Books

How 'Pride & Prejudice' Gives Authors A Foundation To Write About Diverse Experiences

Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice is a story that’s been told, and retold, over and over again. The plot is a classic: girl meets boy, boy meets girl, strong personalities reveal themselves as opposites attract and reject (and attract and reject) until finally all parties are paired off to the concluding satisfaction of them and the reader. Reflected in each meet cute, romantic stumble, and wild-haired tear through the fields of Hertfordshire are larger, more complex statements about restrictive gender roles and oppressive social structures, and the fortitude of spirit it takes to overcome the cultural and financial limitations of one’s time. (Seriously, don’t let Colin Firth and Matthew Macfadyen getting all drippy distract you from what’s really at play here.)

In other words, it’s a truth universally acknowledged that readers, regardless of their fortune, will never tire of Pride and Prejudice retellings. Or at least, I won't. And writers, it seems, will never get sick of writing them.

But why? What is it about Austen’s specific story and particular characters that makes Pride and Prejudice so irresistible — and so adaptable? Because there aren’t just a few Pride and Prejudice retellings out there. There are hundreds of them.

If you’re a bit of a Janite (a.k.a.: Jane Austen superfan) you’re probably already well-versed in the Jane Austen retellings that transport Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy across time — from Lizzy’s early 19th century Meryton to Bridget Jones’s late 20th century London. Austen’s themes — love, desire, peer pressure, familial expectations, financial restrictions — translate well across time. They’re recognizable; they’re relatable; they’re universal.

But these ideas: the irrepressible attraction of opposites, how be in a relationship without sacrificing your autonomy, how to follow your instincts without disappointing your family, how to establish fiscal independence in a world where women are (still) paid less than men, how to navigate social hierarchies, also translate across culture.

Austen’s themes — love, desire, peer pressure, familial expectations, financial restrictions — translate well across time. They’re recognizable; they’re relatable; they’re universal.

In YA author Ibi Zoboi’s Pride, for example, Zuri Benitez is a Haitian-Dominican teen from a working-class family living in Brooklyn, pitted against the wealthy Darius Darcy, whose family has come to "clean up" their neighborhood. But whereas Austen’s original Fitzwilliam Darcy provided an opportunity (however gendered) for Elizabeth Bennet to transcend her 19th century economic class, Zoboi’s characters force readers to grapple with the increasingly complex issues of modern income inequality and gentrification.

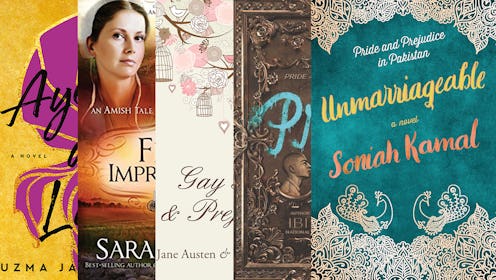

Uzma Jalaluddin’s debut novel, Ayesha at Last, retells Pride and Prejudice in a closely-knit Muslim community in Toronto, where a progressive 27-year-old woman named Ayesha Shamsi is lonely, in debt, and doesn’t want an arranged marriage, but is struggling with her feelings for the traditionally conservative Khalid Mirza. But while the romantic underpinnings might mirror those of the original novel, the Islamophobia that both characters face, and their disconnect over Islamic fundamentalism, definitely adds a new layer to Jane Austen's foundation.

"...Fitzwilliam Darcy provided an opportunity (however gendered) for Elizabeth Bennet to transcend her 19th century economic class, [but] Zoboi’s characters force readers to grapple with the increasingly complex issues of modern income inequality and gentrification."

In Soniah Kamal’s Unmarriageable, (publicized as Pride and Prejudice set in modern Pakistan,) Alysba Binat’s ideas about education and independence could be the only things influencing her all-female high school students to stay in school, rather than commit to arranged marriages while still in their teens. In Sarah Price’s First Impressions, Austen’s plot is recreated in a contemporary Amish setting, in rural Pennsylvania, highlighting how the same antiquated pressures surrounding morality, education, and manners still reverberate through some American subcultures today. Kate Christie’s Gay Pride and Prejudice is exactly what it says it is.

Jane Austen's work is adaptable and resilient. Pride and Prejudice retellings highlight the experiences of women from a diversity of racial and ethnic backgrounds, living in countries and cultures around the world, but built upon stories that are known and beloved by so many readers. These authors highlight how the same experiences of Jane Austen's books — marriage, poverty, education — can take on a different gravity, depending on where a person comes from. Jane Austen retellings remind readers the world over of all our similarities, while also giving voice to all our differences.