News

CA Bans Grand Juries For Police Shootings

It's been more than a year since unarmed black teenager Michael Brown was slain by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson, a police killing that spurred months of outrage, protest, and vaulted the now-ubiquitous Black Lives Matter movement into the public consciousness. And now, the Golden State has taken a step towards rectifying a flaw in our criminal justice system, one which reared its head in the Ferguson proceedings — California has banned grand juries for police-involved killings, and that actually could end up being a very good thing.

The sad reality, as revealed by the non-indictment of NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo for the chokehold death of Eric Garner, is that grand juries really don't like bringing charges against members of law enforcement. For some perspective, as FiveThirtyEight detailed after the Wilson non-indictment, back in 2010 162,000 total cases were brought before grand juries in the United States, and a scant 11 of them resulted in non-indictments. When you consider the grand jury decisions over the deaths of Garner, Brown, and Ohio's John Crawford throughout the last year, this figure looks pretty stark — those three cases on their own would've amounted to more than 25 percent of all the non-indictments that occurred in 2010. Point being, grand juries often indict when cases are brought to them — but not in the cases of charges against law enforcement.

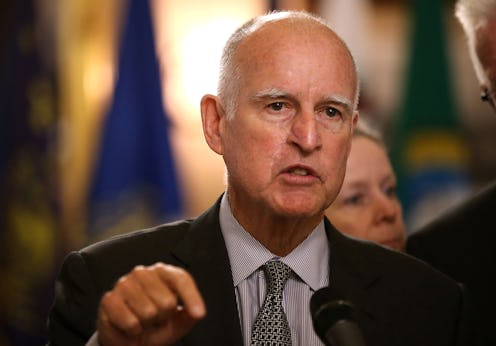

But, as perhaps best represented by the Garner case (thanks to the entire incident being captured by bystander on video), police tend to get a long leash as far as use of force goes. So California lawmaker Holly Mitchell, a Democratic state senator from Los Angeles, decided to author a bill taking police-involved killings out of the grand jury system altogether, and it was signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown on Tuesday.

So, what does this mean going forward? Mitchell's bill essentially strips the grand jury option from prosecutors, and puts the decision squarely in their hands — basically, it'll be the prosecutor's call whether or not to bring charges. Mitchell explained her rationale in a statement on Tuesday.

One doesn’t have to be a lawyer to understand why SB 227 makes sense. The use of the criminal grand jury process, and the refusal to indict as occurred in Ferguson and other communities of color, has fostered an atmosphere of suspicion that threatens to compromise our justice system.

Of course, it's not as though turning everything over to the prosecutors themselves is a foolproof solution. Owing to the typically close nature of professional relationships between prosecutors and law enforcement, shifting the responsibility to them could nonetheless result in a continuing pattern of non-indictments of officers.

After all, St. Louis prosecutor Bob McCulloch's extremely bizarre handling of the Darren Wilson grand jury — after which he admitted some witnesses had "clearly" lied to the jurors, but defended presenting their testimony because "it was much more important to present anybody and everybody" — is a testament to the distrust so many people feel towards every aspect of the justice system, at least when a cop is involved.

The decision does change the stakes relating to public pressure, however, and that could change things considerably. For example, the extremely abnormal, deferential, downright weak way the grand jury process treated Wilson led some observers to theorize that the state didn't actually want to prosecute Wilson, and may have called the grand jury to appease public outcry. Now, there's no grand jury safety net for the prosecutor — they have to either let the officer off entirely and absorb the outrage, or bring criminal charges and settle in for an actual trial.

Simply put, whether it alleviates the problem or not, the process of justice in police-involved killings in California will be worlds different than it was before. The law won't be implemented immediately, however — according to Colorlines, it won't take effect until January 2016.