News

How The Japanese Internment Camps Happened

February 19 is the Day of Remembrance, when people across the United States remember the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, a decision that was born out of fear and paranoia and led to cruelty and ruined lives. In this political climate, it's more important than ever to look at the history that created the provisions of the Japanese interment camps, which existed across the U.S. from 1942 to 1945, and had continued repercussions for the detainees that persist to this day. As we watch the arguments between the nation's courts and President Donald Trump about the refugee ban, and note Trump's own rhetoric paralleling a proposed "immigrant registry" with the Japanese camps, it's a damn good idea to have a history lesson about how America could come to deprive a significant portion of its population of their civil rights because of national background. And to have it fast.

The atmosphere surrounding the Japanese camps' creation was predicated on the attacks on Pearl Harbor in 1941, but don't let's pretend that things aren't also pretty nasty right now. (As I write, there's massive confusion about whether or not the Department of Homeland Security ever seriously considered sending the National Guard to arrest illegal immigrants).

Lest you think it couldn't happen again, here's what led up to the disgrace of Japanese internment and what we can learn from it.

Japanese Americans Were Being Targeted For Assault & Destruction By Mobs

Memoirs of the period just before Japanese internment and immediately following Pearl Harbor from those who were detained paint a picture of an extremely volatile environment in which Japanese businesses, homes, and people across the U.S. were targeted by mobs. Ashlyn Nelson, the granddaughter of a "nisei," a second-generation Japanese immigrant born in the U.S. (their parents were called "issei"), wrote for Al-Jazeera that it often exploded into physical violence:

"[My grandmother's- family's strawberry basket factory was burned to the ground by arsonists. Military officials questioned my grandmother's parents and searched their home for any evidence of Japanese loyalty, confiscating Japanese cultural objects and destroying their radio's shortwave capabilities. In Washington, my grandfather stopped leaving the house alone because he feared physical assault."

Stories of arson and assault against Japanese-Americans at the time were common, but the worst was still to come.

It Didn't Take A Lot Of Time To Go From War To Internment Camps

Things went from 0 to 100 for Japanese Americans very quickly in 1942. The Pearl Harbor attack was committed on December 7 1941, a day that, as President Roosevelt said at the time, would "live in infamy." Within a mere two months, Roosevelt had signed an executive order declaring that every Japanese American on the West Coast should be "relocated" inland, to reduce their capability for espionage.

However, this wasn't the first measure: a mere month after Pearl Harbor, in January 1942, Roosevelt had also signed a proclamation requiring every person in the U.S. who had come from an enemy country (Italy, Japan, and Germany) to register for a Certificate of Identification for Aliens of Enemy Nationality. As you can imagine, that made life a lot easier when it came to rounding up those on the list who were targeted.

Potential Spies Were Already Identified, But The Government Went All-Out Regardless

One of the many injustices of the Japanese internment is brought out by America's intelligence records at the time. Evidence pointed quite firmly to the fact that detaining everybody wasn't necessary; the Smithsonian Magazine reports that in 1942, a naval intelligence officer noted that fewer than three percent of all Japanese-American citizens would likely be interested in espionage, and that American intelligence already knew who the most likely people were and was tailing them appropriately. The internment camps, according to the most up-to-date intelligence of the time, were creations of fear based on physical difference rather than any valid suspicions of divided loyalty. It's telling that even with these warnings, of wasted assets and time, the entire program went ahead anyway.

Japanese Americans Weren't Just Interned — They Were Also Deprived Of All Assets

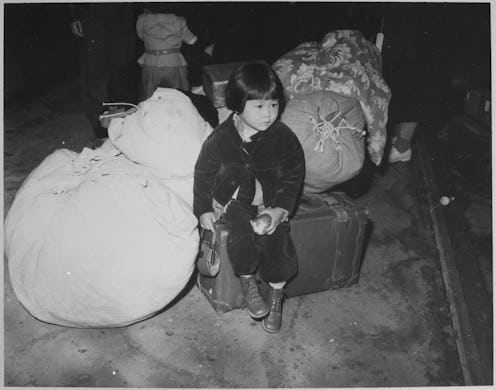

Executive Order 9066, as it was officially known, was Roosevelt's official order of internment for military command to determine whether "any or all persons may be excluded" from areas of strategic necessity (read: the entire Japanese population from the West Coast). The order was the final effort in a rapidly escalating legal war against the Japanese-American community, one of the first parts of which had been a personal assets freeze. America had already frozen all the business assets of Japan in America in July 1941, before Pearl Harbor happened, restricting its imported oil by a whopping 88 percent. Following the attack, however, the Treasury also froze the assets of every person in America who had been born in Japan, rendering them economically crippled and unable to defend themselves. When detainment started, many were gathered up with only brief handfuls of clothes or what they could carry, leaving their homes abandoned or in the care of neighbors and their businesses to fail.

In-Camp Riots & Protests Were Mostly Ignored By The Press

The internment camps themselves were dirty and unsuitable for human habitation, and inhabitants were subject to rampant abuse by guards. Later, a judge on the Ninth Circuit would call the conditions of one camp in Tule Lake "as degrading as those of a penitentiary and in important respects worse than in any federal penitentiary." However, the press was often unsympathetic to anybody's attempts to make life better within the camps, or to demonstrate their displeasure at this dehumanizing deprivation of their basic human rights. In 2014 the Chicago Tribune reflected, shame-faced, on its own position during the war: it had criticized riots as the product of leniency among camp administrators, and sneered that "no other country in the world has turned over the custody of dangerous and disloyal persons to left-wing social workers."

The Courts Failed To Protect Japanese-Americans' Rights

The courts didn't stand up for the rights of Japanese-Americans for some time. The Supreme Court came up with a bunch of contradictory rulings in 1944, after many detainees had been in camps for years, that went both ways. One, brought by Mitsuye Endo, found that Executive Order 9066 hadn't authorized internment camps at all, that loyal citizens had no legal basis to be interned, and that:

"Loyalty is a matter of the heart and mind, not of race, creed, or color. He who is loyal is by definition not a spy or a saboteur. When the power to detain is derived from the power to protect the war effort against espionage and sabotage, detention which has no relationship to that objective is unauthorized."

However, on the same date they ruled that 9066 was constitutional, and that the rights of Japanese citizens were secondary to the need to protect Americans from espionage. So a giant clusterf*ck, basically. It wasn't until 1988, when Reagan signed an act to compensate the more than 100,000 people who'd been incarcerated and offered them $20,000 each (about $40,000 today), that a modicum of justice was felt to be served. And the scars continue to run deep in Japanese communities in the modern United States.

Don't think something like this couldn't happen again. We must remain vigilant in standing up for all our civil rights.