Books

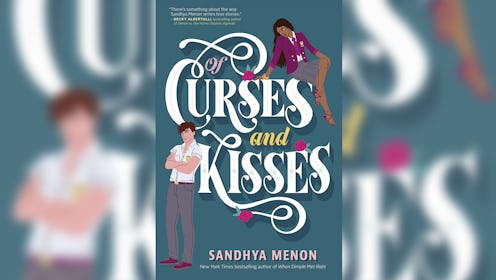

Start Reading From This "Beauty & The Beast" Retelling Set At An Elite Boarding School

Amazing news for fans of dreamy young adult romances: When Dimple Met Rishi author Sandhya Menon is releasing a new YA series, and the first book is a contemporary spin on "Beauty and the Beast" set at an international boarding school, with a feisty and conniving heroine at its heart. The first book in Menon's new St. Rosetta's Academy series, Of Curses and Kisses, is out in February, but you can get an exclusive sneak peek at the cover and the novel's opening chapters right now! Keep reading to find out more about Sandhya Menon's Of Curses and Kisses, and get ready to pick up your copy of the book when it lands in stores on Feb. 18, 2020.

Sandhya Menon skyrocketed to the forefront of YA romance after When Dimple Met Rishi arrived in stores in 2017. Menon went on to publish two more YA rom-coms — From Twinkle With Love in 2018 and There's Something About Sweetie in 2019.

Of Curses and Kisses follows Jaya Rao, a princess of the Imperial House of Mysuru, as she goes off to spend a year at St. Rosetta's Academy in Colorado. The move is all part of Jaya's big plan to avenge her younger sister, who has become the latest target of an age-old family feud between the Raos and the Emersons. Jaya intends to make Grey Emerson, a St. Rosetta's student, fall madly in love with her before she breaks his heart. What she doesn't account for, however, is the chance that she might actually fall for Grey instead.

Sandhya Menon's Of Curses and Kisses is out Feb. 18, 2020 and is available for pre-order today. Start reading below!

Of Curses and Kisses, $18, Amazon

Chapter One

Just outside Aspen, Colorado, nestled between the sentinel mountains and an inkblot lake, lies St. Rosetta’s International Academy. Its sweeping spires, creeping ivy, and timeworn brick turrets often lead visitors to remark that it looks like a venerable castle from an old European city. The Academy would be Princess Jaya Rao’s home for the next year.

While she was there, Jaya had one mission: break an English nobleman’s heart.

But first she had to fall in love with him.

Chapter Two

Jaya

Being a princess wasn’t as glamorous as the media might have you believe. If the courtiers introduced her, say, in this fashion: “Her Royal Highness, Princess Jaya Rao of the Imperial House of Mysuru,” most people would immediately picture Jaya cooing to birds and shaking hands with friendly mice, tiara glimmering in the summer sun. The entire Disney enterprise had a lot to answer for, in her opinion.

Jaya’s reality was actually quite different. It was always, “Jaya, the townspeople want you to feed their lucky elephant so it’ll win in the races tomorrow. Oh, and by the way, the elephant is in mush, so watch your dress” or “Jaya, the Prime Minister of Oppenheim is morally opposed to butter, so you cannot have any at breakfast either.”

But it was all right. She was the heiress to the “throne” of Mysuru. (Technically, India was a democracy now, not a monarchy, but Jaya’s family used to be the monarchy in this region and still carried the title.) Jaya understood that she would, at some point, have to grasp the reins. She’d have to take care of the city she lived in, just as her father had for years and her grandfather did before him. India wasn’t supposed to have royal families — except the open secret was that they were still there, and people still looked to them to be benevolent, firm, and fair. Non-royals depended on them for jobs, for charity, and for a million other reasons Jaya was still learning. Maybe because of this, the Raos were placed upon a pedestal. They were, fairly or unfairly, expected to be perfect in every way; the common citizens needed them to be. The Raos’ family name and the royal traditions that bound them were everything.

And that was precisely why she had to do what she was about to do. She might be a princess, her parents’ firstborn child and the heiress ascendant to the throne, but that wasn’t all of her story.

They stood in the grand marble entrance with their small bags. Jaya tipped her head back to look at the enormous crystal chandelier suspended like a dewdrop above her head. The rose pendant hung heavy from her neck, eighteen rubies glinting like watchful eyes, reminding her why she was there.

She might be a princess, her parents’ firstborn child and the heiress ascendant to the throne, but that wasn’t all of her story.

Isha whistled, low and long, and Jaya glared at her. She cut off mid-whistle, looking only slightly abashed. “Nice setup,” she whispered, but her words echoed anyway. “Nicer than our last boarding school in Benenden, even. And the English really know boarding schools.”

The wall before them was adorned with flags of more than three dozen countries. A gold-plated sign above them boasted, “Our students come from around the world!” Jaya’s gaze was drawn automatically toward the flags she knew very well — India, of course, along with the US, UK, UAE, China, Japan, Mauritius, and Switzerland. She’d spent summer holidays in all these places and lived in most of them, reading in cafés and parks while Isha foraged through thrift stores, searching for gears or batteries for whatever contraption she was working on.

The floor was drenched in sea-green tiles inlaid with gold, a splash of oceanic beauty here in the mountains. Jaya had heard it rumored that these were a gift from the Moroccan king half a century ago, when his son had been exiled here after an embarrassment of some kind. She hadn’t ever unearthed what that scandal was — St. Rosetta’s was very good at burying what they didn’t want found — though she felt a kinship with the king. He wasn’t the only one who’d shouldered the responsibility of protecting a wayward family member. Jaya’s eyes fluttered to Isha unwittingly, and she forced them away.

Isha gripped her arm, pointing to the wall on their right. “Look!” she whispered. “Is that... ?”

They ogled a cluster of colorful paintings, large and small, that contrasted with the Moroccan tiles, depicting smooth desert landscapes that lifted off the page and caressed the eye. “I think so,” Jaya whispered back, thrilled. She wasn’t sure exactly why they were whispering. Maybe because they were in the presence of greatness? It was probably why people felt compelled to whisper in libraries, too. “Georgia O’Keeffe spent a semester here as a teen, and later donated paintings to the school as a thank-you.”

She hadn’t ever unearthed what that scandal was — St. Rosetta’s was very good at burying what they didn’t want found...

Before Isha could respond, thunderous footfalls came rushing down the opulent marble stairs that faced away from them. Without even turning to look, Jaya could guess from the boisterous, deep laughter that it was a couple of boys, though the sheer amount of noise could also indicate a herd of buffalo.

“Come on,” her sister said, tugging her forward.

Jaya grasped her wrist and shook her head. “Isha.”

“What?” Isha said, her brown eyes wide. “I just want to get to know our schoolmates. We have to spend the next year or two here with them anyway.”

As if Jaya trusted those innocent doe eyes. Isha thought she was much more naive than she really was. Lowering her voice, Jaya said, “And boys have gotten you in trouble in the past.”

“That is so typical,” Isha hissed. “You treat me like such a baby sometimes. It wasn’t boys that got me in trouble. It was the stupid rules.”

Jaya opened her mouth to respond — something scathing about the virtues of rules; she hadn’t worked out the details yet — but a jovial voice interrupted.

“Bonjour! Are you beautiful ladies new?”

Jaya turned toward the rich French-accented voice. Two boys had rounded the corner and now stood before them. The tall, broad one who had just spoken smiled warmly, like he was greeting old friends. His skin was a golden brown and his straight dark hair hung to his shoulders. Jaya was fairly good at guessing ethnicities, and she thought he was likely a blend of Southeast Asian and Western European.

Isha set her bag down and stepped forward before Jaya could stop her, proffering a hand. “Isha Rao. This is my sister, Jaya. I’m a sophomore, and she’s a senior.” They shook, and Jaya managed not to wince at Isha’s firm handshake, a reminder of her sister’s... indomitable spirit.

Jaya pushed her annoyance away. It wasn’t entirely Isha’s fault. No one would’ve known what Isha was up to if the loathsome Emersons hadn’t set her up. Why blame Isha for the Emersons being a bunch of grunting troglodytes wrapped in aristocratic finery? Just thinking of it made Jaya want to strike something. (Not that she ever would. That wouldn’t be behavior befitting the heiress to the Rao dynasty.)

The Emersons and Raos had been at it for a long time. In fact, Jaya and Isha’s father, or Appa as they called him, said he couldn’t remember a time when the clans weren’t fighting. In the mid-1800s, during the British colonization of India, the Emerson family had infamously stolen a beloved and sacred ruby from one of Mysuru’s temples. Even after India had achieved independence, the Emersons refused to return the ruby, claiming it had belonged to them all along.

But Jaya’s great-great-grandmother got the last laugh. She cursed the ruby, something about it bringing misfortune to the Emersons and eventually resulting in a termination of the bloodline. She also made sure to circulate the news about the curse far and wide — far enough and wide enough to reach the Emersons. To make them sweat and rue the day they’d cheated the Raos, ostensibly.

Obviously, Jaya didn’t believe in the legitimacy of the curse. She was a child of the twenty-first century. Still, her great-great-grandmother’s generation had believed in it, and for many years, Jaya hadn’t understood why her relative would curse an entire lineage to end. Yes, they’d stolen a ruby, but that had been in the 1800s. Why, in the mid-twentieth century, would her great-great-grandmother have done something so cruel?

Then Appa had explained to Jaya how much pain and suffering there had been during the British Raj. By stealing the ruby and then refusing to return it, the Emersons hadn’t just taken a jewel. They’d seized a piece of vital Indian history they had no claim to. Then, even when the British finally gave India back to her people, the Emersons had kept the ruby as a token of their superiority, of their arrogance, of their ultimate victory. It was this final insult that Jaya’s great-great-grandmother had been unable to abide. Remorselessness was absolutely cause for execration.

Obviously, Jaya didn’t believe in the legitimacy of the curse. She was a child of the twenty-first century.

Now Jaya finally understood her great-great-grandmother’s rage. It was nearly impossible to look the other way when someone hurt something you cared for so deeply and refused to atone.

She set her bag down like Isha had and forced herself to smile. “How do you do? We’re new this year.”