With award-winning photographer Substantia Jones of The Adipositivity Project, Bustle is launching A Body Project. A Body Project aims to shed light on the reality that "body positivity" is not a button that, once pressed, will free an individual from being influenced or judged by toxic societal beauty standards. Even the most confident of humans has at least one body part that they struggle with. By bringing together self-identified body positive advocates, all of whom have experienced marginalization for their weight, race, gender identity, ability, sexuality, or otherwise, we hope to remind folks that it's OK to not feel confident 100 percent of the time, about 100 percent of your body. But that's no reason to stop trying.

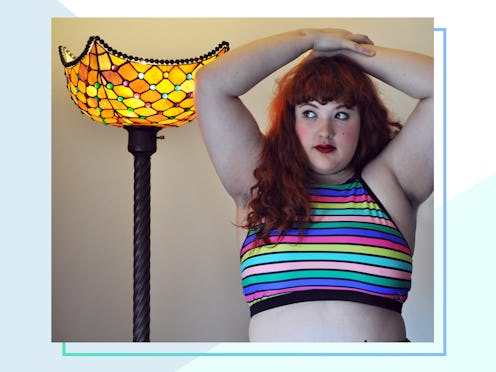

Marie Southard Ospina is not feeling her best. A mysterious allergic reaction made her face swell with an angry, red rash over the weekend, and it has persisted all the way to our Thursday photo shoot with Substantia Jones. She’s hesitant to take Benadryl, in case it makes her too drowsy to happily pose for the camera in her bathing suit, but after layering makeup over her breakout proves too painful, she gives in. After popping a little pink pill, applying some lightweight foundation, and throwing on her striped bikini, Ospina jumps in front of the camera with a smile. As a writer and body positive activist, she’s made a living out of ensuring marginalized voices have a platform from which to share their often silenced views, and she certainly isn’t going to let a little redness stop her.

The hidden rash in these photos feels like a perfect metaphor for Ospina’s overall relationship with her body. In the two plus years we've worked together, she’s taught me all about the body positivity movement, setting an example in the office by wearing brightly colored crop tops and short shorts generally deemed fashion “don’ts” for plus size humans. Her articles and social media posts are flooded with commenters saying they wish they had her confidence and thanking her for being such a source of inspiration. It’s hard to believe that she was ever unhappy with her body. It’s even harder to believe that she’s still trying to be entirely in love with every part of it. Her arms, in particular, can make Ospina hesitate in front the mirror these days, convincing herself they're worthy of being shown off in a tank top or off-the-shoulder dress. But they weren't always the part she struggled with most.

Ospina was raised by her Colombian mother, but inherited a lot of her “very big and broad" father’s European body features. While she tells me later that she “can’t blame my mom for all my body image issues,” Ospina does believe that the super specific Columbian standard of beauty (a big butt, big thighs, and flat stomach) her family encouraged, combined with the American obsession with thinness, played a part in her poor body image and eating disorders growing up. “If I was ever going to have the Colombian big butt and big thighs, I was also going to have a big belly,” she tells me. And that confused the adults in her life, who would make comments about her looking pregnant and needing to “do something about it.”

Back then, her arms were barely a second thought — it was her round tummy that she believed she most urgently had to fix. “If I sat down to go to the bathroom in high school and noticed that [my stomach] was hanging over my legs… that was it,” Ospina says. “I was just a devastated mess for a day, that was less calories eaten that day.”

It wouldn’t be until her junior year of college that Ospina would begin to realize her plus-sized body was not an inherently bad thing. She studied abroad in Spain and the Czech Republic, both places which, as far as Ospina could tell, had a much more flexible definition of who was beautiful. When a friend from from Madrid asked Ospina whether she wore boxy, loose-fitting clothes because she liked them or because she was trying to hide something, Ospina realized she’d been limiting herself based on arbitrary rules about what fat individuals can and can’t wear.

“[Studying abroad] was the first time I saw fat women wearing bodycon dresses and miniskirts, in Spain especially,” she says. “Seeing people who I could relate to wearing things that I had always liked, but never felt like I could because of my size — it was really great.” Ospina thought these women were beautiful, which started to help her see her own, similarly-shaped body as equally worthy of love.

When she got back to America, Ospina started seeking out and reading plus size bloggers like Gabi Gregg and Nicolette Mason. She read radical body positive literature by authors like Virgie Tovar and Marilyn Wann. She started looking a photographers like Substantia Jones who celebrated fat and other marginalized bodies. When she was assigned to create a blog for a journalism class, it seemed natural that she would start a blog about body positive activism, and so Migg Mag was born.

As this was happening to Ospina, the mainstream was starting to catch on to this whole body positivity thing — at least the very basic idea that "all bodies are good bodies." Brands started putting plus size models in their advertisements. Magazines started using more “real women” in their fashion spreads, and shied away from phrasing that implied anyone with a round tummy couldn’t partake in the crop top trend.

All this is technically progress but, as many activists have noted, the models in these new, allegedly body positive ads and fashion spreads still looked a lot like the models we’ve been seeing for decades — just scaled up a bit. They were still mostly white, rarely above a size 12, and definitely always had flat stomachs, big boobs, and a thick butt. So while the media was claiming that all bodies were defintiely good bodies, the people the movement was originally started for — bodies of color, differently abled bodies, trans bodies, and other marginalized bodies — still weren't (and for the most part still aren't) getting the visibility they were fighting for.

Until recently, Ospina says she was, for the most part, this type of “good fatty” that was suddenly being lauded in ads. She tells me, “I’ve always had ‘hourglass privilege.'” According to society, this is the most feminine of all the body shapes, and Ospina says she’s always identified positively with feeling traditionally feminine. She’s drawn to vintage inspired clothes with cuts that emphasize her curves. She loves bright lipsticks and rosy blush.

But about a year ago, her health insurance stopped covering the birth control she was on, so she decided to give her body a break from the hormones rather than find an alternative. But Ospina has polycystic ovarian syndrome, and when she went off the birth control, her symptoms started resurfacing. PCOS elevates your testosterone levels, which, for Ospina, meant she was suddenly hairier and broader in the chest and shoulders than she had become accustomed to. To her, it felt like that curvy hourglass body she’d come to love had changed entirely.

Suddenly, she found herself going through another body positive journey, this time trying to feel affection for her newly broader arms. “I really had to question my own body positivity and kind of identify whether I’d really come a long way or whether I’d only really come a long way because I was still operating under a different set of beauty standards,” Ospina says.

As a relatively well-known fat positive, female writer on the internet, Ospina deals with criticism and insults from every variety of trolls you could imagine on a daily basis. But she’s mostly over them by now. (“Actively choosing not to care is the first step [to not letting trolls bother you],” she says. “Just tell yourself ‘I’m not gonna care’ until it’s true.”) She’s also made it a point to disassociate with any negativity in real life too, cutting ties with friends who frequently made body negative comments and telling her mother she was “putting a ban on body talk” when they’re together.

All this means that now Ospina just has to come to terms with herself — something that is arguably the hardest part for any of us attempting to complete our body positive journey. So, with a less extreme starting point, she’s backtracking to the beginning of the body positive journey she began in junior year of college when she discovered all those fat women wearing whatever the hell they wanted. The most important step is one she recommends for anyone having a rough time loving themselves: Change what your newsfeed looks like.

Once she realized she was feeling crummy about the way her arms and shoulders looked, Ospina "started seeking out boxy fats,” a term for women who don't have that hourglass shape. “I really don’t think we should underestimate the power of changing our newsfeed when we are struggling with anything,” Ospina continues. “Changing our media intake and catering the images that we’re consuming to what we need psychologically at any given moment.”

But finding those sources of alternative inspiration can be hard, especially now that the once radical #bodypositivity hashtag on Twitter and Instagram can feel flooded by traditionally attractive individuals. Ospina is always quick to clarify that straight sized, white humans deserve to love their bodies too, but this new iteration of a movement that was once about making marginalized bodies feel like they were worthy means people who are plus size, queer, disabled, or not-white need to look elsewhere for that feeling of inclusion and inspiration. For non-hourglass fat people in particular, Ospina recommends #celebratemysize, #alternativecurves, #fatpositivity, and #fatacceptance instead. Ospina has found that following other people who look like her and are completely in love with their bodies can help her realize her similarly shaped body is worthy too.

But, while scrolling through your Instagram feed from bed is one thing, going out into the world flaunting the body part you’re struggling with is something else entirely. On days when Ospina is feeling particularly meh about her arms, she makes herself wear something that shows them off. “I will force myself to wear a spaghetti strap or strapless outfit,” she says. “That forces me to look at that body part throughout the day, in the mirror in the bathroom, and just normalizes it a little bit more for me.”

If that sounds (understandably) scary, Ospina recommends warming up by wearing the outfit around your house first. A lot of self love activists suggest spending time with your nude body, which is something Ospina encourages as well, but also says that wearing outfits you might actually rock in public can be even more helpful. “If you start conditioning yourself to wear the things that might be the scariest because they’ll have the body part on display the most, it does help once you’re at that point where you actually have to wear that thing in public where people are gonna see you,” she says. And take selfies while you do — Ospina tells me seeing yourself in a bunch of photos from a bunch of different angles can make your realize how good you actually look in a way a mirror never could.

Ultimately, no matter how many fat positive people you follow on Instagram or how many hours you spend running around your house in a low rise bikini, Ospina emphasizes that nothing is instant. That you may spend years thinking you’re 100 percent body positive, only to wake up one morning feeling crummy your stomach or your arms or your boobs or your genitals. And that’s OK.

Even if Ospina still has days when she wants to cover up her arms with a sweater, she’s optimistic about loving them completely in the very near future. “I certainly love my body infinitely more than I did before I was introduced to fat positivity and body positivity,” she says. “I can’t even quantify it because it’s such a huge, drastic difference. I think that says a lot for the power of crafting an alternative narrative.”