News

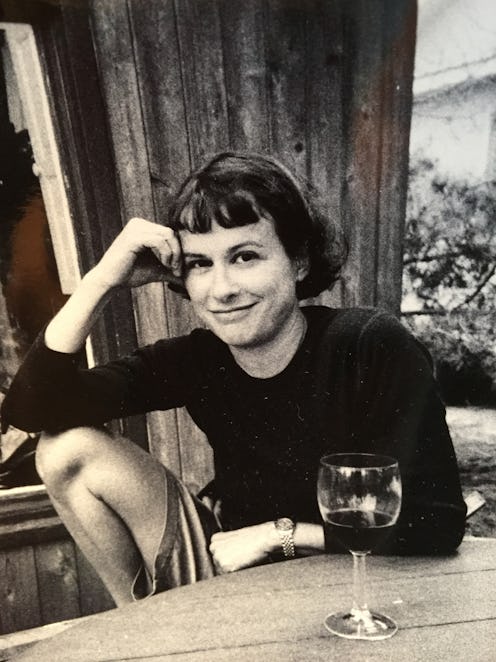

Without This Woman From A Novel, I Wouldn't Have Changed My Own Story

"I am so tired of it, and also tired of the future before it comes." This epigraph by 19th century South African writer Olive Schreiner is how Doris Lessing opens the first Martha Quest novel. Standing in the stacks at the public library, holding the book in my hands, I was hooked.

I found Martha during one of my life's doldrums. I waited for the sky to change, but it never did. I was living in Springfield, Illinois, working as a journalist in one of my first jobs out of college. In my memory, the light was a perpetual February shade of dirty gray, and the temperature always just a few degrees above 40: too chilly to enjoy, not cold enough to snow.

This in-between place after college and before "real life" was a time of infinite loneliness and desperate boredom. Springfield wasn't where I had imagined I'd be at age 24. As an English major, I had entertained vague notions of myself living in Africa, like Martha, covering wars or wearing a pith helmet. But I had done nothing to further that dream, and student loans lay as heavy on my options as the prairie perma-cloud lay on my spirit.

I wasn't going anywhere exotic anytime soon.

Instead, I was adrift in a men's world, covering laws and committee hearings in the state capital. Every day I smoked a pack of cigarettes, drank six black coffees out of Styrofoam cups that I let get cold, and wrote two or three news stories before two in the afternoon. Then I went home to an apartment in a building that, in my memory, was a shade of brick that exactly matched the dull sky. I made myself food — I don't recall what, except that it was never pleasant or appetizing (I didn't yet know how to cook).

Trapped in my present, I followed her into her future.

Those were strange days. Doom hovered, even as I was struggling to conceive the person I was going to be. Chernobyl happened far away. One day, a squirrel fetus fell on me while I was lying in the thin spring sun.

I tried to focus on the person I wanted to be, but I was losing the wisp of a woman of great adventure and travel and dazzling love affairs, a woman who wrote it all down like the Greats. I looked in the mirror, and the girl staring back bore no resemblance to the Hemingway and Milton inside.

To keep my focus, I began some days with a morning swim at the Y and made regular visits to the library. Both were housed in buildings that were a shade of concrete that matched the sky.

And that's when I met Martha.

"Two elderly women sat knitting on that part of the veranda which was screened from the sun by a golden shower creeper" opens the first scene in the first book. A girl of 15 is nearby, sitting in "full sunshine" and reading a book. Once in a while, the girl "lifted her head to give them a glare of positive contempt."

The "glare of positive contempt." The book in hand. The sitting in full sun. I knew this girl.

Over the next months, I worked my way through the Martha Quest books. Reading about her was like listening to a chatty friend — a very, very smart chatty friend — recounting the stupid challenges and vagaries of female life. She understood my urge to give up. She knew that moods changed like the quality of light over the course of the day. She understood how yearning and revulsion, despair and manic hope, were always at war: "What was the use of thinking, of planning, if emotions one did not recognize at all worked their own way against you?"

When she transformed into the woman she was meant to become, she left me behind, too.

Martha's attitude toward pregnancy and motherhood was refreshingly and flagrantly disdainful. Like me, young Martha had a lot of sex and somehow didn't get pregnant. I believed in the inviolability of my body in that way, too. She was "quite comfortable in the conviction, luckily shared by so many women who have not been pregnant, that conception, like death, was something remarkable which could occur to other people but not to her."

Martha's attempts to change herself were not unlike mine. Like me, one day she decided to cut off her long hair herself. "Steadily, her teeth set to contain a prickling feverish haste" — yup — "she cut around her hair in a straight line." Then, Martha "plunged her head into water and soaped it hard rubbing it roughly dry afterwards, in a prayerful hope that these attentions might produce yet another transformation into a different person."

Trapped in my present, I followed her into her future. Martha falls pregnant and doesn't like it one bit. The quickening fetus is "the imprisoned thing moving in her flesh." She tries to get rid of it, guzzling an entire bottle of gin, "neat," glass by glass, takes a scalding hot bath to try to boil it out, and jumps off a table to try to "dislodge" it. A doctor tells her he could send to her a "factory" hospital where they will get rid of the four-month-old fetus. But his disapproval is clear. Martha cannot go through with it. Within the space of an hour, she goes from being certain of having an abortion to being elated by the notion that she is going to have a baby.

The thought of pregnancy and motherhood appalled me then. I was a nihilist, as far as the future of the planet was concerned, and would bring no baby into it at the expense of my own body. But I expected myself to survive for a while and do something great before the world ended. I just didn't know how I'd get there.

Exotic to me, South Africa was as dull as Springfield to Martha. Finally, she escaped, leaving husband, lovers, and children behind, and moved to London to become a writer. When she transformed into the woman she was meant to become, she left me behind, too. I tried, but I never could get interested in another of Doris Lessing's books.

Later, I would get around to my own transformations: from student to working woman, from reader of the greats to writer, from lonely girl to lover and mother. But, for a little while, a woman from 1930s Africa held my hand.

Bustle's "Without This Woman" is a series of essays honoring the women who change — and challenge — us every day.

Without This Woman, I Wouldn't Remember Your Name

Without This Woman, I Wouldn't Believe We Can Start A Revolution

Without This Woman, I Wouldn't Have A Closet Full Of Trophies (Or The Confidence To Win Them)