Entertainment

There’s Actually A Scientific Reason For Why You’re Obsessed With True Crime & Cooking TV Shows

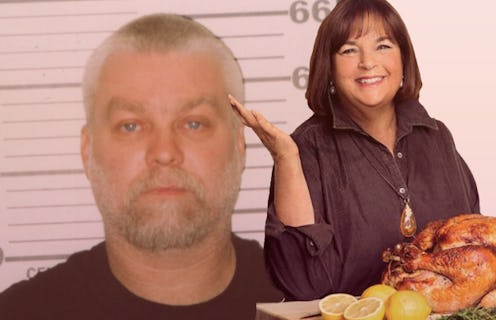

During the golden age of TV, no two genres have proven to be more engaging than murder mystery and food-related series. According to Symphony Advanced Media, 7.8 million people watched the finale of Making a Murderer within a month of the series dropping on Netflix; 10 days after the premiere; "nearly one in five adult television viewers were tuning into the show." Meanwhile, in 2015, Fast Company noted that "YouTube's cooking vertical has approximately 800,000 videos with over 11.5 billion views across approximately 118,000 channels," and the number has only risen since then. As more and more viewers get pulled into the darkness of Big Little Lies or the food-centric world of Parts Unknown, for instance, questions arise: is our obsession with true crime TV correlated to our love for food-based programs? Do food and goriness tickle the same parts of our brains?

According to experts, yes — and it's all about dopamine. Although higher levels of the brain chemical are typically associated with pleasure-related events like orgasms and the consumption of delicious foods, “if you look very closely, [dopamine levels] actually spark right before the thing that makes you feel good [happens], because anticipation is what causes the spike," explains New York-based clinical psychologist Donna Peri, speaking over the phone.

And when something unexpected occurs, that anticipation heightens. “So [with] these murder mystery shows, and even the cooking shows, the more nuanced the topic, the more exotic, the more different it is and the more novel it is, the more we anticipate and the better we feel," says Peri.

In simpler terms, despite dealing with completely different themes, the two TV genres interact with our brains in similar ways: they both make us feel excited. Trying to figure out whether Brendan Dassey was wrongly jailed actually jolts our dopamine levels, and the same thing happens as we watch a meal get prepared on Barefoot Contessa.

Yet there's also a connection between the genres that goes beyond a classic biological narrative and has to do with social norms — specifically, flouting them. “There is a Freudian concept [called] sublimation, by which we take an unacceptable urge and channel it into something that is more socially acceptable,” explains Peri.

Take those suffering from eating disorders, for example. “We often see that the people who are so restricted in their eating are becoming very obsessed with cooking,” says Peri. “So we always ask a patient’s parents if they show a new interest in cooking and feeding other people and often, the answer is yes. So, one theory [for someone's love of food TV] is that a person, instead of consuming the calories, [is] obsessed with them in another way.”

Of course, not everyone who religiously watches Ina Garten prepare holiday meals on TV suffers from an eating disorder. But the theory does shed light on a larger psychological truth: we're drawn to shows that depict environments, behaviors, scenes and lifestyles that we want to make our own. A desire to pursue a career in criminology or journalism might propel an obsession with Making a Murderer, for example. Constant dieting or a keen interest in hospitality may be redirected into nightly viewings of The Best Thing I Ever Ate.

Our avid embrace of each genre also acts as a display of the kinds of passions, interests, and preferences that may not show up in regular life. For instance, we might never have baked, yet find ourselves setting our DVRs to every episode of Cake Wars. These shows sometimes portray our ideal lives, and ultimate goals. In other words, they're fantasies.

Some viewers recognize the reasons behind their interest in these shows. "I wish I was either a cop or a chef. I wish I was either Olivia Benson or Giada De Laurentiis," says Natalie Ashoory, a New York-based brand manager obsessed with Law & Order: SVU and Vice's F**k, That's Delicious, speaking via phone. "So it’s pretty amazing that [through TV] you can kind of participate from afar in something that you would never, ever, ever do, which is either kill somebody or tour the world eating your way through it.”

Yolanda Evans, a freelance food, drink and travel writer who proclaims to be "obsessed with these types of shows" right off the bat, echoes Ashoory's sentiments in an email: "I don't work in crime but, when I was in college, I thought I wanted to be a crime reporter. I couldn't handle the blood and gore." She eventually found herself redirecting her predilections, applying them to her DVR recordings: "Now, I write about travel and booze and just watch the stuff on TV."

Copywriter Jasmine Dilmanian has her own reasons for loving these programs. “Mystery addicts you like no other genre can. You become so personally invested that you physically can’t stop watching until there is a resolution or, at least, another cliffhanger,” she explains. “With food, it’s also about addiction. It’s also about tickling your other senses while you’re in front of the screen.”

We tune into shows that deal with colorful foods and captivating mysteries to escape our own lives and glimpse supposed better, more exciting words that we might want to be our own. Yet, when pitted against the delicious bowls of pasta and enthralling real-life mysteries that define our very own realities, simply watching others do — whether it's Bourdain traveling to Iran or Jonathan Groff's character sitting down with serial killers on Mindhunter — starts feeling less exciting.

And when analyzed against the history of TV and the trends that have defined generations of couch potatoes, a dark pattern emerges. “In the ‘50s, shows like I Love Lucy were big on identification,” says Peri. “But [current programs] have moved away from identification and affiliation. They’ve gone from shows that make you feel good to a show that allows you to escape, that allows you to zone out so badly that it could be not good for you.”

At the very least, viewing this kind of TV can bring out our more hidden tendencies. “When I think about what attracts me to this type of television, I can’t help but think about the seven deadly sins," says Ashoory. "Essentially: vices: what are the things that make us want to tap into these forbidden pleasure zones and more sadistic sides of our personalities in order to ultimately come out of it with a little surge of euphoria?"

Ashoory also notes that her TV viewing habits feed into her "intellectual sloth side," a part of herself that she typically keeps hidden. And the same is likely true for many viewers of so-called fantasy TV. Sometimes, it seems, staying put might be better for us than constantly looking away.

This article was originally published on