do you know how to cross the Lethe?”

“Please, Murdoch.”

“Do you know how to tame Cerberus?”

Alice hesitated. She knew this was a possible obstruction — she’d seen the threat of Cerberus mentioned in a letter from Dante to Bernardo Canaccio, only she hadn’t seen it referenced in any other materials she found, and the one book that might have contained a clue — Vandick’s Dante and the Literal Inferno — was already missing from the stacks.

In fact, quite a few books she needed had kept disappearing from the library these past few months, often checked out on the very morning she’d gone in. Every translation of the Aeneid. All the medieval scholarship on Lazarus. It was like some poltergeist haunted the stacks, anticipating her project’s every turn.

“Been researching the same thing,” said Peter. “We’re too far into these degrees, Alice. No one else could supervise our dissertations. No one else is clever enough. And there’s still so much he hasn’t taught us. We have to bring him back. And two minds are better than one here.”

Alice had to laugh. All this time. Every empty slot on the shelves, every missing puzzle piece. It was Peter all along.

“Tell me how to tame Cerberus, then.”

“Nice try, Law.” Lightly, Peter punched her shoulder. “Come on. You know we’re always better together.”

Now this, Alice thought, was really laying it on thick.

He didn’t mean it. She knew he didn’t mean it because it was not true. It had not been true in well over a year, and that had been entirely Peter’s choice. She recalled it well. So how could he act so chummy, toss those words out so casually, as if they were still first-years giggling in the lab, as if time had never passed?

But then, this was Peter’s modus operandi. He was like this with everyone. All warmth and cheer — but the moment you tried to step closer, solid ground gave way to empty space.

Two bad options, then. Imperfect knowledge, or Peter. She supposed she could demand the relevant books — Peter was annoying, but he didn’t hoard resources — and figure it all out on her own. But her funding clock was ticking, and certain body parts were rotting in a basement. There simply wasn’t time.

“Fine,” she said. “I hope you brought your own chalk.”

“Two new packs of Shropley’s,” he said happily.

Yes, she knew he preferred Shropley’s. Evidence of bad character. At least she wouldn’t have to share.

She arranged her rucksack next to her feet, checking that none of the straps lay outside the pentagram. “Then all that’s left is the incantation. Are you ready?”

“Hold on,” said Peter. “You do know the price?”

Of course Alice knew. This was why scholars rarely ever went to Hell. It wasn’t that getting there was so very hard. You only had to dig up all the right proofs and master them. It was that a trip down below rarely justified the price.

“Half my remaining lifespan,” she said. Entering Hell meant crashing through borders between worlds, and this demanded a kind of organic energy that mere chalk could not contain. “Thirty years or so, gone. I know.”

But she had hardly struggled with the choice. Would she rather graduate, produce brilliant research, and go out in a blaze of glory? Or would she rather live out her natural lifespan, gray haired and drooling, fading into irrelevance, consumed by regret? Had not Achilles chosen to die in battle? She had met professors emeriti at department receptions, those poor aphasic props, and she did not think old age an attractive prospect. She knew this choice would horrify anyone outside the academy. But no one outside the academy could possibly understand. She would sacrifice her firstborn for a professorial post. She would sever a limb. She would give anything, so long as she still had her mind, so long as she could still think.

“I want to be a magician,” she said. “It’s all I’ve ever wanted.”

“I know,” said Peter. “Me too. And I — I need to do this. I must.”

A taut silence. Alice considered asking, but she knew Peter would not tell her. Peter, when it came to the personal, was a stone wall. How easily he vanished behind a placid smile.

“That’s settled, then.” Peter cleared his throat. “So maybe I’ll do the Latin, and you’ll do the Greek and Chinese.” He peered down at a segment near his right toe. “Say, why isn’t this in Sanskrit?”

“I’m not comfortable with Sanskrit,” Alice said, peeved. This was just like Peter. Condescending, even when ostensibly just asking for clarification. “I’ve done all the Buddhist sutra references in Classical Chinese instead.”

“Oh.” Peter hummed. “Well, that probably works. If you’re sure.”

She rolled her eyes. “In three, on go.”

“Right on.”

She counted down. “Go.”

And they began their chant.

Excerpted from the book KATABASIS by R.F. Kuang. Copyright © 2025 by R.F. Kuang. From Voyager, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.