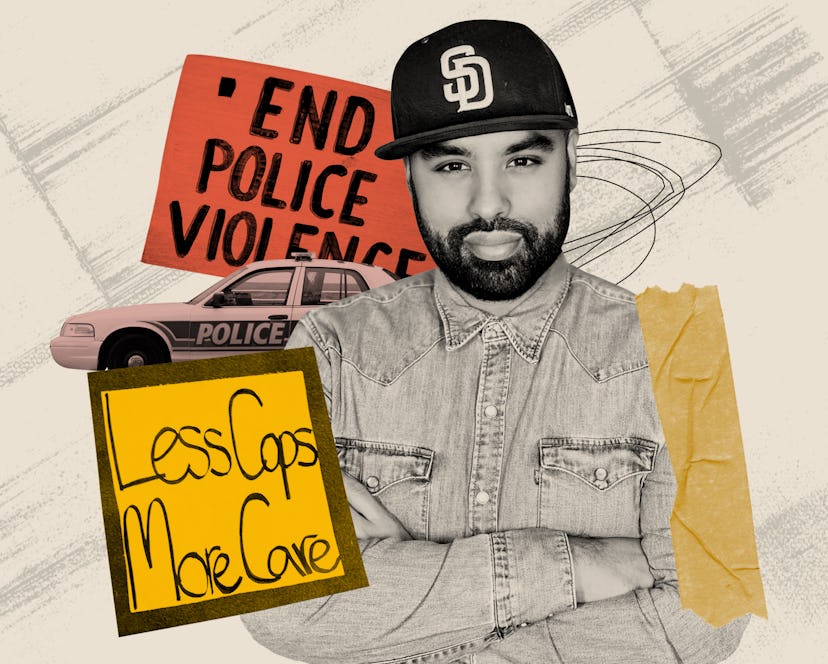

Identity

The Disheartening Way I Protected Myself Against Racial Profiling & Police Brutality

"It wasn’t only police who looked at me and were fearful."

Close friends describe me as sociable, friendly, and extroverted — but in this country, my Mexican American existence has always been perceived as a threat. By the time I was 18, I had countless traumatic experiences with law enforcement. Being racially profiled and harassed was a regular occurrence.

I was about 14 the first time I remember feeling dehumanized. I was peacefully asleep, riding in the back seat of my mom’s car with my siblings, returning home to San Diego from Tijuana, Mexico, just 30 miles away. My mom handed our passports to a U.S. Customs and Border Protection officer, who looked down at the document, then back at me. I was immediately yanked out of the car, slammed against the hood, handcuffed, and without explanation taken to secondary inspection. Hours later, officials let me go, blaming the incident on mistaken identity. My family tried to secure a lawyer, but each one turned us down. They noted that even though I was a minor, going up against an institution as tightly knit as U.S. Customs and Border Protection would be a losing case.

At 17, I was profiled during an unwarranted traffic stop. “Are you a drug dealer?” the officer asked. I said no, and he went on to ask how I was able to afford my Ford F-150 truck — a vehicle my parents helped me buy after I committed to rigorous personal saving. The cop let me go after not finding any drugs.

At 18, I was driving home from college with a friend and pulled over for a traffic violation. I remember the officer was driving in a different direction, made eye contact with me, turned his car around, and pulled me over. He approached my window with his gun drawn and screamed, “Keep your hands on the steering wheel!” I looked to my right, where a second officer was pointing his gun at my friend in the passenger seat. “Roll down the window now,” the officer closer to me said. I rolled down both windows, and the cop on my side moved his weapon about an inch from my head. He asked for my license and registration, and I remember feeling terrified that he would kill me if I reached for them. He gave me the green light to reach for my documents and eventually let us go. I remember this being the moment I went absolutely numb, realizing that life-threatening experiences with law enforcement would be something I’d have to learn to accept.

I am an openly gay man. I came out at age 18, just a few months after the police held a gun to my head. Coming out was a psychological journey, revealing an important part of who I am to the world. It presented its own set of challenges, like feelings of guilt, self-hatred, isolation, disconnection, insecurity, and overcompensation, as well as friction with friends and family and a struggle toward self-acceptance. But this part of my identity also became, for me, an unexpected shield against racial profiling and police brutality.

These became my defenses, my camouflage for my skin color — even at work.

When I was 19, I was pulled over with five friends in the car. My friend on the passenger side was extremely flamboyant. When the cops came over, they were met with my friend's exuberance and high-pitched voice. They still gave us a hard time, but I could tell they were confused and uncomfortable. I didn’t get the sense the officers felt threatened by me at all, and they let us go quickly. That moment subconsciously triggered changes that I made over the next few years to protect myself — becoming physically smaller during interactions with law enforcement, speaking in a higher-pitched tone when dealing with authority, ditching baseball caps and anything that may look “urban” while driving, and turning up the flamboyance when I felt unsafe. When I did these things, I realized police harassed me less when I was pulled over and tended to end the interaction quickly by handing me a ticket or letting me go.

It was ingrained in my mind that playing into these stereotypes would protect me, so I began to apply them to other areas of my life. This was also more of a subconscious decision at first, though over the years it almost became second nature. Looking back I now understand how harmful embodying these stereotypes was, particularly because the LGBTQ+ community also suffers greatly due to homophobia and police brutality, and historically has been disproportionately targeted by law enforcement. At the time, however, I couldn’t come up with a better way to protect myself. These became my defenses, my camouflage for my skin color — even at work. I’m in the fashion industry, where I find that the LGBTQ+ community is often welcomed, but I can’t say the same for communities of color. And although my current employer has provided an environment where my full identity is celebrated, this hasn’t been the case for most of my career.

At one of my earliest jobs, I handed my ID to a member of the human resources department and she said, “If I saw this guy walking down the street, I’d walk the other way. You look scary.” She may have meant it as a joke, but it reopened a traumatic wound. I realized it wasn’t only police who looked at me and were fearful. That implicit bias that she — and so many others — had directly affected my ability to feel comfortable at work. I found myself intentionally dressing with enough flair to ensure my sexuality was apparent at work, or consistently giving compliments to my female coworkers to seem like “one of the girls” and make colleagues less afraid of my stature.

This year has been an awakening, laying bare the ugly truth about how deep-rooted racism and bias runs through the veins of America. I also lost three men who I loved dearly, including my father. A few days before my dad passed away, my sister and I found an old documentary that he participated in when he was in high school. Even at a young age, my father was standing on the right side of history, protesting poor treatment of the Latinx population in his neighborhood.

His death was just days apart from George Floyd’s, and I couldn’t help but feel broken, knowing he spent his life fighting for the greater treatment of people of color and that decades later almost nothing has changed. As I stood by the Black community chanting, “Black Lives Matter,” I was forced to deal with my own trauma stemming from life or death interactions with cops. I hurt for the thousands of people of color who have interactions with law enforcement and live to see another day but are left mentally scarred. We need a complete overhaul of antiquated systems, supported by biased employees and police, put in place to keep Black and Brown people oppressed. My father always made sure to tell me he was proud of me. I hope he’s proud knowing that I’m using my voice to spread awareness about racial injustice and to help anyone with a similar experience understand they are not alone.

When it comes to the stats on fatal police brutality, as a Latinx gay man, I know I don’t have it as bad as most Black men or darker-skinned Latinx people, but I still get a knot in my stomach every time a police car is near or around me. In my personal experience, this country has made it clear — it accepts my gayness more than my brownness, and being gay has been a shield that saved my life. I wonder about those who don’t have something to hide behind. Far too many people of color are losing their lives due to racism and bias, and far more are living in fear that they will be the next up.