Books

Your Favorite Insta Poet Just Released A New Collection About Female Anger & It's A Must-Read

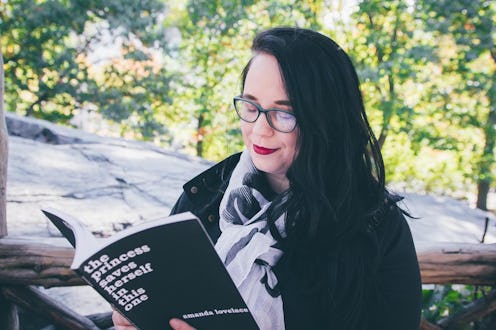

She’s a member of the now-iconic cohort dubbed “Instagram poets” — who, alongside writers like Yrsa Daley-Ward, Nayyirah Waheed, and the bestselling Rupi Kaur, are filling both books and social media with accessible, relatable, and dare I say trending verse. A 2016 Goodreads Choice Award-winning poet, Amanda Lovelace is a name you almost definitely recognize, whether or not you’re as poetry-obsessed as I am; and if you loved her debut collection, The Princess Saves Herself In This One, chances are you’ve been waiting for what comes next.

Good news: your wait is over. Out March 6 from modern poetry powerhouse Andrew McMeel, The Witch Doesn’t Burn In This One is the second installment of Lovelace’s Women Are Some Kind of Magic series of poetry collections that take some of the most recognized female archetypes — princess, witch, and soon, mermaid — and retells their narratives in a modern, feminist, empowered way.

“If there’s one thing I’m trying to do with this particular poetry series, it’s to show the rich inner lives of women with a focus on our hidden everyday struggles,” Lovelace tells Bustle. “The way I view it, The Princess Saves Herself In This One is about child abuse and survival, The Witch Doesn’t Burn In This One is about anger and rape culture, and The Mermaid’s Voice Returns In This One [the third title in her poetry series, slated for publication in the spring of 2019] is about sexual trauma and healing. These aren’t the only issues women face, and women certainly aren’t the only ones to face them — far from it. I’m just trying to call attention to one of the many unique perspectives that have been silenced for much too long.”

The Witch Doesn't Burn in This One by Amanda Lovelace, $12, Amazon

Where The Princess Saves Herself In This One is a poetry collection filled with autobiographical pain, subtle strength, and quiet resilience, The Witch Doesn’t Burn In This One is, not ironically, filled with fire. It’s angrier than The Princess Saves Herself In This One, filled with passion, power, and rage: Lovelace writes about “mother-rage," “woman-rage," “woman-rage-fire” — perhaps, in part, a reflection of the way that, from #MeToo to Time’s Up, the energy of women in the world has shifted between when The Princess Saves Herself In This One was first published in April of 2016, and now. But, as Lovelace describes, it’s also the natural and welcome consequence of a poet finding her stride, fully arriving in the literary space she inhabits.

"If there’s one thing I’m trying to do with this particular poetry series, it’s to show the rich inner lives of women with a focus on our hidden everyday struggles."

“While I was writing The Princess Saves Herself In This One, I was constantly afraid to come off the wrong way in case people got the wrong impression of me,” says Lovelace, who first self-published the collection before it was picked up by Andrew McNeel. “That’s why the book ended up taking on such a sorrowful tone. Even if I had the right to be angry about the abuse and trauma I had endured for most of my life, it’s still seen as unbecoming for a woman to express herself in such a brash, unapologetic way. Unattractive. While I was writing, I had two choices, and I took the path with the least resistance. There’s a little anger here and there, sure, but I was still holding myself back so I didn’t ruffle anyone’s feathers.”

The Witch Doesn’t Burn In This One is decidedly different. I ask Lovelace how she navigated the rage that comes alive in the collection, throughout her writing process, and if she sees that the cultural space held (or, you know, historically not held) for women’s rage is shifting right now.

“If I learned anything from Princess, it’s that it’s not conducive to keep your emotions and experiences locked inside yourself, and with the slow build of the #MeToo movement, I knew what book I had to write,” explains Lovelace. “It was going to be angry. It was going to be blunt. It was going to make most people uncomfortable. But that’s where conversations start — in this discomfort. Witch isn’t even fully out into the world yet, and it’s already starting some much-needed discussions. This permission we’re giving to ourselves as survivors to not only be privately angry, but also publicly angry, has been liberating for us all.”

One thing readers might be surprised to learn after reading The Witch Doesn’t Burn In This One — a collection that speaks so explicitly to our current moment — was that Lovelace actually completed the book before the Twitter revival of the #MeToo movement. “Leading up to the 2017 version of the movement, change was in the air. Slowly but surely, people were speaking up about their attackers and harassers, as well the rape culture-infused climate that was shaping us all. That bravery, that fearlessness drove my will to write. Despite the timing, Witch is still very much my #MeToo book. It will also not be the last one.”

"It was going to be angry. It was going to be blunt. It was going to make most people uncomfortable. But that’s where conversations start — in this discomfort."

Lovelace also cites being influenced by books like Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak, All the Rage by Courtney Summers, Exit, Pursued by a Bear by E.K. Johnston, and After the Fall by Kate Hart. The collection is also filled with more literary references, from the ever-relevant The Handmaid’s Tale, to Grimoire for the Green Witch, to the musical Hamilton, the 19th century English poet Christina Rossetti, and timeless characters like Dorothy and Lilith.

Other than the fact that both of Lovelace’s current collections exist in her Women Are Some Kind of Magic series, the collections also seem to work together towards a larger aesthetic — almost as though the poet’s princess and witch are in conversation with one another, learning from one another's narratives, existing in a kind of progression, one evolving beyond the other.

“I think they both work for and against each other,” says Lovelace, of the collections. “Princess is almost flowery, easy-to-digest feminism. There’s nothing wrong with it, but it’s just a foundation. A beginning. Witch, on the other hand, builds on top of that foundation, and it’s more in-your-face feminism without watering down any of the normalized violence women are faced with. Witch, in a strange way, is almost the anti-Princess. They both hold their respective places, but I do feel the witch is the more mature version of the princess.”

Then, there’s Mermaid — the third and forthcoming archetype Lovelace fans have to look forward to.

“Mermaids are hypersexualized creatures, and for what feels like since the dawn of time, we have told stories about sailors being lured into the sea by their bare breasts and seductive songs,” explains Lovelace, when I ask her what other female archetypes she’s eager to explore in future collections. “Even the symbol for a popular coffee company is a twin-tailed mermaid. Another way of looking at it is that her tail has been split in half. But why? In search of what? Whatever object of desire they believe she’s hiding when her tail is closed as one. The lesson is that mermaids — or women, since that’s what we ultimately view them as — are defined not by the strength of their voice but by how they can fulfill the sexual urges of men.”

Though Lovelace is still working on The Mermaid’s Voice Returns In This One, she says she’s continuing to explore the theme of rape culture that she began in The Witch Doesn’t Burn In This One, while returning to the personal narrative that The Princess Saves Herself In This One features. “Mermaid is how I learned to sing,” says the poet, “and how that means something different for different people, all of them valid.”

Of course, I have to ask her about her status as an “Instagram poet” — a phenomenon that readers love and poetry traditionalists love to hate, in equal measure. But love it or hate it, there’s no denying that the poetry going viral on social media is not only bringing more readers to the genre, it’s also changing the way poetry is written and read, and who is being invited to read and write it as well.

“When you ask people what they think of when you say the word ‘poetry’, the responses usually aren’t favorable. For most of us, reading poetry during our formative years was a painful experience, outside of nursery rhymes and playground songs,” Lovelace says. “Often, it was too difficult to interpret and analyze since it restricted itself by having too many rules, and what’s fun about rules? It seemed to be written only for the elite — not the everyday reader, and certainly not children and young adults.”

Social media, and writers like Lovelace, are changing all that. “What social media outlets like Tumblr and Instagram have done is finally make poetry understandable,” she says. “Old school poetry lovers claim ‘Tumblr Poetry’ and ‘Insta Poetry’ are too simple to be considered 'real poetry', but I don’t see anything wrong with being transparent. There’s something to be said for a writer who’s able to take only a handful of words and cause an emotional chain reaction in thousands of people. That’s not something everyone is able to do. Structure takes precision and talent, and so does simplicity, just in a much different way.”

"There’s something to be said for a writer who’s able to take only a handful of words and cause an emotional chain reaction in thousands of people."

Not only is Lovelace invested in making reading poetry accessible to a wider community of readers, she’s also helping forge space for a wider community of writers — going so far as to actually leave a physical space at the end of The Witch Doesn’t Burn In This One with an invitation for her readers to “write themselves in”.

“The genre is having a major shift,” Lovelace says. “Which can be frightening for some, especially if that isn’t their chosen style, but I think there’s room for every kind of poetry — short, intense poetry is just the type of poetry people are responding the most to right now. I think what we need to remember, above all, is that accessibility is actually a positive thing, and that change is necessary if we want poetry to survive the test of time.”