Books

This New Thriller About Two Female Scientists Studying Extreme PMS Is A Must-Read Of Summer

If there's one thing you don't see enough in books and movies and TV shows, it's the female period. Blood? Yes, you see that often — gushing out of screaming women in slasher movies or pooled around the corpses of murdered teenage girls in crime procedurals. Of course, you see blood running from the bodies of "dead girls," but how often do you see menstrual blood flowing — freely and openly — from a breathing woman with feelings and dreams and pain and repulsions and shame and love? Too infrequently.

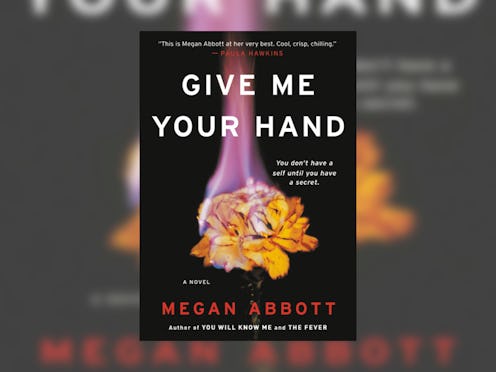

In the new novel, Give Me Your Hand, Megan Abbott writes about female blood and the havoc it wreaks upon live women through her exploration of a little-known condition known as PMDD — premenstrual dysphoric disorder, a severe form of PMS that researchers believe affects between three and eight percent of people with female reproductive systems and can lead to extreme physical pain and emotional and mental duress. ("A PMS that makes you want to die," as Broadly described it in a 2015 article.) In Abbott's book — and in real life — PMDD has been used as defense for women accused of brutal crimes, even murder.

Give Me Your Hand centers on two women — Kit Owens and Diane Fleming — both brilliant scientists and postdoctoral students who are in fierce competition with each other for two open positions with their supervisor, Dr. Severin, who has just secured a large grant to research PMDD. Unbeknownst to Dr. Severin or the other researchers, Kit and Diane have a history with one another — they were friends as teenagers, until Diane revealed a dark secret that has haunted the other woman ever since. The novel flashes back-and-forth between the present day — where a series of murders rocks the laboratory where they both work — and the past — where Diane and Kit are adolescents coping with the affects of whispered secrets and unspoken rivalries.

Give Me Your Hand by Megan Abbott, $21, Amazon

Though Kit is loosely positioned as the "hero" of the story, neither woman is blameless in the crimes that take place, and both are equally repulsed and seduced by the recognition of their baser, more brutal traits in the other. In this book, the murder isn't the mystery — the women are the mystery. They confound each other and themselves, and the conclusion of Give Me Your Hand only comes when they — and you, the reader — recognize that their outer selves badly reflect the secrets, rage, pain, and ambition that lie within them.

It's truly the beginning of the golden age of Megan Abbott: Give Me Your Hand is currently being adapted into a television show, as are two of her previous novels: You Will Know Me and Dare Me. Ahead of the publication of her newest novel, I spoke to Megan Abbott about PMDD, villains, and about the role of "dead girls" in literature — here are five things I learned:

On Why She Decided To Write About Extreme PMS

"I knew I wanted it to be about a women’s thing," Abbott tells me. "This is sort of something that plays out in The Fever, too, where it mythologizes the female body you know? That [the female body] is this anxious, out of control thing is one of my ongoing fixations. I was reading a lot about PMDD and how contested it was — and still is among some people— as a diagnosis and as a real condition. I was reading about these extreme versions of PMS and how torturous it was — especially because no one really believed them. I had to cut so much of it out because it's a novel, but I became fascinated by it all and how some people used it as a criminal defense."

On Why She Doesn't Write "Villains"

"[When I start out], I never think that there's a villain," Abbott says. "I start out with the "straight" one — the crooked one is the other one — and I sort of mess up the "straight" one and see how the crooked one is as I go. As I said, I kind of mess up Kit and give her some complications. And then Diane — who’s nearly, in many ways like an indefensible character — I throw her love. I want to give her as much sympathy from the reader as I can draw.

"But I do feel like inevitably, they do kind of become closer to the center, because we’re all pretty complicated," she adds.

On Kit And Diane's Complicated Relationship As Friends And Rivals

"There's a position — especially in movies but in books, too, like The Bell Jar — where in some ways the two women are mirror images of the other and so their experience of contrasting the other is such a complicated encounter. You’re seeing yourself projected on someone else," Abbott says. "You're seeing your own possibilities embodied in another person. I think that's a really classic female narrative... I think those are really one of the ways that women explore their own identity, and I just always fall in love with those [stories]. Or sort of like a mirror image of myself is these shards. Women look at themselves on the outside so much more than men do, and I think that’s part of it, too."

On Why This Isn't A Story About Female Friendship

Give Me Your Hand is a story of two women who have been friends and rivals, often at the same time. They have been each other's competition their whole lives, and their relationship cannot be discussed without a careful examination of their ambition, especially as two women in a male-dominated field.

"It’s the world of science, where [women are] still overlooked and underrepresented," Abbott says. "And so what does female ambition look like that in that world? I don’t consider Kit and Diane [to be] friends, by any standard of friendship," Abbott says. "But I guess it’s an easy way to describe something much more complicated, which is, as women, that we do have relationships and we may bring something out in each other — competition that’s healthy and competition that maybe isn’t so healthy. But that's what happens when there’s only one seat. It’s like, the most terrible game of musical chairs."

On Why We Need To Keep Paying Attention To The "Dead Girl" Narrative

I asked Megan Abbott about the trope of the "dead girl" in literature, television, and movies — as examined in Alice Bolin's recent essay collection Dead Girls. "All Dead Girl shows begin with the discovery of the murdered body of a young woman," Bolin writes in the book's opening essay. "The lead characters are attempting to solve the (often impossibly complicated) mystery of who killed her. As such, the Dead Girl is not a 'character' in the show, but rather a memory of who she is."

Writers like Gillian Flynn and Megan Abbott have long operated in the same spaces that have perpetuated the Dead Girls narrative but have still managed to subvert the trope by giving their female characters much of the power over their own lives. Despite this, Abbott thinks the Dead Girls trope is one with real value.

"Obviously we need many more narratives," she says. "I also think it’s an important narrative, and if we don’t unpack it and deconstruct it and subvert it, we’re never going to get the truth in it, which is, it is really about a sort of troubled masculinity. I think we’d be at a peril to not look at it closely."

She adds: "By refusing to read or watch something that has the [Dead Girl] story would be a mistake. I think you got to go in and keep writing these stories, and keep trying to take these stories apart."