Entertainment

‘Slumdog Millionaire’ Is Not The Tribute To Indian Cinema I Thought It Was 10 Years Ago

I found a good number of reasons as an Indian person growing up in America — especially someone who loves movies — to attach myself rather blindly to a film like Slumdog Millionaire, now celebrating its tenth anniversary. At the time, my 18-year-old self felt its success represented a breakthrough for Indian talent in Hollywood cinema, and in some respects it certainly did. A decade removed however, the troubling legacy of Slumdog Millionaire reveals a film that is hardly a breakthrough of anything, and instead provides yet another example of a continued Hollywood tradition of condescending portrayals of developing countries like India.

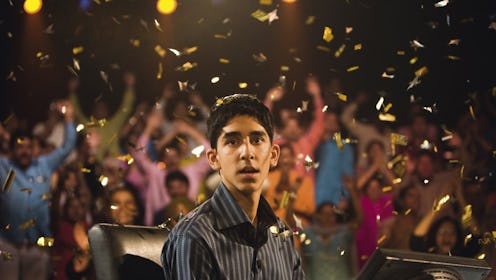

The initial positive energy surrounding Slumdog was very much tied to the fact that its production history, as chronicled by The Playlist, was its own Hollywood underdog story. Its journey from being an almost straight-to-DVD throwaway to winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards was as miraculous as its central character’s rags-to-riches story, if not quite as spiritually predetermined. Loosely based on the novel Q&A by Vikas Swarup, the film follows a young man named Jamal (Dev Patel) as he answers questions as a contestant on Who Wants to be A Millionaire? and has flashbacks as each question is answered by particular events in his journey from childhood to adolescence.

The story was intriguing to me, and the frenetic camerawork and fast-paced editing made the film both wildly entertaining and brisk feeling, despite its two-hour runtime. I remember watching the movie several times — with my parents, with my friends, and even in a college film class where my professor showed it during syllabus week. Looking back, the social and cultural problems director Danny Boyle’s stylistic choices played into didn’t necessarily elude me, I just purposefully blocked them out.

It was obvious early on that the film was problematic, as the reception to it in India, my country of birth, was far from welcoming. Anger at the film’s reported exploitation of the country’s impoverished neighborhoods was augmented further by claims that the cast of children, almost all whom were from slum neighborhoods, did not benefit in any meaningful way from the film’s success, per The Telegraph. (A Fox Searchlight spokesperson responded to the backlash claiming that the children were paid a salary three times what an adult in that area might earn, and Boyle stated that the production also established trust funds for the young actors and subsidized their education.) My dad’s own commentary on the film right after watching was something akin to, “Of course this movie is popular in America, they love watching poverty in other countries.” I shook it off, still wholly bought in by the fact that this movie was bringing Bollywood film actors like Irrfan Khan and Anil Kapoor and music composer A.R. Rahman, who’s music I’ve enjoyed for more than a decade beforehand, into the mainstream American zeitgeist.

One of the difficult balancing acts for people of color when watching movies representative of their race and culture is feeling pride in the fact that they’re seeing people like them on screen while still being skeptical of the actual social undertones of that representation, when many of the decision makers are white. It’s the reason why Moonlight being directed by a Black filmmaker like Barry Jenkins is essential to its authenticity.

The industry’s snide portrayals of non-white people and cultures has been a time-honored tradition since early films like the incredibly racist Gunga Din (1939). When it comes to India, Hollywood’s depictions center in on a binary, either fetishizing the country’s religious history as a spiritual awakening for a rich character as in Eat, Pray, Love (2010), or exploiting its poverty for dramatic effect such as in Slumdog Millionaire. Danny Boyle and screenwriter Simon Beaufoy’s visual choices in depicting India are particularly tasteless because they treat the poverty that the central characters grow up in as a third-world amusement park which inflicts suffering on them while delivering a voyeuristic adventure for his audience.

I compare that depiction with a film I saw in college later on: Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay, an Oscar-nominated Indian film from 1988 which also centers on a coming-of-age story of slum children in Mumbai. The difference that jumped out at me was that Nair, an Indian filmmaker, highlights the humanity of her child characters first and foremost. While Boyle introduces us to the city of Mumbai in Slumdog Millionaire with a kinetic sequence of kids running through a slum neighborhood dodging an obstacle course of sewage, garbage, stray dogs, and shanty homes, Nair showcases her main characters working odd jobs, scheming for food, and finding glimmers of joy in playing cards on the street-side. The film is clearly focused on helping the viewer empathize with who they are as people, and recognize the humanity in their daily routines. They are not reduced to being objects, running and jumping for my entertainment.

Salaam Bombay was only one of a number of other Indian films which opened my eyes to the fact that while the depiction of poverty in India is necessary in movies aiming to touch on the social and economic state of the nation, there is a responsibility of not using the poverty for the sake of exploiting its citizens. Even Vikas Swarup’s novel, told from a first-person point of view, reads more as a whimsical tale of self-realization than Slumdog Millionaire, which completely detaches from the genuine familiarity with “Indianness” Q&A portrays.

My re-evaluation of Slumdog Millionaire came through the knowledge that having grown up on Hollywood cinema conditioned me to assume things about the rest of the world through Hollywood’s lens. How different would I have initially taken Boyle’s film had I grown up in India, watching mainly Indian cinema? It became clear to me that Slumdog’s success in America came from a place of ignorance and lack of exposure to actual Indian cinema. With the advent of streaming services, it is now technically easier than ever for American audiences to see Indian movies, but they’re never promoted to the mainstream. The only place I know of that keeps a running tab of currently streaming Indian films is Access Bollywood.

Take a look at that list. How many of those movies have you ever heard of and knew were on Netflix right now? Couple this with the fact that Indian films hardly get any attention in the press from film critics or publicists (when was the last time you saw an end-of-year Top 10 list with an Indian movie on it?) and we can see why a film like Slumdog Millionaire can be mistaken for being an authentic “Indian” product.

The most direct way to remedy this gap — and the gap that exists between Hollywood and other countries' film industries as well — is to promote by word of mouth. If you happen to see a movie from another country that you really like, make it a point to tell people. If someone recommends a foreign film to you, make it a point to at least seek it out on IMDb or watch its trailer. Five of my favorite Indian films (and that doesn’t necessarily mean “Bollywood" films, by the way) that are available on Netflix right now are Lagaan (2001), Dhobi Ghat (2011), Udaan (2015), Mughal-e-Azam (1960), and Miss Lovely (2015).

Diversity of viewpoints and authenticity of source is what will ultimately de-mystify stereotypes and cultural misconceptions. For as popular as the film was and is, Slumdog Millionaire’s ability to be an entertaining romp should not mean it's considered to have even a shallow understanding of India’s economic history or social issues.