Wellness

Is Self-Care Making Us Lonely?

Welcome to the IDGAF era.

For Anna Pepe, alone time alone is nonnegotiable. It’s something the 24-year-old is vocal about on social media, where she has about 35,000 followers on Instagram and 121,000 on Twitter. On April 9, she tweeted, “distancing yourself from those who don’t value your time and energy is self care.”

“Self-care” can mean a lot of things these days. Pepe, a manifestation coach and hypnotherapist in Philadelphia, defines it as something that puts her in a good position to ensure she’s prepared for what the universe has for her. At the bare minimum, that usually requires a morning meditation, and sometimes she’ll take time for herself throughout the day too, perhaps in the form of another meditation or a walk without headphones.

“We need a phase in our lives, or maybe it’s a chapter, to focus on ourselves and ask deep questions, like ‘Who am I really?’ And ‘What do I want to do with my life?’ And that needs to be done alone,” Pepe tells Bustle over the phone. “Maybe it sounds harsh, but we need to set clear boundaries.”

In the wise words of TikTok, setting clear boundaries and focusing on ourselves means she’s in her IDGAF era, which the platform’s creators demonstrate as periods when personal needs and wants reign supreme. These can be simple, like not giving a f*ck while filming a dance or skin care routine, or more extreme, like ignoring calls — even if that action results in lost friendships.

The term “self-care” crossed over to the mainstream vernacular after the 2016 election and has been a trending topic — and a source of critique — ever since. Most people trace the use back to the late Black poet and activist Audre Lorde, who wrote in the late 1980s that “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” Lorde was talking about caring for oneself, particularly as a Black woman, in order to be able to have the energy to care for others and cope with racism, sexism, and the burden of fighting for justice. The term has since been commodified into something more akin to “wellness,” aka a nebulous term to treating oneself and feeling better. And, as anxiety and depression rates continue to increase, there’s a lot of money to be made in it; in 2021, McKinsey, the consulting firm, estimated the global wellness market to be worth $1.5 trillion and growing worldwide.

That “wellness market” of today often includes skin care products and salon treatments as part of its purview. “Sometimes [self-care means] going to the spa and taking baths and going to Lush and buying bath bombs or whatever,” Pepe confirms with a laugh. But she clearly balances those commercial tendencies (which, it’s worth noting, are solo activities) with cost-free practices, too.

This vision of self-care sounds different from Lorde’s. Her version was about taking time a little to yourself before you went back to battle with the outside world — a respite. This IDGAF era is more about a lifestyle of taking time for yourself to daydream, maintain inner focus, and relish time alone. But what if self-care isn’t just costing us money and making us selfish? What if it’s making us lonely too?

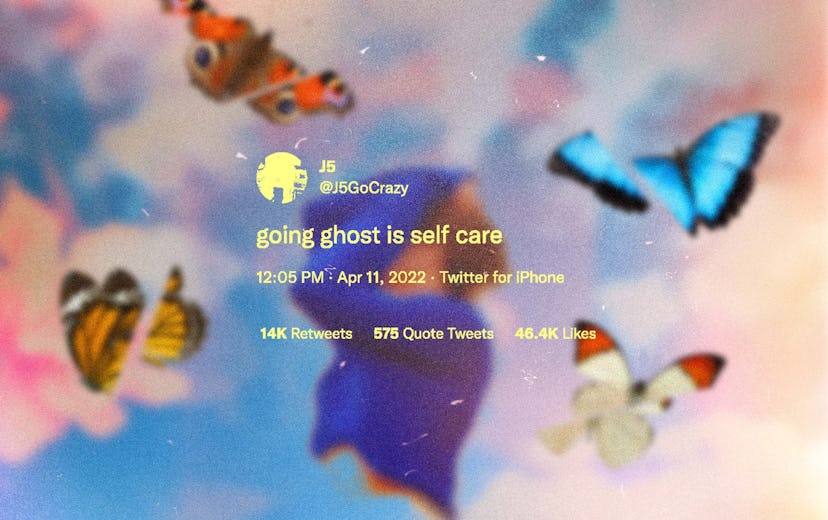

Last year, Harvard education researchers found that young adults (ages 18 to 25) were hit hardest by loneliness in the pandemic. They were in their prime adolescent or college years when COVID hit, a period that’s usually highly social, but instead spent that time in lockdown. To quote some viral tweets from earlier this year: “Being picky af about who you surround yourself with” (9.4K likes), “Limiting people’s access to your life” (33.3K), or “going ghost” (46.4K) may not be joyful expressions of downtime but possibly one of a generation of people for whom taking time alone has lost its negative connotations and become normalized.

So is this Generation Lonely? “I have encountered people in my practice who become deeply involved in healing and self-care in a way that becomes so engrossing they can’t live their lives,” says Whitney Goodman, a Florida-based LMFT and author of Toxic Positivity: Keeping It Real in a World Obsessed With Being Happy. “They often turn into a full time self-improvement project and have trouble just being. … Anything that forces you to isolate for long periods of time or to exclude important people from your life can become an issue.”

Age might be exacerbating the problem; or a reflection of the slightly selfish nature of those years. “In high school or college there is this groupthink going on where you have your little friend group,” says Pepe. “But there has to be a time to find yourself and ask what you want right now.”

It’s all a fine line, says Goodman. “People need time alone to heal or focus. Sometimes it’s necessary and other times it may be used as a form of protection or avoidance. That’s when it becomes problematic.”