Books

Start Reading Ilze Hugo's 'The Down Days' Right Now

If you've been looking for your next literary science-fiction read, look no further, because you can start reading Ilze Hugo's The Down Days right now, exclusively on Bustle. This debut novel from South African journalist Hugo takes place in a near-future Cape of Good Hope, seven years after a fatal laughter epidemic tore society down to its roots. The Down Days is out on May 5, 2020 and is available for pre-order today.

In 1962, a real-life laughter epidemic swept through Kashasha, Tanganyika, in what is now Tanzania, striking hundreds of people with uncontrollable laughter over its months-long course. The laughter in The Down Days is more sinister, with the sick — known as "grinners" — turning to mush as their disease progresses.

Seven years after the laughter began, everyone in South Africa wears a mask. People have grown increasingly paranoid about catching whatever the illness is, and new symptoms, including widespread hallucinations, have appeared. Are the fear and false visions merely an extension of the original sickness, or is another wave of mass hysteria about to hit the Cape of Good Hope?

A former minibus taxi driver, Faith now works as a collector of corpses, while Tomorrow barters for food to keep herself and her baby brother, Elliott, alive. When Elliott is kidnapped, Tomorrow turns to Faith for help, but the driver can't help but wonder whether the boy might not just be a symptom of Tomorrow's hallucinatory illness.

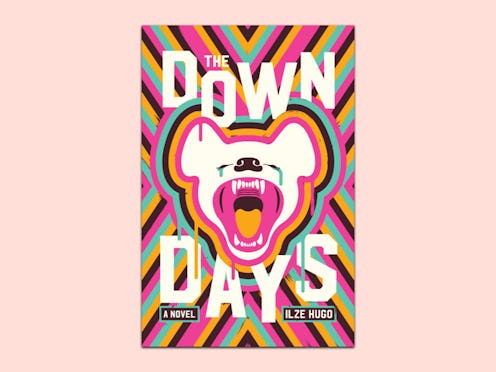

Keep scrolling to get a first look at the cover of Ilze Hugo's The Down Days and start reading now before it hits shelves May 5, 2020:

Monday, May 13

The Daily Truth: Opinion

We Remember by Lawler Tshabalala

It started with a tremor, small and unassuming, as these things generally do, my broe. Just a few words on page seven (by yours truly) about three tween girls stuck in a giggle loop. The school called in a bunch of experts, who gave the thing a fancy label. And this put the parents’ worries to rest. Because who doesn’t like a good label to help them sleep at night?

Mass psychogenic illness. Also known as mass hysteria. Just a couple of tweens with their hormones running riot. Nothing to worry about. It had happened once before. In the sixties, in Tanzania. Remember the Tanganyika laughter epidemic? And that story turned out fine. No need to panic, run tests, stick needles into anyone.

The experts took the Tanganyika epidemic as a blueprint and ordered the girls to be isolated from their peers. So, the school sent the girls home to ride out this wave of runaway emotion somewhere else. Case closed, problem solved, job well done. Only thing was, it didn’t work. The girls didn’t stop laughing. Four days passed and the girls were burning fevers now. Struggling to breathe, eat, sleep. One by one they were rushed to the emergency room. Test after test was run while they lay shackled to their beds to stop them from falling off. Fed through tubes, attached to breathing apparatuses, and monitored around the clock.

Seventeen days. One day longer than the worst of the cases reported in the Tanzanian epidemic. And the girls were still laughing. Eyes tearing, voices broken, mouths salivating like mutts, faces contorted in the most horrific grins, knees jerking, arms flailing, bodies forever convulsing like crash test dummies.

Meanwhile, the “joke” was catching. The girls’ families started laughing first, then their friends, their coworkers. The nurse with the heart tattoo on her ankle who came in quick to change the IV drip. The car guard holding out his hand for tips.

At first the guys upstairs clung to the mass hysteria diagnosis and tried to stem the tide by closing all channels of information. Lawyers were hired to file DMCAs to stop people from streaming all those YouTube clips or posting images in their feeds on social media. This was the Information Age, after all, and the tide couldn’t be turned. So, the government pulled rank, imitated their chums in China, and orchestrated a total web blackout. Our city became data dark. But like Adam and Eve, we couldn’t go back after tasting from the tree. Social media addicts were up in arms, their trigger fingers were itching and twitching, and a new kind of violence, dubbed “withdrawal rage,” swept the masses. Addicts would snap and bring out their fists for as much as a skew look in a queue, and violence stats soared.

And along the way, more and more people were cracking up. It’s psychological, it has to be, the experts proclaimed: an extreme response to Third World stressors.

But the girls, the ones the Laughter had chosen first, were now showing other symptoms, too. Their bones disintegrating, their organs turning into soup. And this thing, this mass collective joke, was blowing up in everyone’s faces, with laughter resonating on every street corner, and death following suit.

Today, exactly seven years on, we remember the day that changed our sick city forever. Dorothy, Jennilee, and Andiswa: may you rest in peace. Along with every single soul who followed after. And God, Allah, Vishnu, the government, our ancestors (or whoever we choose to believe in) help us. May we one day find a cure for this curse.

Faith

Faith September sat waiting behind the wheel, staring through the windscreen. Outside the wind was playing tennis with an empty crisps packet. A mottled seagull dipped and dived, trying to nip at it. As the number one driver for the Hanover Lazy Boys Corpse Collection Association, Faith spent her shifts on the streets of Sick City. Her guardjie and general sidekick, Ash, was a stringy white boy with a mullet who was in the habit of spinning tall tales and called his 9mm his baby.

In her life before the Down Days, Faith drove a minibus taxi. A tough job, with pay-as-you-go — or as many fares as you can load — wages. Time was money, every second wasted was a fare lost, and passengers had to be squeezed in fast and tight, skin on skin, like Tetris blocks. This led to some hairy driving to make ends meet and lots of name-calling from pissed-off passengers and motorists who didn’t understand the challenges of the job and would scream and moan and call minibus drivers all sorts of names, like bastards, lunatics, cowboys, and cockroaches.

Then the Down Days came, and many taxi companies expanded their business into the epidemic industry, pimping their minibuses to move coffins instead of customers. As it turned out, the dead paid better than the living (and never complained about sharing seats) and this cockroach was now quite literally living the high life with a sky-scraping pad perched above the ocean in Clifton and a full tank of petrol whenever she needed it.

That wasn’t to say her life was all roses, though. Carting the dead around was backbreaking work and distraught mourners would often throw things, scream at her, chase her away, or call her all sorts of names, like grim or vulture or hyena. But Faith had come to accept that grief wasn’t rational and couldn’t be argued with, so she just put her head down and got on with it. That said, sometimes there was respect, too. Every now and again a stranger would stop her in the street, call her Charon (after the mythical ferryman who carried souls over the River Styx), and give her a brown coin as a token of appreciation for the work that she did.

Ash was at the market, hunting for air freshener and taking his own sweet time. A girl, no more than a child, crossed the street, pushing a rusted trolley. The girl tugged at the ears of her cutesy teddy bear medical mask, the trolley’s wheels going squee-squee as they rolled over the tar. Startled, the gull fled upwards, leaving the crisps packet behind. As the girl lifted the trolley up and onto the pavement and disappeared into the folds of the Company’s Garden, Faith stroked the bruise above her right eye. The damn thing was tender as hell and throbbing like techno.

Earlier that morning, while playing cards in the square, they’d been called to the home of a preacher who had promised his congregation that he would raise their dead. “Just wait four days,” the sanguine pastor had apparently proclaimed, “and your loved ones will rise and walk among you again.”

Four days had turned into four weeks.

The cops were called when the neighbors started complaining about the smell. So they raided the preacher’s house and found grinner upon grinner stacked next to the TV set. When Faith and Ash came in to load the smiling corpses, the congregation was fuming and a riot was brewing.

The smell of the mob: fear, rage, adrenaline, sweat.

Stones were thrown (hence the ugly purple bruise), along with a couple of eggs. The cops retaliated with tear gas.

When they finally had all the grinners packed in the van and Faith started the engine, her back killing her, Ash began retching, just barely making it out the window. “Sorry, boss,” he’d said. “It’s the gas, it always does this to me.”

After leaving the coroner, they could still smell the sick, so Faith sent Ash to the market for air freshener. She opened her window a crack. In the rearview mirror she studied the file of rusting metal carcasses lining the shoulders of the road: car upon deserted car whose owners had flown the coop, kicked the bucket, or couldn’t afford the skyrocketing price of petrol and opted to skateboard, cycle, hail one of the few remaining minibus taxis catering to the living, or use their feet instead. Some of the windshields were shattered, others thick with dirt and dust on which a hundred and one fingers had left their mark. “Wash me,” “Johannes was here,” “Cindy & Tamatie foreva.” Bright spray-painted imagery adorned others. A kid in a black hoodie was squatting on the roof of a beat-up Mazda, touching up the teeth of an image of a spotted hyena with a yellow spray can. The hyena was flashing its fangs, cold black eyes staring heavenward. The kid’s sunshine-yellow mask had a laughing cartoon mouth painted on it; a brave choice if she’d ever seen one. These days, folks were mobbed or rounded up by the Veeps — the Virus Patrol — for much less.

On the radio, the city’s only remaining nongovernment-affiliated station, run by a passionate group of volunteers, had an interview on with some woman from some organization. Faith didn’t catch the name — Citizens Against Something-Something-Something. She was being interviewed by the station’s husky-voiced midmorning presenter, Sandy B.

“It’s atrocious, simply atrocious,” the woman was saying. Her voice grated. “These kids need guidance. It’s simply unacceptable to have an army of orphans running amok. Children need parents, authority figures, discipline. And when normal family systems break down, the government needs to step in and provide us with a solution.”

“But,” Sandy B interjected, “we’ve all heard about the current state of these facilities. The government-run orphanages are filled way beyond their capacity. The system is failing these kids. So surely —”

“The system, any system, is darn well still preferable to the situation we have on our hands right now. I mean, every darn day this city is turning more and more into Lord of the Flies, what with these little hooligans on every street corner. Right this morning I caught one going to the bathroom on my daisies! My daisies, for goodness sake! Those bleeding-heart liberals who are moaning and groaning that the current welfare system is legalized child slavery should take their rose-colored glasses off and face facts. I mean, what about education? Who is teaching these street rats to read and write? Give it ten years and we’ll be thrown right back into the Middle Ages, with all these children, now adults, running the country when they can’t even spell. No. I say round up the little trolley-pushing tsotsis.”

“But new reports indicate the situation is temporary. That the French have developed a vaccine that should be in production quite soon. Following this, more schools will be opening their doors again and —”

“Please! Do you really believe that? Open your eyes! The West doesn’t care about us. They’ve closed their borders and left us here to rot. No. Something has to be done, come hell or high water. I say the government has to do its job, keep rounding them up and carting them off or else —”

Faith reached over and changed the station. The boy on the roof of the car put his spray can down and started fiddling with his phone. Then he slid off the bonnet and disappeared down a side street, passing a pair of kids busking on the curb. Kid number one was shaking a tin can to the beat while kid two was drawing dollar signs with a Sharpie onto the other’s free arm. The song their lips were churning was a hot ticket for busking street kids all over the city, although they never seemed to learn more than the first verse, which they belted out in sing-scream until folks plead-paid them to stop. These two were different, though. They seemed to know the words.

Faith reached for the knob and turned the radio down to listen:

We are traveling in the footsteps

Of those who’ve gone before

But we’ll all be reunited

On a new and sunlit shore.

Oh when the saints go marching in

When the saints go marching in

Oh Lord, I want to be in that number

When the saints go marching in.

And when the sun refuse to shine

And when the sun refuse to shine

Oh Lord, I want to be in that number

When the saints go marching in.

When the moon turns red with blood

When the moon turns red with blood

Oh Lord, I want to be in that number

When the saints go marching in.

Faith thought back to all those grinners this morning, stacked next to the TV set. How desperate those families must have been, to believe a crazy charlatan like that, saying he can raise the dead? She got it, though. Wanting to believe in something. She got it more than anyone. What with loading up grinners day after day, taking them away. Then there was that stupid suit. That canary-yellow cage. The way people stared at her when she was wearing it. Stepping back or averting their eyes when she walked past. As if she were death itself.

Not like any of this was new. Sick City had been delivered from the loins of the sick from the start. That’s what her mother had always said. That illness did more than sticks and stones to build and break this city’s bones. Scurvy was why the West first came to the Cape and brought slaves to these shores. Disease was behind the first seeds of segregation, too — the perfect excuse to give voice to silent prejudices. Way before the horrors of District Six, when the bubonic plague had raged through these streets, the homes of those deemed unwhite and unclean were razed to the ground. Their inhabitants chased to tented quarantine camps on the barren, sand-swept Cape Flats. If your skin was lily white, your home was merely disinfected and you were free to come and go as you pleased. If it wasn’t, you needed a plague pass to travel.

No, none of this was new. The cradle of humankind was also the cradle of guns and germs and death. All those little red flags on the map the color of blood. The soil here was thick with bones. This had always been a city shaped by germs. These streets were birthed by disease. And one day, it would be destroyed by it.

But not yet.

For now, most people are still getting by. Chins up, as Ash liked to say. Chins up. Where the hell was that kid anyway?

Tomorrow

Tomorrow was at the market, feeling up avocados. Pressing her fingers into each green skin to see which one would give. Finding the perfect candidate, she turned around towards her purse, which was resting in the belly of the rusted trolley where her baby brother, Elliot, was playing with a coffee tin.

These days the prices at the local supermarket were a punchline to some kind of bad joke, with most of the shelves standing empty, gathering dust. Queues for what was left stretched around the block. So Tomorrow preferred to do her shopping here, in the Company’s Garden.

The city’s green lung was a relic of Sick City’s days as a Dutch East India Company colony, when greens were planted to save passing sailors from scurvy. As if history was folding in on itself, the Down Days had led the locals to digging out almost all the pretty flower beds to plant vegetables again.

“How about this weather, né?” said the fruit vendor while adjusting her headscarf, dotted with fat little sausage dogs. “The wind’s being a right banshee today. I can’t stand it. And have you seen the mountain? All wrapped up in its shroud. Old Van Hunks and the Devil must be smoking up a storm again.”

“Yes, auntie, they sure must be.”

Van Hunks. The name made her think of her dad, who used to tell her the myth as a bedtime story: about this pirate called Van Hunks who used to live on the slopes of Devil’s Peak back when Sick City was still called the Cape of Good Hope. Van Hunks lived for his pipe. Every day he’d sit on top of the mountain, blowing smoke rings and watching the ships sail by in the bay. One day a stranger approached him there and challenged him to a smoke-off. Van Hunks said yes, and for three days, Van Hunks and the stranger puffed without rest. Day four, they were smoking up a storm when a gust of wind blew the stranger’s hat off, revealing the grooved and twisted horns of the devil himself. A sight like this would have had many a man choking on his own black smoke. But Van Hunks wasn’t deterred. He just kept puffing. And he still is, they say.

On days when the mountain is swathed in fog, the old folk know it’s just Van Hunks and the devil, still up there, smoking. Tongues smarting, lungs burning, neither ready to admit defeat.

Some say their duel has been going on for so long that they’ve developed a strange kinship. Together they huddle, spines curved into frowns like old men’s backs tend to do, watching the empty harbor that has long since stopped sheltering ships and the bodies going about their lives below, while the smoke billows from the bowls of their pipes. Never interfering, just watching. Watching and puffing and packing their pipes on repeat.

“So what do you have for me today, sweetie?” the fruit vendor asked. Tomorrow bent double to retrieve the bag tucked away underneath one of her brother’s plump legs. Zipped it open and retrieved five glass jars. “For your pickles.”

“What about the eggs?” the vendor asked, her brow knotting into a frown.

“Sorry. Not today. A mongoose got into my hens.”

The lines above the vendor’s threaded eyebrows smoothed out. “Not what I was hoping for. But we can work with it. Here.” Her hands reached across the table. In each cup of flesh rested one green potbellied fruit. “Take two.”

The girl scooped up each ripe avocado and placed them in the trolley next to Elliot. “Thank you. I’ll do better next time.”

The vendor smiled, one hand tugging at the hem of her glove. “You have a good day now, you hear? And cover up that poor boy, will you? Or next thing you know, he’ll be blown away with the wind.”

Tomorrow grinned, happy as a Cheshire cat that the woman had noticed the boy. Elliot was a funny kid, quiet, in his own world, easy to overlook. He tended to slip through the cracks and this worried her sometimes.

“Yes, thank you, auntie, I will. See you next week.”

“As-Salaam-Alaikum, my kind.”

“Wa-Alaikum-Salaam.”

The girl and her baby brother headed up through the garden’s old aviary, which was now a thriving chicken coop. “Cluck-cluck-cluck,” prattled the toddler, pointing a finger at the fat hens as they dug in the dirt. A loud bang cut through the air as the city’s daily med cannon fired, frightening the hens and the boy, who emitted a loud howl. Tomorrow kissed the boy on his head, gave his cheek a quick pinch. “There now, my sweets, no need to cry. Look, look! A squirrel. Let’s follow him. Come!” The boy swallowed his howls, pointed gleefully at the squirrel, and the girl pushed the trolley further.

At the far end of the garden was the steps of the Iziko South African Museum. The old colonial edifice loomed over them like a goliath’s wedding cake. Slathers of white icing framed the yellow walls.

After the tourists had left, and the museum’s funding had dried up, the artifact-stacked rooms became an informal mass garage sale, where locals bartered for odds and ends, from toothpaste and chlorine to homemade toilet paper and fried pigeon kebabs. A year ago, the World Food Programme and other international-aid programs had used the museum as a base to distribute food, formula, and rations. But suspicion, fueled by the endless pick of crackpot and not-so-crackpot conspiracy theories that bred like rabbits in these kinds of times — that the Laughter was a plot by either the government or the nebulous “West” — had resulted in mob-led beatings and the odd sjambokking of aid workers. Many of them had since given up on the cause and left. The wall to the left of the entrance was scarred with paint from a previous protest turned violent. “Stop poisoning our children! Death to all imperialists!” the bloodred-painted letters proclaimed. Next to the exclamation point, a queue was forming in front of the museum’s red medmachine. On the other side of the big brown museum doors, a government cleaner in a puffy Tyvek suit was spraying the ground with bleach.

“Come, my little penguin,” Tomorrow cooed into the trolley.

The boy looked up, blew a raspberry, and went to work again, banging the coffee tin like a drum. The girl lifted him out of his metal cage, slung him across her hip, tin and all, and pulled the trolley up the stairs behind them, grunting with the effort. She fiddled around in her bag till she found the two plastic medpasses, and the two children waited patiently in the queue for their turn to get checked. Then the big brown museum doors swallowed them with a gulp.

Inside, spread out underneath the suspended ribs of a giant southern right whale skeleton, the museum was a trickle of activity. Below the leviathan’s broken umbrella of bones, a motley straggle of figures milled about between the tables strewn with things while the dead presided over proceedings from the safety of their glass coffins, their black pretend-eyes betraying nothing. The air had a chill, and the trolley bar felt cool in Tomorrow’s palm. TRY SOMETHING NEW TODAY, read the ad prattle on the bar.

The girl tugged at the beanie on her brother’s head, pulling it down to cover his ears. He gurgled at her as she pushed past a snarling taxidermy gorilla balancing on its hind legs. Someone had thought it funny to dress the poor animal in a yellow health-worker suit, complete with goggles, gloves, and mask. The new garb made the creature look more embarrassed than fierce, but the stuffed monster still left Tomorrow ill at ease.

She pushed harder; the trolley rolled faster. A funny-looking guy with a mullet squeezed past her, gripping a can of purple air freshener. What a weird thing to spend your money on. Who had the cash to spare to make sure their farts smelled nice? Why couldn’t he rather spare a rand or two for her, instead of spraying it away into the toilet bowl?

“What a cute kid.” A woman stopped to bend down and pat Elliot’s head. There was a tattoo on her wrist. A snake curling around a stick. Her bottle-red hair needed a wash.

Tomorrow gave the woman a quick nod (polite smiles were pointless now that everyone wore masks) and forged on, past cabinet after cabinet of forgotten yesterdays. Rows of frozen corpses that, although already dead much longer than she’d been alive, still seemed ready to pounce.

A family of foodists stopped her to peddle their sales pitch, which was all about eating like a monk and humming a lot in order to live into your hundreds. They were handing out little pink pamphlets and selling all sorts of weird supplements in little hand-labeled bottles, from organic bee pollen to caterpillar fungus to colostrum from preservative-free moms.

Tomorrow found the stall she was looking for squeezed in between a tall Sikh selling paraffin and a muthi stall whose youthful proprietor was singing to himself underneath a nylon clothesline strung with dried black cats, anaconda skins, herbs, hippo tails, and horse legs.

While the bug-eyed vendor gossiped with another customer — something about a mutual acquaintance who had recently gone full hermit from the paranoia, only leaving his apartment once a week to throw out the trash — she picked up the bag of sugar. Looked at the price. It wasn’t cheap. But it was her birthday and it had been ages since she’d last baked anything for the two of them. “Feast when you feast and fast when you fast,” her dad had always said when he was still around.

Decision made, she turned towards the trolley to tell Elliot about the cake and how she was going to decorate it. Red — she’d use red icing, his favorite color. Sure, it would look a bit garish, but...

There had been a street magician who stood on a wooden box outside their house sometimes — their old house, that was — and bartered coin tricks for whatever you had to give. He also sold Ziploc bags of Ethiopian coffee beans, which his wife would roast in a pan at her feet, then grind, steep, pour for you into a small blue cup, and sprinkle with salt. But his passion was coin tricks. She knew by the smile he tried to suppress each time a kid would gasp or their mother drop a slack-jawed chin when they gave him a rand and he turned it over in his hand, blew on his palm, and then opened it with a quick flutter of his fingers like a startled dove — and the coin was gone.

Tomorrow used to love watching him, hoping for a glimpse of the vanishing coin that would betray his act. But she never did spot it — the man was too quick.

She would think of him afterwards, when she replayed this moment in her brain. Remembered her cold shock, the optimist in her convincing herself that the empty trolley was a silly trick, a sleight of the brain. A joke. That someone must have picked Elliot up to coo at him. They’d gone for a quick walk to show him the fluffed-up rabbits curled into the corners of their cages down the aisle, but they’d bring him right back.

They would. Sure they would. Any second now. Any.

Second.

Now.

Ilze Hugo's The Down Days is being published by Skybound Books on May 5, 2020.

This article was originally published on