Books

Sabina Khan Wrote Her Novel So She — And Her Daughter — Could See Themselves In A Book

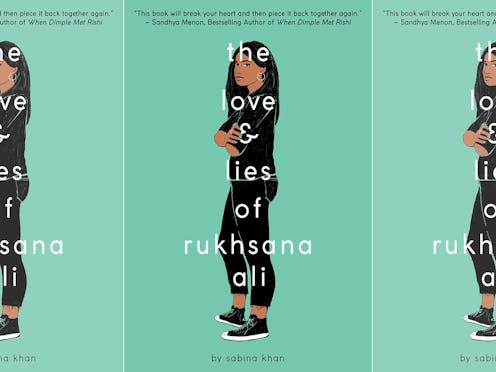

While author Sabina Khan recovered from a burst appendix as a child, her older sister gave her The Phantom comic books to pass the time, and her friends dropped off copies of Enid Blyton’s boarding school series. She devoured them all — and, from then on, she considered herself a voracious reader. It was books that eased the transition when she moved from Germany (where she spoke Urdu at home and German at school), to Bangladesh (where everyone spoke Bengali and English) at just eight-years-old. Yet, it didn't occur to her until decades later that books could feature protagonists that looked like her, because all the stories she read centered on white characters. In the last several years, the movement to diversify children's literature has intensified, and Khan began to see characters of different backgrounds represented in books. She decided to write a novel with a character of her cultural background — and The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali is the result.

“In my wildest dreams, I never imagined this,” she tells Bustle. “Even five years ago, you would be hard-pressed to find any titles like this.”

The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali tells the story of closeted lesbian Rukhsana Ali, who feels like she is being pulled in opposite directions by the people she loves most: Her parents, who want her to uphold their Bengali culture in Seattle, and her girlfriend, who wants her to be transparent with her family about their relationship. Rukhsana fears these equal parts of her identity cannot blend together harmoniously.

Khan says that teen readers who acquired advanced copies of the book have sent her private messages, saying they felt seen for the first time in a book. "This is good for so many people who felt invisible, like their stories don’t matter," she says. "People really want to hear our stories now.”

As someone who grew up bullied for being brown and Muslim in small-town Germany, it’s a “total shock” that her coming-of-age story about a LGBTQ Bengali-American was named one of the most anticipated releases of 2019.

Growing up in Germany, she was the victim of taunts like “Your skin is brown because you’re dirty!” that made her afraid to go outside at recess. When she was in the third grade, her family relocated to Bangladesh, and her extended family surrounded her like a warm embrace.

Within six months of arriving in Bangladesh, Khan taught herself to speak Bengali and English fluently, and by the end of elementary school, she says she had read every book in the school library. Khan graduated from reading Enid Blyton’s mystery series to devouring adult books by Sidney Sheldon. Without a selection of young adult novels to smooth her transition to more mature themes, Khan was introduced early to a fictional world of sex, drugs, murder, and violence, though a lot of it went over her head. Years later, Khan began reading YA books alongside her oldest daughter so they could discuss them together. “It was so refreshing to read these voices!” she says.

When she discovered YA literature, Khan was several years away from beginning her own writing career. She was instead focused on her own building her tutoring company, where she taught math, chemistry, biology, and English. When the family relocated from Corpus Christi, Texas to Vancouver, Canada, she brought the business with her.

Khan is thankful her family settled in a diverse community, because when her youngest daughter turned 17, she came out as bisexual. Khan says she was proud that her shy daughter felt confident and safe enough to share her sexuality with her parents, because she knew she would receive unconditional love and support. This was a far cry from Khan’s own parents’ reaction to her marrying a Hindu man. Khan and her husband married against both their families’ wishes and were ostracized during their early years as a young interfaith family.

After Khan’s daughter came out, the two of them began looking for books with Muslim LGBTQ characters that they could read together, but they couldn’t find too many titles beyond Tell Me How a Crush Should Feel by Sara Farizan. The fledgling idea of writing her own book started to take shape, but Khan didn’t think she had the time, or the ability, to write it.

Trying to find relatable YA books for her daughter would not be the first time Khan encountered a lack of representation in literature. Khan says that until she was a young mother, “all the stories I read were white. I didn’t relate to their experiences, but it didn’t occur to me to question it.” When she and her husband — who grew up in India — first moved to Corpus Christi, they lived four hours away from the nearest Indian restaurant and were surrounded by few other South Asians. But then a local librarian made several recommendations to Khan that changed her life. Through the writings of Indian-American authors like Rohinton Mistry and Chitra Benerjee Divakaruni, Khan got a taste of her heritage in a way she had never experienced before. Not only did they write about the immigrant experience — they won literary awards for writing about it.

Fast forward to April of 2016, when Khan wrote the first draft of The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali in 16 feverish days. When she heard news of the brutal murders of LGBTQ organizers and bloggers who worked for Roopbaan and Boys of Bangladesh, she felt compelled to write about that piercing betrayal by her home city and country. While Bangladesh had been a welcome reprieve for Khan after the prejudice she experienced in Germany, now the hypothetical prospect of her daughter visiting Bangladesh terrifies her. “I can’t protect her from it, and it enrages me that’s the case,” she says. “There must be so many Muslim LGBTQ teens struggling. It’s horrendous.” Khan was struck with a burst of inspiration to write a first generation Bengali North American character who has a very different coming out experience than Khan’s daughter.

Yet Rukhsana, like Khan, is defensive about her identity and her culture in a way that her white friends don’t have to be. Prejudice and intolerance are certainly not specific to Bangladesh or Islam, yet Rukhsana’s friends insinuate that her parents’ strictness is due to being immigrants from an "oppressive" culture. “When a white teen white can’t go to a party, no one says their entire culture is to blame,” Khan says. “It’s just your weird parents. One family. One story.” Although the main conflict of The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali does stem from Rukhsana’s parents not understanding her homosexuality, Khan portrays them as nuanced characters who — in their own warped, uniformed way — think they’re protecting their daughter. “It’s hard to unlearn what you’ve been taught all your life,” Khan says.

Though Khan does not shy away from the bleak realities that LGBTQ Muslims might face, readers will be heartened to know that The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali does have a happy ending. Khan is determined to write books for kids who feel trapped in their situations. "Where do you turn as a teenager, when you’re dependent on your family, financially and emotionally?" she says. "They can’t even turn to books because there aren’t enough books." Books like this help validate readers’ experiences, and hopefully, they will alleviate some of the prejudice born from ignorance.