Imagine straightening your skirt at a swanky bar and, glancing down, you take in the thick, month-long stubble on your legs. A kind of dark fuzz that doesn't trigger any panic or make you want to shift your yeti shins away from the light. That kind of reality would be shocking, right? The history of shaving made sure it would be, where your body hair weirds out the people around you and makes you feel uncomfortable for no understood reason. After all, it is just hair. Why would hairy patches around your knees be any different than your eyelashes or the fuzz on your arms?

Still, hair in certain places takes on a completely different meaning when it comes to women, and we could thank the beauty industry for that. They practically forced a pink razor into our hands during the turn of the 20th century, urging modern women that bobbed their hair and thought themselves metropolitan that this was the new normal. During a time where just the term "underarm" would call for smelling salts, splashing smooth pits across magazines and encouraging women to worry about them was a huge turning point. But was it for fashion? Was it for the pleasure of primping and playing at a vanity mirror? The way history tells it, it was all about dollar signs. Below is the sneaky history of shaving, and how the beauty industry played the long con when it came to the woman's razor.

How The First Women's Razor Came Into Play

King Camp Gillette was the man behind the lady razor and the one to thank for adding an extra 15 minutes to our shower time. Prior to 1915, body hair on a woman was seen as a non-issue thanks to the straight-laced styles of the Victorian era — with women draped and buttoned up to the chin, shaving your armpits was as odd and unnecessary as shaving off your eyebrows. But when Gillette realized he could double his profits by doubling his customers and introducing women as shoppers, he got to working on how to bring blades into powder rooms. "Gillette was very canny about increasing consumption of his products, and targeting women was one part of that strategy," Rebecca M. Herzig, author of Plucked: A History of Hair Removal , shares in an email interview with Bustle.

Luckily for him, the changing times allowed him to slide that idea right in. In the early 1900s, women were loosening their chignons and leaving the stuffy Victorian ideals of their mothers' behind. No longer would they be wearing ground-dragging dresses and stiff petticoats — as the feminine ideal changed to something a little more freer and bohemian, so did the fashion. Enter the garconne dresses and boxy shifts that raised hemlines and nipped away sleeves. And with all that extra body being on display, Gillette found his opening.

How Advertisers Helped Convince Women Of Their Faux Pas

In 1915 Gillette created the Milady Décolleté razor, and to put it on women's radars he advertised it as an accessory that was as necessary to buy with a modern dress as a hat or pair of gloves. "Small and curved to better fit the armpit, the razor was designed to supplement the sleeveless and sheer sleeved fashions of the period," Hertzig confirms. To convince women that buying a razor came part and parcel with buying the latest fashion, catalogs began to cleverly market the two products together. For example, anti-underarm hair ads were appearing "in McCall's magazine by 1917, and women's razors and depilatories showed up in the Sears, Roebuck catalog in 1922, the same year that company began offering dresses with sheer sleeves," Anita Renfroe, author of Don't Say I Didn't Warn You, explained in her book.

The first advert that ran for the women's razor was a one-inch square in Harpers Bazaar , and with that small bit of ad real estate new rules for femininity were drafted. Shaving wasn't going to be a passing trend but a new part of what it meant to be a proper woman in polite society.

After all, the goal of advertisers and magazine editors wasn't to meet women’s needs — it was to create new ones. That was the only way to keep products moving off of shelves. And with more problems women had to worry over, the more magazine issues an editor was able to sell. For example, Cyrus Curtis — the owner of Ladies' Home Journal — shared in a speech to advertisers, "Do you know why we publish the Ladies’ Home Journal? The editor thinks it is for the benefit of American women. That is an illusion…the real reason, the publisher’s reason, is to give you people who manufacture things that American women want and buy a chance to tell them about your products," Joan Jacobs Brumberg shared in her book, The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls. Magazines were just ads gift wrapped in advice to get women to buy them and their products. And buy them they did.

How Wording Made A Difference

The key in making women buy the product was to make shaving a new but unmistakable part of womanhood. Gillette knew that, and so he and his publishers used polarizing words in their ads, drawing a hard line between what it meant to be a man and a woman. "As the first company to introduce the concept of shaving to women, Gillette was cautious not to be too modern. In their early advertisements for women, Gillette did not to use the word 'shaving' but the word 'smoothing' instead. 'Shaving' was an activity men engaged in; 'smoothing' was more feminine," Kirsten Hansen, a graduate of women’s liberal arts school Barnard College, explained in her senior thesis. "Very few Gillette ads for women used words like 'shave' or 'razor' or 'blade' at all. The cultural association between men and blades was so deep and so old that they had to worry about making their products seem 'feminine' enough," Herzig confirms.

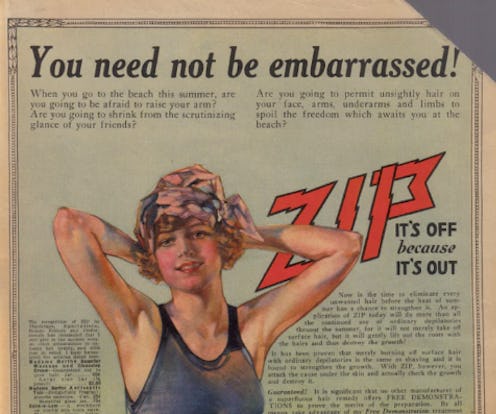

Companies also picked out language carefully, creating a story where body hair had negative connotations and would dock points from a woman's scorecard. For example, X Bazin, a shaving powder brand, shared that their product was used by "women of refinement" for generations to remove "objectionable" hair. Gillette labeled body hair "an embarrassing personal problem" and smooth underarms a "feature of good dressing and good grooming," while another ad claimed you'd be "unloved" and "embarrassed" if you had "ugly, noticeable, and unwanted hair." If you shaved you were dainty, attractive, and stylish. If you didn't, you risked being pegged as the opposite.

The ads also made sure to make it sound like all the refined and fashionable women were already doing it — or even better, requesting it — making the woman at home feel like she had to keep up with the Plastics. For example, this Gillette ad reads that the razor was finally created after "numerous requests from the leading summer and winter resorts and all the metropolitan fashion centers.” It hinted that the most stylish of women were already shaving, and if you wanted to join their ranks all you had to do was pick up a kit. Buying a razor wasn't just buying a product, it was buying a social distinction. A hairless woman was a superior woman.

Legs Were Put Into The Spotlight In The '20s And '30s

Now that women were on board with keeping their underarms smooth, Gillette wanted to up the ante and move that same urgency to the legs. After all, the more hair you had to shave, the faster your razors would dull and the more you'd have to buy.

But the ploy didn't really work. While the fashions in the 1920s flashed some shins and hemlines rose, stockings also came into style. "In the April 1929 edition of Harper’s Bazaar there were eight advertisements for eight varying brands of hosiery, while there was only one advertisement for leg hair removal. Although no such fashion existed for the problem of underarm hair, wearing stockings seemed to be a quick, hassle-free solution for leg hair," Hansen shared.

While there wasn't much you could do to hide wisps of hair when you threw up your arms in a Charleston, there was an easy way to hide your leg hairs. And seeing how shaving was messy and required a lot of upkeep, women didn't see the need to bother.

Pinups Changed The Shaving Game

The indifferent shoulder shrug towards unshaven legs began to change in the '40s, thanks to World War II. Or more specifically, thanks to the boys fighting overseas and taping up pinups to their bunkers.

Enter Betty Grable, her iconic white swimsuit, and her long, smooth legs. She sold over five million pictures throwing a smile over her shoulder and wearing nothing but a one piece and high heels — with those "million dollar legs" going on for miles. With that one image, "objectionable hair" suddenly applied to a lot more than a small patch of underarm. This was the opportunity advertisers and razor companies were waiting for: For years long hems and tights were women's excuses, but with pinup girls posing in short skirts, playful bathing suits and rompers, companies had their ticket in. Women wanted to emulate sex appeal, and they couldn't do it with hairy shins.

But sensuality wasn't the only reason smooth-shaved pinups inspired women to pay attention to their legs. It was also a way to show their patriotism. "What may have put the issue over the top was the famous WWII pinup of Betty Garble displaying her legendary and hairless legs; shaving one's legs became an act of pure patriotism," Renfroe explained. Much like with makeup and red lipstick at the time, being beautiful was seen as a duty to the country — to boost both the morale of the nation and the soldiers missing home. Makeup ads ran copy like "Keep Up Morale for National Defense” underneath their lipstick ads, and shaving was seen as the same civic duty.

War Rations Also Came Into Play

In addition to that, women no longer had the option of hiding their peach fuzz behind stockings thanks to rations. Nylon and silk were needed to create parachutes and war uniforms, and so women had to resort to wearing liquid stockings — pantyhose that were "thick, tinted lotions designed to create the illusion of fabric for women reluctant to appear bare legged." The thing was, though, the leg paint worked only if you had smooth legs. According to a woman's magazine at the time, "The best liquid stockings available will deceive no one unless the legs are smooth and free of hair or stubble. Leg makeup will mat or cake on the hairs and make detours round the stubble and give a streaky appearance," Herzig shares.

After awhile, though, more and more women decided that shaving and leaving their legs bare was simpler and far cheaper than bothering with any lotions or messy powders. This continued well into the postwar years, into a time where nylons were available again in department stores and drugstore aisles.

The women who adopted the habit in their teens and twenties passed it on to their daughters, and, according to Herzig, "By 1964, surveys indicated that 98 percent of all American women aged fifteen to forty-four were routinely shaving their legs."

And the rest is history. Mini skirts and mod shifts soon came after, bringing itty bitty bikinis trailing after them. And the more layers women were allowed to remove, the more hair that had to go with them. But at that point women didn't need any more ads to convince them to nick any stubble away — by then, we were well on board.

While the last couple of decades revolved around Brazilian waxes and no-hair-no-where looks, the last few years opened up a dialogue that brought us back to the 1800s, when body hair wasn't seen as so taboo. Embracing bikini lines and hairy pits, women are beginning to bring attention to the fact that shaving is just a social construct — a woman with hairy pits isn't unfeminine; that's just something we were taught to push products.

But whether you want to grow out your leg hair for the beach or wax it away smooth is entirely up to you — your body your rules. You can decide what's beautiful, and if it's a fuzzy leg, go for it. Gillette won't hold a grudge.

Images: Gaby Leg Make-Up (1); Nair (1); Zip (1); Gillette (3); Fox (1); Bustle