Books

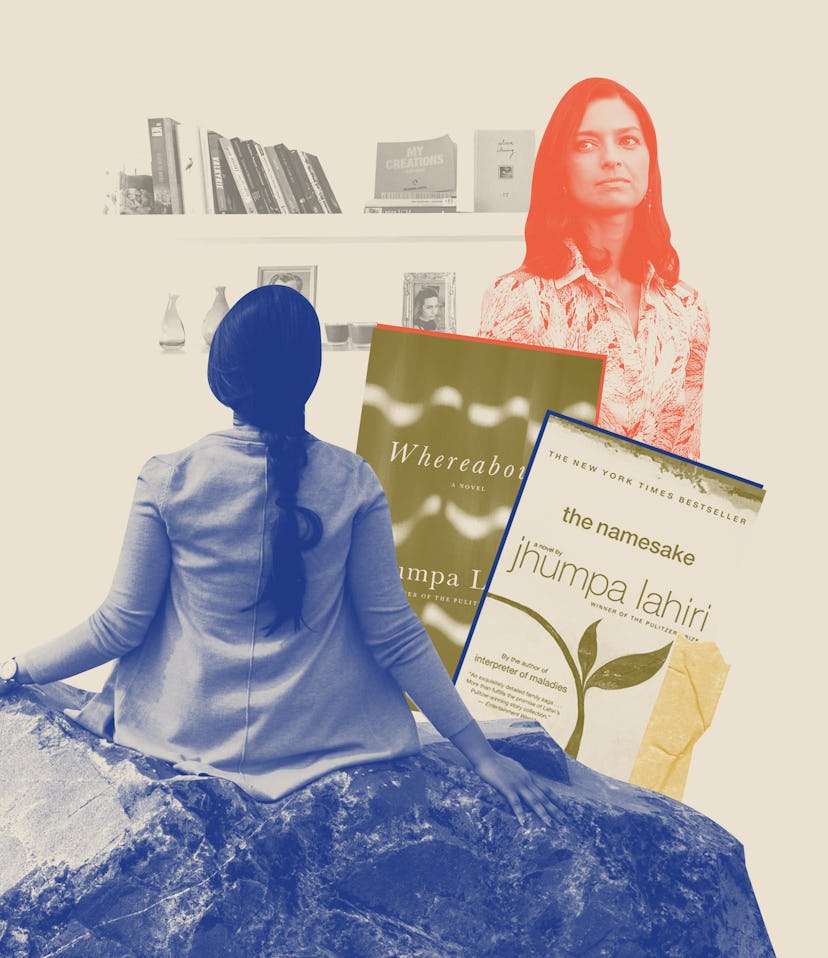

What Jhumpa Lahiri Taught Me About Feeling Like A Foreigner At Home

At every stage in my life, Lahiri’s writing has shown me something new.

My copy of The Namesake lives on my bookshelf in an easily accessible spot. Top right shelf, all the way to the left. Unless I point it out to you, you’ll probably miss it — wear and sun damage have left the text on the spine more or less illegible. Next to it are Jhumpa Lahiri’s other books, some in better condition, though my copy of Interpreter of Maladies is equally faded. I obtained both brand new at age 12, when I was fresh and bright-eyed. Time would break us both down, strip us of our varnish, leaving us at our most vulnerable. I find this to be an apt metaphor for Lahiri’s career.

The author’s latest book, Whereabouts, is a departure from her earlier writing. Her previous novels (The Namesake and The Lowland), story collections (Interpreter of Maladies and Unaccustomed Earth), memoir (In Other Words), and countless essays and uncollected works all focus on the experiences of Bengali or other South Asian people — more specifically, their displacement in white dominant spaces. But Whereabouts is a different novel, both in form and style; even calling it a novel feels wrong. Whereabouts reads as musings in brief vignettes or episodes, each no more than a few pages long. Identifying features, like name and setting, are omitted. We don’t know this narrator’s name or where she is (it’s heavily hinted that Whereabouts is set in Rome, though it’s never explicitly stated). By the end, we don’t even know where she’s going.

This shift has had polarizing effects on Lahiri’s critics and fans. Bengali writer Megha Majumdar, author of A Burning, has been drawn to Lahiri’s writing since Interpreter of Maladies’ release, which she read as a child in Kolkata. She is equally excited about this new direction. “Whereabouts is astoundingly, marvelously different from her novels that I've read before,” Majumdar tells Bustle. “In it I see a writer challenging herself, reaching for new artistic ambitions, new understandings of what the novel can be — and I find that immensely energizing.”

Others aren’t as enthusiastic. Though Whereabouts garnered generally positive reviews, some reveal qualms. “Blame Hemingway,” writes The Washington Post’s Ron Charles, alluding to Hemingway’s much-imitated model for meandering anti-plot, anti-frills novels. Madeleine Thein writes in The New York Times that reviewing Whereabouts “feels like an impossible task because the work is pared down to its essence, and arrives like a holding space for work to come.” These critiques aren’t new; Lahiri has long been chastised for veering out of her prescribed lane. In a 2017 interview with Lit Hub tied to the release of In Other Words, another digression in style and structure, she mentions that a number of trusted colleagues discouraged her from experimenting so publicly. But for Lahiri, writing is not necessarily meant for the reader — it’s a personal expression. And people change. There should be space allowed to do so.

I discovered Lahiri’s writing soon after The Namesake was published. It was recommended to me by my middle school librarian, a white woman who wore a lot of jewel tones and sometimes allowed me to sit with her in the library during lunch — and one of the few people who pronounced my name correctly. As a queer Iranian American in a mostly white community, I was also displaced, even though I was born and raised in Southern California. Both my queerness and Brownness contributed equally to my separation from others, so I turned to books as surrogates for the real connections I longed for. When my librarian friend handed me her own copy of The Namesake, she said I’d relate to it because it was also about Indian immigrants. I didn’t tell her I wasn’t Indian, but Iranian, or that I wasn’t an immigrant myself, but the child of immigrants. I wanted to tell her I was born in America, literally ten minutes away from my middle school, but instead I thanked her and tucked the book in my bag. I finished it in a few days and never returned it.

Maybe The Namesake was only recommended to me because my librarian, like so many others, thought Middle Eastern and South Asian people were a homogenous group, two sides of the same coin. This isn’t correct, but it’s not entirely wrong. After all, in white spaces, all they see is Brown. Identities aren’t exclusively self-generated; they’re constantly negotiated between the self and society, between self-perception and others’ perceptions. At times this can be gratifying, but mostly it’s just damaging. External expectations weigh down on our discernments of ourselves. I think that’s why I see so much of myself in Lahiri’s narratives.

I was too immature to fully understand how The Namesake spoke to a broader discourse of immigrants in America. Still, I related to the struggles of Gogol, a child of Begali immigrants living in America who doesn’t feel at home in either world he straddles. I had yet to read something that resonated with my own displacement in the place I was supposed to call home. Regardless if they were Indian or Iranian, it made me feel slightly less alone to know that characters like this existed. As underrepresented people, it’s almost unavoidable not to attach ourselves onto someone who resembles us, even if it’s not a perfect reflection. But Lahiri doesn’t write to tokenize this diaspora. Instead, her writing imparts the misgivings we have about ourselves, often felt by immigrants or those living abroad.

Lahiri chases change, chases inspiration. In 2011, Lahiri moved from Brooklyn to Rome. She had been lonely in America, where she’d lived for a large portion of her life, but Italy, in its vastness, felt like home. Immersing herself in the Italian language gave her more ownership of her identity; it wasn’t something passed down to her, like English or Bengali. She began writing earnestly in Italian, and for a while, only in Italian. This new vessel for creative expression proved to be more generative than anticipated. By 2015, her memoir In altre parole was released in Italy, and was translated to English — In Other Words — by Ann Goldstein. Soon after, her essay Il vestito dei libri was published in book form, translated by her husband Alberto Vourvoulias-Bush as The Clothing of Books. She wrote Dove mi trovo — the Italian version of Whereabouts — in spurts whenever she was back in Rome, now splitting her time between Rome and Princeton, New Jersey. As a result, reading Whereabouts feels like reading pages from her own diary. The comparison is inescapable: Lahiri’s identity is constantly in flux, and so her characters are, too. Through Whereabouts, Lahiri lets us know that one doesn’t always need to be an outsider to feel like one.

When I moved to New York City two years ago, I again read Interpreter of Maladies on the cross-country flight. Having spent 27 years in Southern California, my hometown that felt nothing like home, it was imperative that I leave in order to — excuse the cliché — “find myself”; like the myth of the goldfish, I felt that my growth was restricted by the confines of my environment. I was in search of new stimuli and inspirations. Had I not relocated, I would be emotionally and intellectually stunted. Likewise, had Lahiri not explored new emotional and intellectual territory, she, too, would be stunted. Lahiri has shown me that there isn't always a clear reason for change, or this relentless need to “find ourselves.” It just happens, and it should be celebrated. To chide Lahiri for this fluidity — the same reason that we salute her writing — seems sanctimonious. The need for change is a vital part of self-growth.

Whereabouts now sits on my shelf alongside Lahiri’s other books. This new copy will, too, erode in time. Its pages will yellow and tear, and the sheen of the book jacket will eventually lose its gloss. But regardless of its exterior corrosion, its words are evergreen. It’s how we interpret these words and internalize them within ourselves that alters through growth. Change is not abandonment. It’s a homecoming.