TV & Movies

Weighing Bridget Jones's Diary 20 Years On

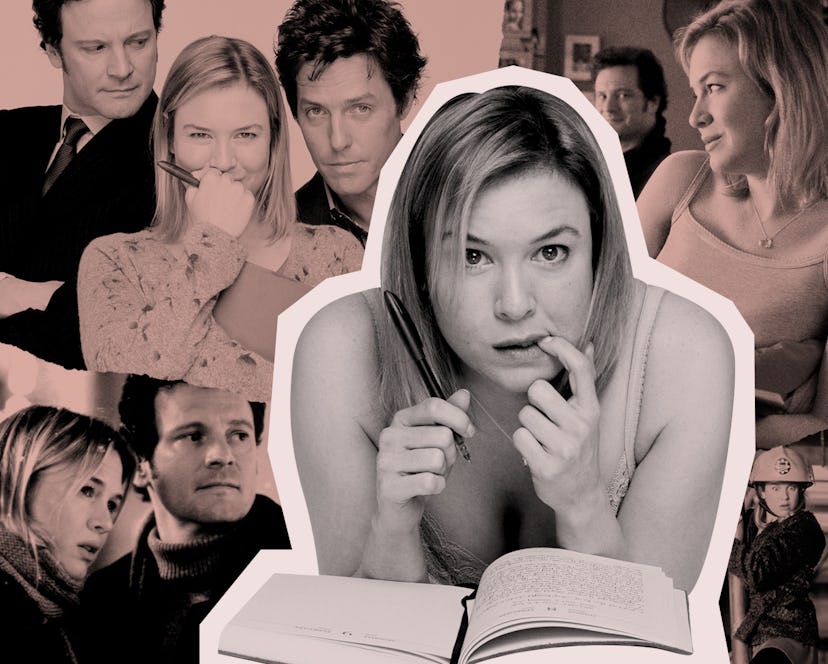

More honest and less glossy than its fellow 2001 release, Legally Blonde, the movie is still a feminist classic.

Twenty years ago, two films were released within months of each other, both featuring nearly identical sequences in which the film’s heroine dresses up as a Playboy bunny to attend a costume party only to arrive and discover — horror of horrors! — it wasn’t a costume party after all.

The two movies I’m referring to are, of course, Bridget Jones’s Diary and Legally Blonde, two rom-com masterpieces of the early ‘00s that share more in common than just two iterations of that same mortifying Playboy bunny scene. They both center on a woman who must come to the decision to cast off a bad man, even if he was once the object of her desires. Both heroines make the decision via peppy montage to devote themselves to building a new career, and both heroines are faced with the terrible moment of finding out in public that a boy they love is engaged to someone else. Both blondes have wildly supportive groups of friends, and though Elle Woods has more self-confidence than poor Bridget, both find themselves underestimated and determined to prove their detractors wrong.

But there is one key difference, at least when it comes to their legacy and the discourse surrounding them: the accessibility of their feminism.

I wish I could have been an Elle Woods, but I spent most of my young adult life as, well, a Bridget Jones.

It’s easy to explain why Legally Blonde is an underrated feminist text — a lesser movie could have turned Elle’s femininity or interest in fashion into a punchline; instead, Elle is celebrated for being smart and beautiful, and she wins by rejecting the stereotypically masculine qualities of competition and aggression in favor of communication, trust, and community-building.

But Bridget Jones, I’ve found through conversations with friends and acquaintances, is a little bit, well, pricklier. Personally, it’s one of my favorite romantic comedies, one that’s brutal and pitch-black in its humor while still delivering the feel-good fuzziness that any good rom-com should, but I understand why some might balk at characterizing it as feminist. After all, its heroine is obsessed with losing weight and finding a husband, two of the most stereotypical millstones of modern womanhood. And to make matters worse, Renee Zellweger’s negligible weight gain — from Hollywood actor to normal human woman — became a major story in the news cycle.

Ugh. Gah. Prickly.

Compared to Elle Woods, Bridget is prickly. She’s crueler than Elle Woods, both to herself and to others, and that self-loathing manifests in actively unhealthy decisions. But she’s also a protagonist that reminds me of me, or at least a version of me that I’ve been in my past. I wish I could have been an Elle Woods, a girl who always looked perfect and knew it but still treated everyone around her with kindness and acceptance, who made close female friends at every turn and saw herself as capable of achieving anything. I spent most of my young adult life as, well, a Bridget Jones: lusting after the wrong men and then falling in love with them, occasionally looking like an idiot at my job, fantasizing about a life where I weighed 20 pounds less while also using pints of ice cream to numb the mortifying ordeal of being a person.

Seeing someone imperfect but still able to pick herself up was, to me, always just as inspirational as Elle Woods’ victory in the courtroom at the end of Legally Blonde.

We live in a patriarchal world in which women are told that their weight reflects something about their personhood, and that failing to have a romantic partner will turn you into a spinster. These are actual concerns and fears that women in the real world deal with. Is a film anti-feminist, then, for accurately representing the sexist reality that exists? (It’s also worth considering that Bridget Jones is one of the few major hit franchise films of the past two decades to be directed by a woman, Sharon Maguire.)

I would argue that the core of Bridget Jones comes from Bridget being able to self-actualize and decide that she wants to make better decisions for herself, on her own terms — to empower herself with a new career, to support her father, to bond with her friends — and only then does she fall in love with a man who likes her... exactly as she is.

Seeing someone imperfect but still able to pick herself up was, to me, always just as inspirational as Elle Woods’ victory in the courtroom at the end of Legally Blonde. As a feminist message, it’s a little like Bridget herself: less glossy, more messy, but just as lovable.

Dana Schwartz is a writer of books, films, and television shows, including the upcoming Marvel series She-Hulk for Disney+. She is the host of the history podcast Noble Blood. Her next novel, ANATOMY: A LOVE STORY will be released February, 2022.