Wellness

How I’m Managing My Risk Of Ovarian Cancer After Dealing With My BRCA 2 Diagnosis

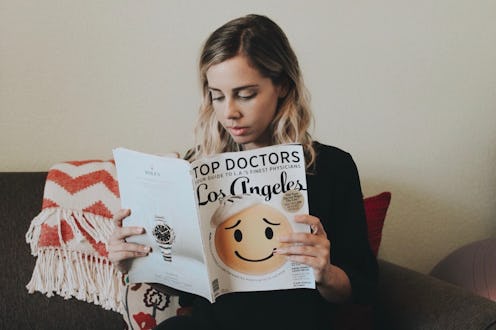

In Bustle's Braving BRCA column, writer Sara Altschule opens up about how she is managing her risk of ovarian cancer and her emotions at the same time.

When I first found out I carry the BRCA 2 mutation, which means my cancer suppressing genes don't work the way they should, I was mainly focused on what that meant in terms of my increased risk for breast cancer. I didn't really stop to think much of my ovarian cancer risk that comes along with this diagnosis. But after I conquered my double mastectomy and reconstruction, which brought down my lifetime risk of breast cancer to less than five percent, I realized that I had another body part to attend to — my ovaries.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center says that, for BRCA 1 carriers, the risk of ovarian cancer is between 40 to 60 percent by the age of 85. And for BRCA 2 carriers, like myself, the risk is between 16 and 27 percent. To give you some perspective, in the general population, a person with ovaries has a 1.3 percent risk of developing ovarian cancer according to the National Cancer Institute. So, as you can imagine, I want to do whatever I can to properly manage my ovarian cancer risk. For me, this means screening every six months — a CA-125 blood test (very easy), a pelvic exam and a transvaginal ultrasound (as awkward as you'd think).

It's a weird feeling knowing that I have an increased risk of developing this disease. I am living my 'normal' life, going to work, hanging out with friends and dating, but then sometimes I remember I'm a part of this BRCA club. After my preventative double mastectomy in September, part of me wanted to just move on. I had experienced such a monumental surgery, and after, I wanted to feel normal again. I didn't want to have to think about this diagnosis anymore — I wanted to mute my mutation. But I still have my ovaries to think about.

I'm not going to sugarcoat it: Ovarian cancer sounds terrifying. My dad's cousin, who was the first person in my family I knew of who had the BRCA mutation, sadly passed away from ovarian cancer in 2011. And even though my risk for ovarian cancer is lower than my risk for breast cancer, I would be lying if I said I wasn't scared.

The most alarming part for me is that most women don't find out they have ovarian cancer until it's already at an advanced stage (stage III-IV), where only 30 percent of patients survive more than five years after diagnosis. Only around 20 percent of women find out they have ovarian cancer at a point where it's treatable. Unfortunately, the screening they have available today to detect it early isn't that great. Sometimes, these tests won't detect it early enough, and other times these markers show false positives, according to the FDA. But, it's the best way of testing for ovarian cancer at the moment, so I'll take whatever I can get.

I felt a sense of gratitude that I have this prior knowledge of my increased risk of cancer, and I can manage it an informed way. And I also felt dread that this is going to be my life every six months.

For BRCA 2 carriers, the national recommendation is to undergo an oophorectomy (removal of ovaries) and a salpingectomy (removal of fallopian tubes) between the ages of 40 to 45, according to the National Cancer Center Network. For BRCA 1 carriers, the recommendation is to have your ovaries and fallopian tubes removed between the ages of 35 to 40.

I thought I had put everything behind me until I had to an appointment with a gynecological oncologist at a cancer center in Los Angeles. That's when it all hit me again. The moment I walked in and saw the other patients around me, all of my emotions came back. Right away, I wanted to cry for so many reasons. I felt a sense of gratitude that I have this prior knowledge of my increased risk of cancer, and I can manage it an informed way. I felt a sadness for the people around me who aren't so lucky. And I also felt dread that this is going to be my life every six months. There is no forgetting about my mutation.

The oncologist reassured me that my risk of ovarian cancer is actually decreased because I've been taking oral contraceptives for a greater portion of my life. (Thanks, Mom, for putting me on the pill when I was younger.) He also just put my mind at ease when it comes to how likely it would be that they found something alarming when I have to do my testing (around a 5 to 10 percent chance). Of course, like the anxious over-thinker I am, I asked him about what surgery would be like when I decide to remove my ovaries and fallopian tubes 10 to 15 years from now. The doctor told me if I could have a prophylactic double mastectomy, I can definitely do this.

Still, there is a lot to be nervous about when it comes to these surgeries. For instance, removing your ovaries puts you immediately into menopause, which has its own separate set of issues, according to the Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research. Some of these can include bone loss, lower libido, hot flashes, vaginal dryness and/or night sweats. Even if it would lower my risk of ovarian cancer to zero, I'm not so sure this is a fair trade-off for not having any more periods. Isn't there a better compromise?

After my visit to the doctor, I was reminded of how happy I am that my double mastectomy is behind me. Going to the cancer center and having these conversations definitely heightened my anxiety, but being able to have a sigh of relief that my biggest hurdle — my mastectomy — is over with, I felt good. And most importantly, I felt strong.

Even though having to manage my cancer risk can get me a little down sometimes, it's important for me to remember that knowledge is power. The fact that I am able to know I have this high risk is a blessing. I'm able to take precautions and measures to increase my chances of living a longer and healthier life. Maybe it's OK to not be "normal," and to realize that having a mutation makes me unique. This mutation has made me stronger. In fact, I like to think of it as my very own super power.

This article was originally published on