With award-winning photographer Substantia Jones of The Adipositivity Project, Bustle is launching A Body Project. A Body Project aims to shed light on the reality that "body positivity" is not a button that, once pressed, will free an individual from the horrors of beauty standards. Even the most confident of humans has at least one body part that they struggle with. By bringing together self-identified body positive advocates, all of whom have experienced marginalization for their weight, race, gender identity, ability, sexuality, or otherwise, we hope to remind folks that it's OK to not feel confident 100 percent of the time, about 100 percent of your body. But that's no reason to stop trying.

At times, watching Justin Robert Thomas Smith move through the world feels a little painful. Not painful in the way a Charlie horse might hurt after you've been sitting cross-legged on a hard floor for an hour; but rather, painful in the kind of way seeing something delicate in a very non-delicate surrounding would be.

Smith is soft in a way so much of the world isn't: He's compassionate; incredibly intelligent. He's a dancer, a writer, an artist, a philosopher, and a self-described "catalyst for change." As a gay man of color living in an American social climate that still largely vilifies LGBTQ individuals and POC simply for existing in the sexualities and bodies they inhabit, one might assume he'd be somewhat hardened. On the contrary, Smith is anything but.

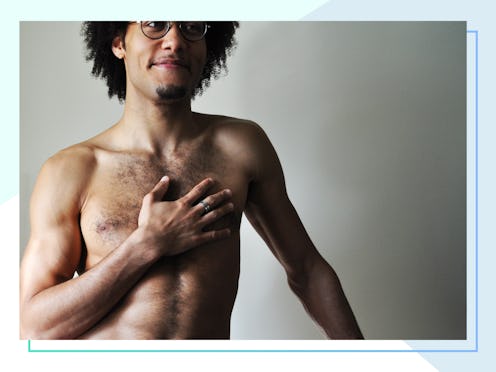

After he disrobes to shoot with Substantia Jones, he comes out of the bathroom wearing baby pink swim shorts, and there's a timidity to him that I've rarely seen in the 10+ years I've known him. "As someone who is more typically behind the lens and is also very picky when it comes to how I like my body to be framed — partially due to artistic preferences, though I'm sure there's some underlying body hang-ups guiding those preferences — letting go of that control and allowing another photographer free reign on my body was for me perhaps less empowering and more so exciting," he tells me later. "Though in a subtly frightening way."

Smith and I were both raised in the same conservative South Jersey town: One where being anything non-thin, non-white, non-straight, non-spray-tanned or Billabong-wearing meant you were likely to be outcasted by many peers. It has been through dance that Smith has grown further "strongly about breaking the stigma" against aesthetic and body-related shame.

"I think that having trained as a dancer has really made me acutely aware of the impact that not coming to terms with your own body can have on — well, everything you do, and on how you allow yourself to move," he says. In order to dance fluidly, effortlessly, one arguably needs to be very in control of the body. If too absorbed in moving cautiously due to anxieties over said body, those anxieties will translate to the audience. Although Smith makes this observation in relation to his own dance practices, exercising control and autonomy over one's physical form is undeniably crucial for most folks: A means, perhaps, of demonstrating self-love externally even when it's not 100 percent present internally.

In conversations with Smith, it's always been evident that he understands that his experiences as a thin man automatically set him apart from those more marginalized for characteristics such as weight or gender identity. But perhaps as a byproduct of being a dancer (while precise statistics have yet to be calculated, extreme body image issues and eating disorders are thought to be incredibly common in dance), or simply of living in a culture that conditions most of its inhabitants to never-feel-quite-good-enough, there is still one body part that he has still struggled with throughout the past quarter of a century: His chest.

"Though minor weight gain over the last couple years has filled in some parts of my otherwise rather bone-y body, my chest remains a constant eye sore when I look in the mirror," he shares. "I've done some research on it, and it would seem that I was born with a very minor form of pectus excavatum [whereby a 'person's breastbone is sunken into his or her chest,' as per the Mayo Clinic], often called 'funnel chest.' Because of it, my rather lanky form, and the fact that my rib cage is rather large for my body size, I have also developed an arched back, causing my chest to become more pronounced."

Although few would likely notice that there are any peculiarities to Smith's chest, the reality of body image hang-ups is that they are often inexplicable — housing no rhyme or reason, per se, but saying quite a lot about the culture of self-critique they were born in. For Smith, an unlikely tool has served as his most favored source for body love: the mirror.

"Engaging with my body on a daily basis... having the internal conversations that I need to be having, and coming to terms with what my body is and what it can be: This is what the mirror helps me to do."

It's not an admission of vanity, but of reflection. The mirror is often a manifestation of body dysmorphia: Of insecurities we are not yet ready to face or tackle. But what if we forced ourselves into its gaze a little more? What if, instead of avoiding the mirror based on everything we feel it represents, we could assign it another narrative entirely?

"I cannot say that the struggle is over for myself, but I do think that self-communication is, above all else, a necessary step in overcoming body negativity," Smith muses. "The voice inside our heads that continuously tells us that we don't look good, that we can't wear that because of this or that reason — that voice, you can talk to that voice. With that voice. You can have a mature conversation with that voice and you can make that voice understand that if there is to be any critique made on your body, it must be made constructively."

To converse with the mirror — the thing that we might often feel has nothing to spew but negativity — might feel like a foreign concept. A difficult concept. But cultivating self-love in the current state of beauty standards is never easy. It's often coming face to face with our bodies, however, that aids us on our journeys the most.

When reflecting on the shoot with Substantia, for instance, Smith tells me, "Freeing my body up for the camera and allowing even the more uncomfortable body parts some airtime seemed a requirement if I was to be true to that premise [of body positivism]." He adds that photography, in general, is not to be underrated when it comes to feeling at one with your physical form. "Portraits of your face and body allow yourself time to digest what you're seeing — to have the conversations you need to have with yourself... to really pinpoint your 'problem areas' and ask yourself, 'Well, what's actually the 'problem?'"

More often than not, there isn't any tangible, real problem. There isn't anything "bad" or "disgusting" or "unappealing." There's just a body: A body with quirks and idiosyncrasies, perhaps. But for those same reasons, a body that's ultimately much like any other.

When asked how he feels about his chest now, Smith tells me, "Well, I woke up at 2 p.m. today and it's now 4:30 p.m. and I've not moved outside of a three-foot radius from my bed, so I guess I have bigger problems to deal with at the moment. ~Shrugs.~" It might seem flippant — easy for him to say as a thin man, and perhaps in some respects it is. But the sentiment is one that might translate to those across a myriad of body types. There are always more valuable things — things more worthy of emotional investment, energy, and time — than preoccupying oneself with someone else's beauty standards.

Images: Substantia Jones/Bustle (5)

With Editorial Oversight By Kara McGrath and Marie Southard Ospina