Books

How To Write A Historical Novel, According To Someone Who Has Done It

You may only associate the term "world building" with writing science fiction or fantasy, but it is just as important when writing historical fiction. The key difference is much of the work has been done for you. Instead of spending ages building your world and establishing your rules, history holds all the answers. To write your historical novel convincingly, you simply need to unearth these answers.

What was the climate like? Size of cities? Buildings? How did people travel from point A to point B? What did they wear? Where did food and goods come from? What about social norms? What was accepted, done for fun, done for work? And on and on.

Oh wait, did I say this was easy? I’m sorry. I lied. You may not be inventing the world from the ground up, but tracking down all these answers can be tedious and time consuming. And you need to get it right! It’s historical fiction, after all. Not only will your world not be convincing if you fail, it will also be wrong.

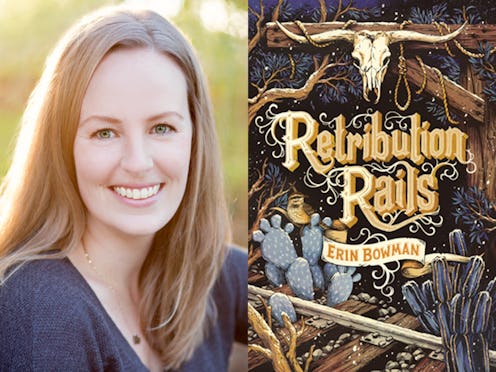

Luckily, I have some tips. While researching my western novels Vengeance Road and Retribution Rails, I relied on a variety of source material, which I've outlined for you below:

Retribution Rales by Erin Bowman, $11, Amazon

1. Books, of course

For a comprehensive history of Arizona (my setting), I turned to textbooks and bought a few nonfiction behemoths with “Arizona” and “history” in the title. I also invested in a historical atlas, which ended up being a godsend. It mapped out trails and coach routes, cities and reservations, mountains and rivers. (Many lakes in Arizona are the product of modern, man-made damming, and this atlas became one of my go-to resources for fact-checking.) Also, never underestimate the value of a simple “Writer’s Guide to ____” book. I have one for the "Wild West," which helped me nail some of my western dialect. It also provided a crash course in the era—basic definitions of farming equipment and descriptions of common wardrobe items, to name a few examples.

2. Archives

Many archive collections are now available online, and local libraries often have resources to offer in person. From photographs and journals to maps and letters, these resources are incredibly valuable because they are a true snapshot of the time. For Retribution Rails, I relied heavily on newspaper archives. On New Year's Day, 1887, my protagonists stumble into Prescott and find a gala marching up Cortez Street. The city was celebrating the completion of the Prescott & Arizona Central railroad line. Thanks to free online newspaper archives, I was able to clearly glean what that day looked like: the route the procession took through town, the band, the spectators, even the number of rifles fired in a salute at the depot. The papers I read also included quotes from public figures who gave speeches that day, and a line from one of those speeches is featured in RR! How’s that for historical accuracy?

3. Museums/Historical Societies

Looking at pictures online is one thing, but seeing a historic item in person is another. I’m very fortunate to live near Concord, New Hampshire, where the Concord coach — a stagecoach that revolutionized travel in the nineteenth century with its leather thoroughbrace suspension — was manufactured. Thanks to a local historical society, I was able to see some of these "cradles on wheels" in person. In textbooks, the Concord stagecoaches were touted as large and spacious, allowing citizens to ride in luxury. And at the time, I’m sure this was true. But seeing them in person was eye-opening. They were indeed grand in size, but the interiors still seemed tight. Bench seats didn’t look large enough to comfortably hold the number of passengers they routinely carried. I certainly wouldn’t want to ride in one for any length of time. I took note of all this, plus the fabric that upholstered the seats and the colors and designs that were painted on the carriage itself. There is nothing quite like seeing something in person.

4. Travel

Google Maps is only going to help you capture what a setting looks like, not the other sensory details. What does the air smell like? How does the sun or wind feel? Go visit your setting if you can and bring a journal to take notes. For Vengeance Road, I traveled to Arizona and explored many of the rugged areas my characters pass through. I was there in June (the same time that the book is set), while pregnant, no less. The trip gave me a new appreciation for the people who called Arizona home before air-conditioning, and I think my experiences hiking in 105-degree weather helped me effectively capture the insufferable heat during that time of the year.

That’s where the bulk of my research energies were spent with Vengeance Road and Retribution Rails. There’s of course many of other resources a writer can explore. TV and movies (much like fictional literature) can give you an idea of a place or time period—just be sure to fact-check everything. Documentaries are another great resource. If you need help understanding a specific skill, consider taking a class. (I believe YA author Stacey Lee learned how to drive a stagecoach for her western novel!) And of course, there’s always the experts. Most folks working at museums and historical societies love answering questions, so don’t be afraid to speak up.

At the end of the day, know when to stop. I could research forever. (It can be it’s own form of procrastination.) Once you’ve got a firm understanding of the world, start writing and fact-check smaller details later. Lastly, much like writing SFF, understand that while you (the author) need to know every detail about how the world works, not every detail needs to end up on the page.

I’m so sorry I ever called this easy. Turns out writing is really, really hard.