News

Seeking Asylum In The U.S. May Have Saved My Life

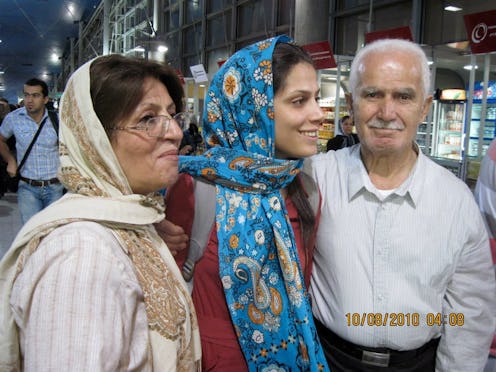

I left Iran for American University on August 10, 2010. Though I was 24 years old, I had never left my home country before. American U. had given me a full scholarship to obtain a second law degree, so I accepted the invite and came to the states on an F1 student visa. Because of U.S./Iran sanctions already in effect at the time, I arrived in Washington DC without so much as a credit card or cellphone to my name. My father, having been well aware of these sanctions beforehand, had stuffed $10,000 in my pocket before I’d boarded my flight and said, “Good luck, daughter.” He'd sold a piece of land to give me that money.

When I landed at Dulles International Airport, I had no idea what to expect — no clue what the weather might be like; no clue where I was, geographically, inside the U.S.; no clue where I could go for assistance. I had 10 days to settle into America before my first semester at American University started. My ex-boyfriend’s brother, who lived in North Carolina, did me a favor and booked me a room at a nearby motel, in what I later learned was a high-crime neighborhood in Takoma Park, Maryland.

It was there that I set about looking for a bank and a cellphone, traipsing about, asking strangers for help — “Vhere eez bank?” — with the visible $10,000 wad of cash in my pocket. A West African lady caught me and asked if I had a death wish. I told her I did not; I just wanted a bank account. She assisted me in the process of opening one up and securing a cheap cellphone.

I had to forgo the familiar forever — and for a place in which I often felt, and still feel, unwelcome. I had no other choice.

Once I'd started school, I went through a string of bad experiences with odd roommates and shoddy landlords with whom I opted to live in order to keep my expenses cheap. Regardless, I managed to achieve "Master of Law" status round two in August 2011. That same year, I began working as a legal researcher for a human rights NGO that curated cases involving Iran’s various human rights violations dating back to the revolution in 1979. My job was to identify victims, interview them, document their stories, and, every once in a while, draft an urgent appeal to bring before the United Nations.

This job landed me on the Iranian government’s “watch list,” specifically with its Ministry of Intelligence. I knew that this position could pose such a problem before I began, but I have a set of personal values by which I've always stood — and escaping perceived threats is not one of them. If everybody hides from danger, who changes the world? I started receiving emails cautioning me about my immediate arrest should I return to Tehran one day. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Iranian Intelligence, and later the Iranian Parliament, issued separate communiques claiming that employees of such agencies (my employer, of course, was on their list) were actively “waging war on God” and “committing crimes against Iranian national security.” My life was now in danger, particularly if I returned home. So I decided to seek asylum status in the U.S.

Seeking asylum in the U.S. was not a pleasant experience. I don’t understand why people so often think that asylum-seekers come here to America, love it, and just decide they want to stay. That’s almost never the case. In fact, it’s an extremely painful decision to make. I knew that seeking asylum meant I would never see my favorite stray cat again, that I would never again pass by that annoying old man who had a store at the end of the street on which I grew up. Unlike back home, I didn’t even have a favorite cartoon to share with my friends here. That small fact, amid so many others, made me feel isolated beyond words. I had to forgo the familiar forever — and for a place in which I often felt, and still feel, unwelcome. I had no other choice.

I also couldn’t tell my family I was seeking asylum at the time. In Iran, there is decades-worth of propaganda that denigrates Iranians seeking asylum and refuge in other countries as “traitors” who “don’t care about their own country.”

I’d first heard the unfavorable Farsi term for “refugee” — Panahandeh — when I was four. A man walked into my father’s office one day. This man didn’t just look old to my four-year-old self — he looked broken, like a “walking sadness.” He spoke to my father a while and, once he left, I asked why he was so sad. My father said, “He has four children — two who were executed, one who is in prison, and the fourth,” my father said, disparagingly, “is… Panahandeh.”

I was afraid I would hurt my parents’ feelings if I admitted that I was seeking asylum in America, and I also feared I’d bring danger upon them. So I never told them the truth.

My father passed away this past December without ever knowing, thinking I would come back one day. What tortures me the most is a conversation we had shortly before his death. He told me over the phone that he wanted me to sit with him on his balcony to watch the Caspian Sea. "When the U.S.-Iran relationship finally gets friendly,” he said, "then you should come home and stay with us here for a bit. The view is great!”

He was in a wheelchair by that time, and couldn't leave the house. All he had to offer me was just this view from where he sat. Later on, before his death, he lost his ability to speak and to recognize people, which meant I lost the chance to even hear his voice on the phone. I may never look at the Caspian Sea ever again.

I have been told numerous times by people who don’t know my story that I have no right to be critical of America's immigration policies. To these people, I just laugh — mostly because I know these folks are descendants of immigrants themselves, but are just too far removed from their ancestors’ passage to realize it. Their willful ignorance gives me even more determination as a soon-to-be lawyer to help the people who would give anything — have already given everything — to be here.

Nobody leaves the safety of home to go to an unknown world where she will almost certainly feel unwelcome — especially in America right now. They do it because they honestly have no other choice.

As told to Abby Higgs.