Life

I Went To A Haunted Hotel To Find Out Why Women Are So Obsessed With Seeing Ghosts

Almost half of Americans believe in ghosts, and within that group, there's another subset of people — those who not only believe in ghosts, but put time, money, and energy into actively seeking them out. These are the people who visit creepy mansions on vacation and clamor to stay in hotels supposedly haunted with restless souls. You've likely seen them on the streets of a major city, trailing a tour guide in a Victorian top hat who is pointing out various historical horrors that occurred on this very street. And, if you've been to New Orleans recently, you may have even spotted me among them.

I'm a hopeful, spiritually open woman who also happens to devour horror novels, attend ghost tours in every city I visit, and occasionally (after I've spent a bit too much time communing with the undead) sleep with the lights on. I've been this way my whole life — as a little girl, my obsession with playing "Bloody Mary" and wandering around cemeteries was matched only by my obsession with praying that no ghosts "got" me in the middle of the night.

But, I can't explain the push-pull hold ghosts had, and have, on me or my (mostly female) friends. Why have I poured so much time, money, and energy into trying to see a spirit? What the hell would I do if I actually saw one? And why does it seem like so many of the other people who feel this way are women? I decided to spend two nights in New Orleans' haunted Le Pavillon Hotel to find out.

I know I'm not alone in my urge to dedicate my leisure time to examining horrific history (instead of reading a book on a nice, ghost-free beach, like a normal person). Like a large number of tourists from the U.S. and elsewhere, I have a long-standing interest in "dark tourism" — a term that means sightseeing associated with death or disaster, and includes everything from touring the witchy Salem, Massachusetts to visiting the site of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. According to the University of Central Lancashire's Institute for Dark Tourism Research, "dark tourism" has existed in one form of another for pretty much as long as tourism itself has (see: people traveling to see medieval executions or the still-smoking battlefields at Gettysburg). Paranormal tourism — traveling specifically to spots reputed to be haunted — has been around since the Victorian era, when Americas became obsessed with connecting to the dead via seances and (mostly female) mediums. Today, most cities offer a ghost tour or two.

Interest or belief in an unseen world allows us to conceive of a universe that runs deeper than just surviving the daily grind.

But the ghost tourism in New Orleans — a place often reputed to be the most haunted city in America — leaves the spooky tour offerings of other cities in the (grave)dust. The city's tourist hub, the French Quarter, is filled with infamous and allegedly haunted properties, from a girls' school that plays a central role in American vampire mythology to a mansion that was the site of grisly, racist violence later depicted on American Horror Story: Coven. The neighborhood is also ground-zero for the city's many supernatural tourism companies, whose groups can be seen milling in the streets of the French Quarter at almost any hour during tourist season.

Richard Carradine, of Ghost Hunters of Urban Los Angeles, tells Bustle that while "visiting haunted places and hearing ghost stories is a way to confront fear of death in a safe way," people are usually interested in haunted tourism for a lighter reason: "Ghost tours and ghost guidebooks are a great way to discover the hidden history of that place. Ghost stories usually involve murders, tragedies, and lives gone wrong, which is exactly the type of things your typical tourism bureau does not want to highlight," says Carradine. "Ghost stories are sort of a peek into a place's secrets, and who doesn't like a good secret?"

On our first night in the city, my husband and I made our way to a bar a mile or two from our hotel, passing countless ghost tours filled with average-looking families. They seemed to confirm Carradine's theory – they looked like they were just having fun hearing about the gritty side of New Orleans life, not engaging a borderline-pathological need to think about life after death.

Andrea Janes estimates that about 90 percent of the people who take her company's tours are female.

But the next day, when we took a tour of the Garden District with Haunted History Tours, the situation was a little different. In our group of 10, my husband was the only man besides our tour guide. The women, all in their 40s and 50s, raucously tried to provoke a supposed ghost of a young girl, repeatedly shouting for her at various points in the tour. As our tour guide expounded on some important historical buildings, one of them loudly remarked to the other, "When are we gonna see a ghost?"

Andrea Janes, proprietor of New York City's Boroughs of the Dead ghost and crime tours, estimates that 90 percent of the people who take her company's tours are female, and she has a few ideas about why women are so eager to see a spirit.

Janes notes that the historical involvement of women in Spiritualism, as well as the idea that women are especially connected to intuition, have "branded the world of ghosts as feminine" (though she adds that she's often wondered about women's love of ghosts, and hasn't reached a totally clear conclusion herself).

But a more general explanation Janes has for the appeal of ghosts strikes me as relevant to women in particular: "Don't we sometimes wonder if there's a little more to life than 'get up, go to work, come home, Netflix, sleep, repeat?" Janes says. Interest or belief in an unseen world allows us to conceive of a universe that runs deeper than just surviving the daily grind. "Isn't that tempting," Janes asks, "to imagine there's something just a little more beyond this realm, that the world is eternal and filled with spirits?" Women — who are likely to do more household chores than men, no matter what their other obligations — get stuck with more drudgery in general. Doesn't it make sense that we'd be extra invested in believing that there was a world beyond ours — one where we'd never have to scrub a toilet bowl again?

My husband isn't some kind of skeptic who gives a side-eye to my undead fixation; he's the one who's actually seen a ghost.

Amanda Lipman, sales manager at the haunted Le Pavillon hotel, agrees that female customers as the ones most interested in the building's eerie history. And this doesn't just apply people who come specifically for ghost-hunting trips — she tells me that she's met with numerous brides who were looking for a bridal suite in the hotel, but got sidetracked asking which rooms were haunted. Male customers, meanwhile, "usually drop out of the conversation once the women bring it up."

Jessica Shashaty, a publicist who works with Le Pavillon, theorizes that perhaps this is because "women are acutely interested in the intricate history and great tragedy surrounding it all. Men usually only find the actual 'scare' thrilling."

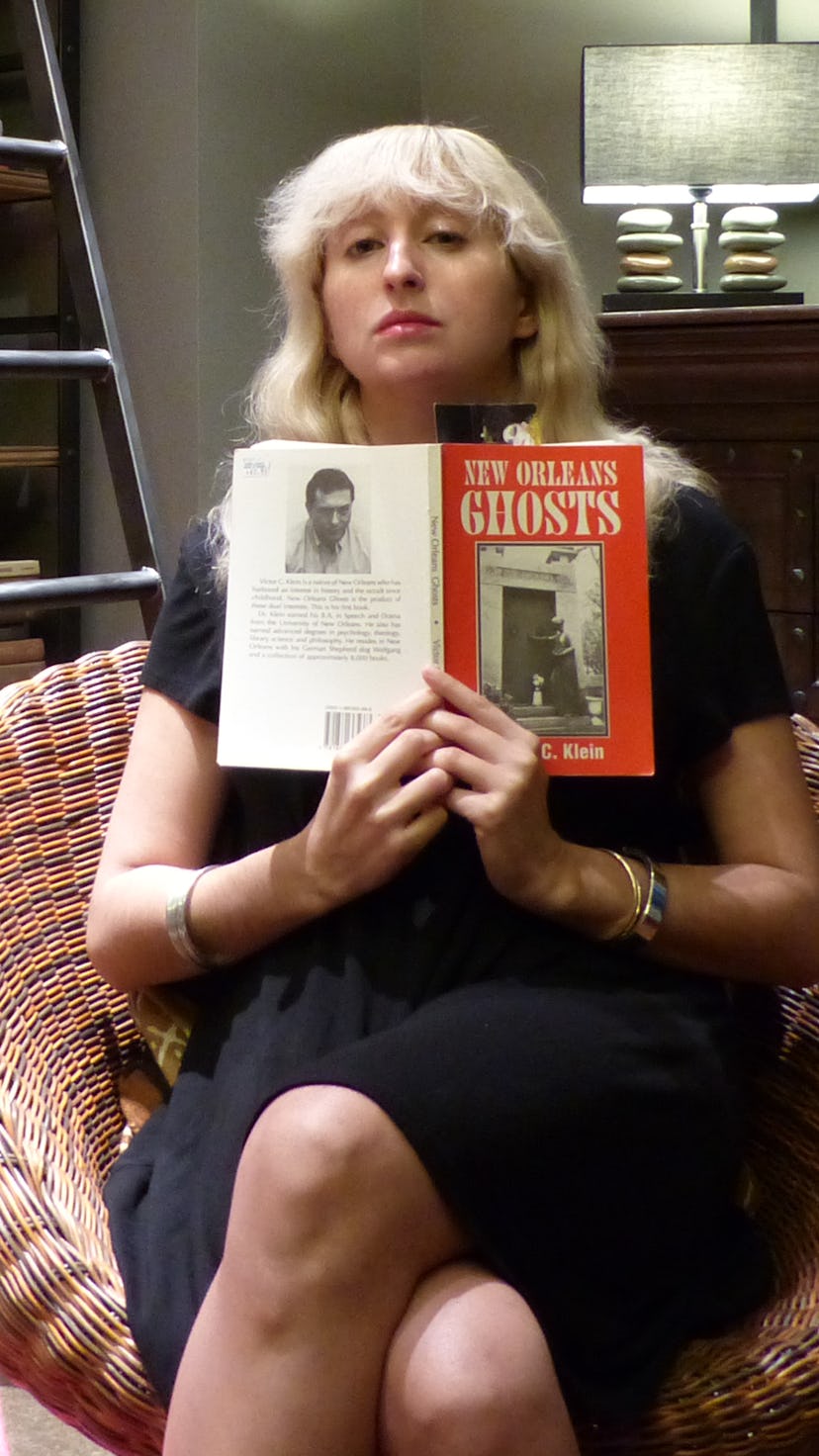

I knew this was true in my relationship, where my husband indulges my ghost obsession without necessarily understanding it himself (he also took that picture above of me using my "ghost radar" app next to that spooky-looking painting). He was happy to take a trip to New Orleans and stay in a gorgeous, historic hotel — but he was not anywhere near as excited as I was when we read a historical pamphlet describing how Le Pavillon was built on the site of a theater that had mysteriously burned down in the late 1800s. I started shouting, "This place has gotta be haunted as hell!" He smiled, but more because he enjoyed my enthusiasm than anything else.

The thing is, my husband isn't some kind of skeptic who gives a side-eye to my undead fixation; he's the one who's actually seen a ghost (for the record: I was there, and I had no idea what the hell was going on). But he doesn't really care about ghosts, or true crime, or any of the dark fixations that I and so many of my female friends have. The idea of an eerie, unseen world just beyond our own doesn't shape his life in the same way it shapes mine.

When I look for a haunted sight to visit, I look for the best story.

Lots of theorists posit that women love true crime because it helps us feel like we're learning things that will help us not become victims, or allows us to deal with repressed aggression in a way that feels safe. But one explanation that always resonated with me, and that could apply to ghosts, too, is that it keeps the stories of forgotten people alive.

As in true crime, there is a complicated dance of privilege at work in ghost tourism — many criticisms of ghost tours hold that they are classist and objectify the lives of their subjects (often marginalized people like slaves, sex workers, the mentally ill, or immigrants, whose deaths were often directly tied to their marginalization). There is, obviously, privilege inherent in spending time and money just to feel scared, and some ghost tours — like those offered at Southern plantation sites — are as cruel and tasteless as a "ghost" tour of Auschwitz. And if New Orleans is actually the most haunted city in America, that title would have to be connected to the fact that the city played a role in the slave trade, was a site of Civil War violence, and has otherwise hosted the kind of pain and suffering that is so strong, it could last beyond death.

But for me, there's always been something about the way ghost legends can help people remember others across the centuries — often women (many of America's most famous ghosts are supposedly female) whose lives were cut short by brutal people or an unfair world. I'm not saying I deserve a Nobel Peace Prize for hanging around a creepy mansion. But when I look for a haunted sight to visit, I look for the best story — and for me, those stories are often ones about women unfairly cut down in their prime. I take some peace in imagining that being the victim of someone else's violence wasn't the absolute end for them. Maybe that's what religious people feel when they contemplate the afterlife: a sense that there's more to existence than just pain and chaos, even though you have no real concrete proof. They believe in God. I believe in ghosts. Either way, it helps us get out of bed in the morning.

Now, about those actual ghosts: though many hotels allow ghost tours on their grounds or benefit from the publicity of being included in "haunted hotel" articles, Le Pavillon was the only hotel willing to actually go on record about being haunted with me, and for that, I was appreciative. Le Pavillon stands by their ghosts, which is probably why they're reputed to have so many. But while I read a detailed dossier on the spirits that supposedly call the hotel home (a 1920s couple in their going-out clothes! A boy who loves pranks!), I did not encounter any apparitions, floating photo orbs, or any phenomena that was in any capacity unexplained. I didn't have to confront what it would mean for my ghost fixation, or all my philosophical justifications for it, if I actually saw one. I just spent a pleasant weekend in a very nice hotel, eating room service peanut butter sandwiches, without any having supernatural visitors at all.

Or maybe I did. After all, isn't that the great things about ghosts? I'll never really know.