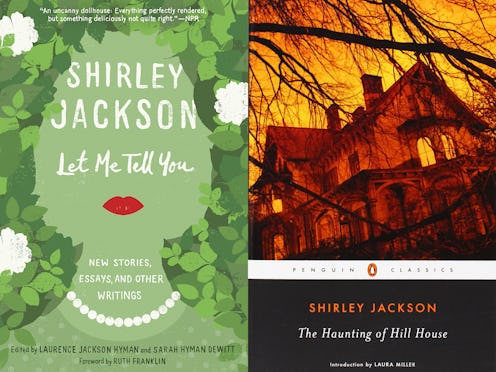

If you are at all familiar with the life of author Shirley Jackson, then you already know that her affinity for the supernatural went far beyond her work. Best known for her macabre fable "The Lottery," one of the most famous short stories in American history, and her classic of the haunted house genre, The Haunting of Hill House, Jackson was a lifelong aficionado of all things magical, and it profoundly impacted her writing.

"Jackson had always had an imaginative, even magical mind, filled with witchcraft lore, myths, and fantasies of her own devising," her biographer, Ruth Franklin, explains in Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, excerpted by The Cut. Jackson, who had four children with her husband, literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, was a daydreamer by personality, to be sure, but her affinity for the fantastical also helped her maintain her prolific writing while raising a family with little help from her husband. (Jackson's complicated feelings about her role as a housewife are discussed in depth in Franklin's biography.)

In Let Me Tell You, a collection of Jackson's previously unpublished short stories and lectures on writing, she discusses her quirky writing techniques, many of which take place away from the typewriter. In "How I Write" — one of the five essays on writing included in the collection — the author speaks of her ability to create stories no matter what she is doing: vacuuming, cleaning, letting the dogs in and out of the house, etc.

She writes:

"Most of my time, actually, is spent doing things that require no very great imaginative ability, and the only way to make these mechanical jobs more palatable is to think about something else while I am doing them. I tell myself stories all day long, and have managed to weave a fairy tale of infinite complexity around the inanimate objects in my house, so much so that no one in my family is surprised to find me putting the waffle iron away on a different shelf because in my story it has quarreled with the toaster, and if I left them together they might come to blows; they had quarreled, incidentally, over my getting some of the frozen waffles you drop in the toaster, and the waffle iron was furious. It looks kind of crazy, of course. But it does take the edge off cold reality. And sometimes it turns into real stories."

In another essay from the collection, Jackson, whose quirky sense of humor too often goes undiscussed in writings about her work, refers to these eccentric imaginings by the term used by her children: "Mother's delusions." Despite the facetious name, she does not underscore the importance of these "delusions," both to take the edge off "cold reality," but also as a technique for coming up with fantasies that may one day become "real stories." She writes at one point that she does not have "any patience for those good people who believe that you start writing when you sit down at your desk and pick up your pen and finish writing when you put down your pen again."

In "How I Write," she explains further how an author can use every minute to her advantage:

"One of the nicest things about being a writer is that nothing ever get wasted. It's a little like the frugal housewife who carefully tucks away all the odds and ends of string beans and cold bacon and serves them up magnificently in a fancy casserole dish. A writer who is serious and economical can store away small fragments of ideas and events and conversations, and even facial expressions and mannerisms, and use them all someday."

These stories and details didn't stay in her head, though. Jackson was also an avid note taker, who left pads of paper and pencils scattered around the house so she could jot down if a plot detail or character name or any other significant breakthrough hit her. Once she was ready to use these haphazard notes, she'd collect them all (she would leave them scattered around the house, all written in her own version of shorthand dialect and often addressed to herself), and attempt to figure out what she meant by it.

Let Me Tell You by Shirley Jackson, $12, Amazon

"Like many creative thinkers, Jackson thrived amid chaos," Franklin writes in the foreword to Let Me Tell You. "And her files mimic her overstuffed desk: pencil sketches and watercolor paintings; meticulously kept diet logs and appointment calendars; postcards, magazine clippings, and other visual sources of inspiration; multiple drafts of novels and stories; scattered dreams notes and diary entries, often stashed among the pages of whatever else she was working on at the time; even Christmas and grocery lists..."

Within the five lectures on writing found within Let Me Tell You, Jackson imparts a good deal of advice that will speak to the daydreamers among us and those who feel as though there is never enough time to sit down and properly think out a story. As Shirley Jackson so beautifully explains, there is always time to create a story, as the writing begins in your head, then travels to the page.