If you open up a magazine nowadays and take a look what's going on in men's style, you might notice a parade of sheer chiffon shirts, bell-sleeves, pastel hues, and sassy berets. Gender lines are blurring, but it's not for the first time. The Peacock Revolution of the '60s and '70s pushed against gender roles and gender presentation much in the same way that fashion houses like Gucci and Prada are doing now. By arming men with chiffon and silk, effeminate silhouettes and flamboyant prints, facets of the sartorial world have long been helping broaden the definitions of "masculinity" and "femininity."

But let's take things back 50 years and pinpoint where it all began. Before the likes of Jimi Hendrix and his brocade jackets and Mick Jagger and his crop tops, the Western world experienced the bowler hat brigade: Masculine businessmen who, for the most part, subscribed to the "tough guy" mentality. By and large, they left all the "self-expression" frivolity to the women at home.

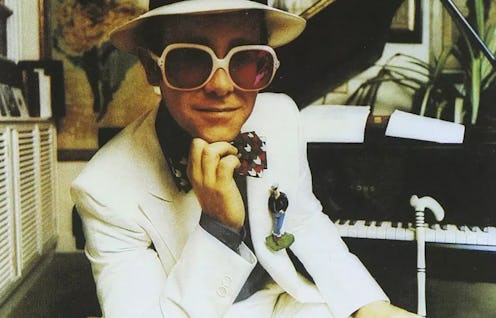

With the ushering of the Peacock Revolution, however, fashion opened up an exciting pluralism for the newly created male Dandy; one where he could dabble in androgyny while simultaneously expanding what it meant to be masculine — or even better, getting rid of gender binary restrictions altogether. Men and those assigned male at birth could rock "women's" clothes and women could wear "men's" clothes, challenging gender rules along the way. So below are seven ways the peacock revolution was important for gender norms.

1. It Let A Generation Explore Individuality

In the 1950s, men's fashion was, for the most part, as cookie cutter as the neatly-trimmed lawns in Suburbia USA. Gender norms stated that men were supposed to be the bread-winners and totally business minded — creativity and self-expression were traits earmarked for the ladies. But that all changed with the post-World War II Baby Boom generation — the youthquakers who snapped up the Peacock Revolution in order to have a chance to express themselves outside of a work week uniform.

According to Berg Fashion Library, "These 'youthquake' men grew their hair long and donned radical new styles of clothes largely as a break with the conformist traditionalism of their parents, but also as a way to explore and assert their individuality."

In the span of a decade, men's fashion went from baggy brown suits to Swinging London dandy. Berg Fashion Library painted a picture, reporting, "Among the diverse new options in menswear were vividly colored and patterned mod fashions from Carnaby Street in London. From Paris, couturiers expanded their fashion creativity to include menswear, offering innovative suit designs with shaped, youthful silhouettes and iconoclastic details like collarless necklines."

No longer did a man have to look like a mannequin. He could choose new cuts, fabrics, and silhouettes to best express his personality. And it didn't stop there. "In America, street looks from college campuses and music festivals ranged from subtle antiwar protest styles such as flower power motifs to homemade hippie styles like tie-dyed T-shirts and jeans." In addition to that, Arabian caftans, African dashikis, and silk kimonos were also viable options that could now end up in a dude's closet.

With these fresh new options, men were allowed to dabble in self-expression. As Michael Fish, the owner of boutique Mr. Fish (a '60s fashion label that helped usher in the Peacock Revolution), told Newsweek, “Clothes should not reflect how ‘they’ or ‘I’ think you should look. [They] should reflect how you want to look.”

2. It Broadened The Definition Of Masculinity

Just a few years prior, ironed slacks and fedoras were the name of the game, so stepping outside on a normal Wednesday afternoon wearing sweater suits, Mary Jane's, and chinchilla coats might have seemed a little scandalizing. But through the Peacock Revolution, some men were able to blur the gender lines without that much push-back. Why? Because all the hottest rock stars were doing it, too. And if sex bombs like Mick Jagger were stepping on stage in dresses and Jimi Hendrix was rocking poet blouses, then one's masculinity was obviously not something to be threatened because of clothing.

For example, in a 1969 article from the Eugene Register-Guard, a fashion writer reported, “The Beatles charged, first through Europe and then this country, and the gleeful young followed them into Prince Valiant hairdos, suits buttoned to the chin, and flamboyant haberdashery." If The Beatles could pull off paisley shirts and rock-candy colored suits — dabbling in femininity without being considered effeminate — then the men listening to their records at home could, too.

The Guardian pointed out, "Ever since Elvis wore eyeliner, men in rock have enjoyed a bit of dressing up and challenging the cultural idea of masculinity. Some of the most iconic men in pop — David Bowie, Marc Bolan, Jimi Hendrix — ruled rock’s airwaves done up to the nines in frilled blouses, glitter makeup, brocade, high heels, and feather boas."

These looks weren't feminine, per se. Instead, they broadened the scope of what it meant to be masculine. They were subversive and rule-breaking, which only added to the draw.

3. Gender-Specific Clothes Became Square

Before the '60s, dresses and chiffon frills were details that could only be found inside women's department stores. But after World War II, boundaries were nudged and one could find the same mod designs in the closets of all genders.

The L.A. FIDM Museum — a museum devoted to the exhibition of dress and textiles — explained, "All aspects of menswear were under assault: Neckties were replaced by scarves and ascots, turtlenecks became an alternative to the button-down shirt, multi-colored shoes and sandals replaced black Oxfords, and hair grew longer. Color and pattern appeared in menswear, as did traditionally 'feminine' fabrics such as velvet, satin, and chiffon."

Clothing became increasingly androgynous as many women and men shopped at the same boutiques for the same outfits. FIDM reported, "Gender specificity was no barrier [...] for in 1968, WWD reported that men were purchasing women's wide-legged pants for their own use at the Yves St. Laurent boutique in St. Tropez."

Why was this important? Because it allowed gender to become non-binary. With men allowed and encouraged to wear elaborate and stereotypical-female looks, the restrictions of what it meant to be "masculine" were also loosened. With the ushering of flamboyant high heels and Tommy Nutter suits, gender lines blurred just a little bit more.

4. It Helped Normalize "Queer" Fashion

While donning feather boas and beaded velvet jackets might have felt progressive for the newly-labeled London Dandies, many gay men have been wearing them for years. But with the decriminalization of homosexuality in Britain circa 1967, several stereotypically "queer" looks caught the attention of the general public and went slightly more mainstream.

According to Toija Cinque, Christopher Moore, and Sean Redmond, authors of Enchanting David Bowie: Space/Time/Body/Memory, "The change in men's dress from drab to debonair in London in the '60s during the Peacock Revolution constituted the effect the adoption of gay men's dress style by the non-gay, male population." During the youthquake era, the aggressive need to defend heterosexuality dwindled away more than it ever had before, and so the adaptation of queer style didn't seem as taboo as it would have in the past.

Wearing slim-fitting trousers, brocade jackets, and chiffon blouses captured “the spirit of gay sartorial style emerging from the shadows boldly into the public arena."

According to The Guardian, when David Bowie donned a silk dress for his Man Who Sold The World album cover in 1970, Rolling Stone magazine described it as “ravishing... disconcertingly reminiscent of Lauren Bacall." When such a blatant display of gender-bending is met with such positive reviews, then you know you're headed in the right direction.

5. It Let Men Rebel Against Gender Expectations

While many women were busy burning their bras and rejecting putting on lipstick for the patriarchy, the Peacock Revolution allowed more men to reject those same kinds of gender-based restrictions. The FIDM Museum explained that the debonair way of dressing was "conceived as a sort of costume which allowed one to try out or take on a new identity at will. The rejection of the staid business suit freed men from societal expectations regarding personal identity and allowed for a truer expression of the self."

Back in the day, most Western men were expected to maintain a Lyndon B. Johnson-esque air to their aesthetics — all baggy, sober suits that hinted of responsibility, bread-winning, and a hard head for negotiation. In other words, all stereotypically "masculine" traits. But shrugging on a crushed velvet blazer in ruby red allowed the wearer to reject those limitations and broaden the scope of their unique masculinity.

Men's newspaper Eugene Register-Guard explained, “[The new man] wore jewelry, furs, buckles on his shoes, wildly printed shirts and ties (if ties at all) — all in a flambouyant rebellion against the Wall Street Uniform.” Lots of men wanted to eschew the idea of the "Madison Man" or the "Suburban Family Man," and instead be allowed to explore other personas that might set them apart from their gender. Their clothes allowed them to do just that.

6. It Reached The Elders

When you think of radical new trends and progressive ways of thought, you might conjure up imagery of youthfulness. It's those crazy teenagers and 20-somethings who are cross-dressing in each other's closets and pushing the envelope on what it means to be a man. Right?

Well, not always. The Eugene Register-Guard explained, “Bill Blass introduced his 'gangster' suits for bankers. The collarless Nehru jacket appeared on Wall Streeters as well as the Third Avenue bar set. If the dinner jacket wasn't Nehru, then it was velvet — black, brown, and even red. The jacket was so skinny that Mark Cross introduced handbags for men to carry their gear in.”

So why did the older crowd adopt the peacock-ed aesthetics? According to the Eugene Register-Guard, "10 years ago, the average male remained safely hidden behind the drab anonymity of his uniform, a dark three-button single breasted suit. Today, men are unafraid of criticism which would have deterred them 10 years ago from showing originality in their wardrobes.” The post-war world fostered a new sense of open-mindedness, allowing even those who were traditionally "masculine" to negotiate the terms a little.

7. It Introduced Androgyny To Future Decades

With just as many businessmen as glam rockers seemingly wearing skinny suits, the Peacock Revolution started a domino effect for androgynous fashion that continues to the present day. In the '80s, we saw rockers decked out in hairspray-and-tan looks, while in the '90s the likes of Kurt Cobain performed in prom dresses and tiaras. The Guardian explained the progression perfectly, citing, "It runs from Little Richard and his eyeliner to the Stones and Jagger’s dresses, Prince’s pants-plus-stockings Dirty Mind look, Manic Street Preacher Richey Edwards’ fur coats, Kurt Cobain’s tea dresses, and the blouses that Suede’s Brett Anderson and Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker picked up in the women’s section of their local charity shops."

While our grandfathers from the '70s started the conversation with their ascots and bead work, the following decades refined the debate. When a hetero man embraces effeminacy, he presents the idea that self-expression needn't have anything to do with gender. Masculinity doesn't have to be questioned or defended, and gender presentations don't have to box in those who aren't willing to be packaged away into their cookie-cutter suits or dresses.

The Atlantic explained, "Using clothes to play with gender in this way isn’t just about looking pretty: It’s highlighting the edges of society, celebrating outsiders and questioning norms."

Nearly 50 years after the Peacock Revolution, we're still questioning. Here's to never allowing the skepticism to stop.

Images: Thema Music (1); The Face (1); Mercury Records (1); Polydor (1); Capitol Records (1); Mirage Music (1)