News

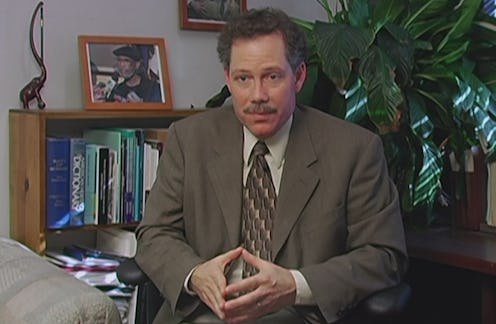

Steven Avery's Ex-Attorney Talks Forensic Science

Netflix's true crime documentary series Making a Murderer first debuted in December, and it's generated a boom of information and interest. Telling the tale of Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, man Steven Avery, who was wrongfully convicted in 1985 and exonerated in 2003, only to be again tried and convicted of murder in 2006, the series has brought issues of evidence, guilt, and reasonable doubt to the forefront, and on Friday, one more person added their voice: Steven Avery's ex-attorney Keith Findley discussed forensic science and the scourge of wrongful convictions in an interview with Colleen Henry of WISN, Milwaukee's ABC affiliate.

I know what you're thinking ― "wait, which lawyer is he?" He's not Dean Strang or Jerry Buting, the two attorneys who were hired to defend Avery after he was charged with murdering Teresa Halbach in 2006. Rather, it's Keith Findlay, who is featured in the very first episode of the series. It details Avery's wrongful 1985 rape conviction and his eventual release from prison in 2003. Findley was the lawyer who helped secure that exoneration, working with the Wisconsin Innocence Project.

The video of Findley's interview is exclusive to WISN, so if you'd like to hear him tell it himself, you should check it out. He didn't address Avery's role in the case, or whether he was innocent or guilty ― according to Henry, he didn't do so since he no longer represents Avery, and his current case is ongoing ― but he did touch on the role that forensic science can play in wrongful convictions.

Specifically, he denied that there's anything "flawless" or "sexy" about it, and explained that sometimes the general public has a mistaken impression about just how much it can tell you:

We're fascinated by science, we've got all these CSI shows that make everybody believe that the science is instantaneous, flawless and sexy, and it's none of those. ... The science isn't there to allow us to say that this shoe print, or this bite mark came from this person and no other person.

The big exception to this is DNA evidence, which is undoubtedly the strongest and most informative type of forensic evidence an investigation can turn up. It can, however, be falsified. While the state's murder case against Avery did include pieces of DNA evidence ― on Halbach's car key, on the hood latch of her car, and inside her car in the form of his blood ― his defense team argued that the evidence could have been planted by the police. Whether it was or wasn't may be impossible to know at this juncture, to be clear, but DNA evidence can theoretically be planted like any other kind.

In fact, when Avery's defense team argued that his blood had been planted from a vial stored by the country from his previous conviction, that set in motion the FBI testimony that Findley would describe to Henry as "really problematic." If you've seen the series, you'll probably remember this too: the EDTA test.

In an effort to rebuke the defense's argument, the prosecution called Dr. Mark LeBeau of the FBI to testify that no EDTA, a preservative used in such blood vials, had been found in the blood from Halbach's car. This helped convince the jury that it hadn't been planted, but suffice it to say, Findley had some issues with that, too, especially the fact that LeBeau testified that he knew the case involved an allegation of planted evidence before he conducted the test. As he told Henry:

He doesn't need to know why he's doing the testing. If it's a valid test, he should be doing it blind. Whether the outcome was right or not, the process of developing an presenting this scientific evidence was really problematic.

It's interesting to hear some of Findley's perspective on things, since we've already heard so much from the other major legal players in the case ― primarily Strang, Buting, oft-criticized former public defender Len Kachinsky, and former Calumet County DA Ken Kratz for the prosecution. Avery is now represented by Chicago-based lawyer Kathleen Zellner.

Images: Making a Murderer/Netflix; WISN